There are some who believe the only real evaluation is one that sums up an entire policy or program in a single number. I see genuine value in that number - but only if it’s used right. It isn’t objective, it isn’t precise, and it doesn’t count everything. It’s a piece of evidence, not a complete evaluation. My message to policy makers: if you must privilege this one form of evaluation over others, do it like this…

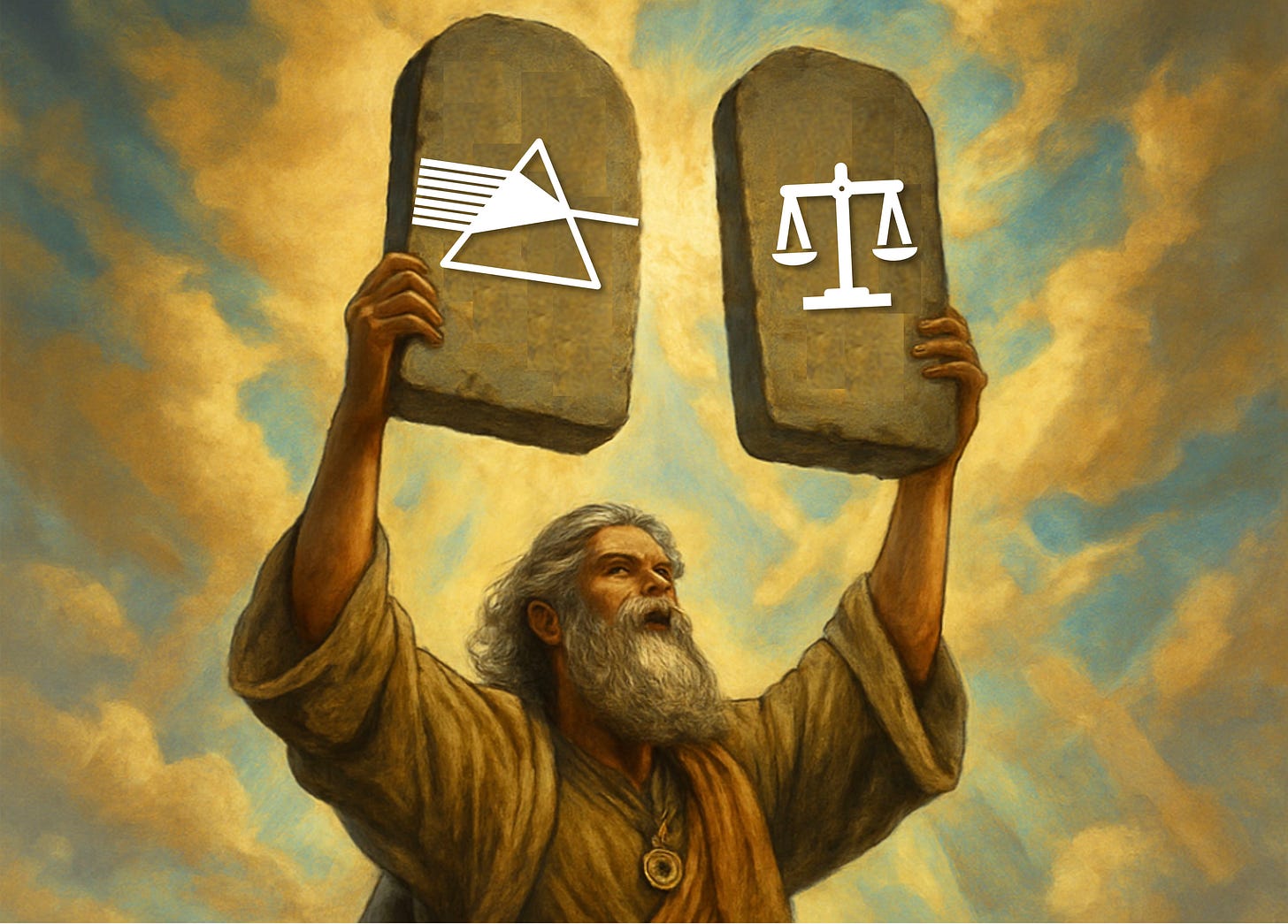

In an archeological breakthrough set to shake the foundations of social value analysis, Julian King emerged one foggy morning from the farthest reaches of the evalcave clutching a battered satchel. He thought his Indiana Jones hat looked cool, but most onlookers assumed he was Inspector Gadget.

He reached into the satchel and pulled out weathered stone tablets. Etched into these sacred slates were Ten Commandments for Good Social Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA) and Social Return on Investment (SROI). Did he find them, or did he make them? Nobody knows, but some say they were inscribed with divine impatience. Here’s what they said.

Also check out the new audio (AI podcast) version!

1. I don’t care what you call it, just do it well

Whether you’re doing a CBA or SROI, call it whatever you like, just do a good job. This often means drawing on complementary strengths of both traditions, like quantitative approaches from CBA guidance, stakeholder engagement and qualitative performance story from SROI. It also means following the remaining nine commandments…

2. Make a judgement

Spreadsheets don’t make judgements, people do. The number that a CBA or SROI produces - like a benefit-cost ratio - isn’t an evaluative judgement. It’s a piece of evidence. The judgement - the final conclusion from the analysis, like how worthwhile the intervention is overall - is a step beyond the number, and it depends on more than just the number. It requires additional evidence, together with explicit criteria, standards, and an inclusive deliberation process.

3. Reflect on what’s not in the ratio

Benefit-cost ratios don’t tell you everything. They’re estimates, not measures. They aren’t objective. They aren’t comprehensive. The costs and benefits included in the ratio can miss important aspects, such as context, distributional effects, qualitative and intangible factors. Value is more than money. Always reflect on what information isn’t in the ratio: which values, evidence, and nuances are omitted or under-represented, and how else they can be factored in.

4. Be transparent

Every analytic decision and its rationale, like what’s included and excluded from the ratio, how benefits and costs are attributed to the intervention, how they’re valued, how uncertainty is treated, how findings are interpreted, and more, should be open to scrutiny. Stakeholders and readers must be able to assess the quality of the study (using a checklist like this one), trace its logic, and replicate or challenge its conclusions. “Trust us, we’re experts” is never enough.

Ad break: 50% discount on full subscriptions until 31 July 2025. Access all articles on Evaluation and Value for Investment half price for as long as you want!

5. Engage stakeholders early and well

Understand what people value. Articulate the value proposition. Build the study around the experiences, values, and needs of those affected by the intervention. Include the voices of those impacted, especially those who are often overlooked. Use participatory, inclusive methods that surface diverse perspectives. Stakeholder input should inform study governance, design, conduct, interpretation and reporting of findings, ensuring contextual relevance and buy-in.

6. Be ethical

Evaluate with integrity. Balance technical credibility with care for how your analysis affects people’s lives. Recognise diverse values and cultural perspectives, and don’t assume one size fits all. Honour people’s lived experiences. Avoid doing harm - be guided by relevant program evaluation standards and ethical standards. Consider who may be disadvantaged, even when overall benefits seem positive. Be open to not using CBA or SROI, recognising no method should be preordained or imposed.

7. Make causality explicit

Don’t assume observed changes are attributable to the intervention. Substantiate whether there are credible causal links. Use rigorous approaches to investigate causal claims (there are loads of options for different contexts, e.g., theory-based evaluation, contribution analysis, difference-in-differences, regression discontinuity, etc). “Do Not Overclaim” is sensible advice but doesn’t replace causal inference.

8. Value what matters, and value it defensibly

Be clear where values come from (people). Understand where valuation data and assumptions come from, and how relevant they are. Consider how credibly different benefits and costs can be valued in monetary terms. Be conservative and realistic about what can reliably be monetised.

9. Address uncertainty and avoid false precision

Recognise that cost and benefit estimates are often imprecise and round them appropriately. Use sensitivity and scenario analysis to discover how varying assumptions affect conclusions. Communicate uncertainty openly. Range estimates and break-even analysis may be more honest than point estimates alone. Don’t assume benefit-cost ratios of different interventions are comparable.

10. Stop pretending it’s the whole evaluation

There are no gold standards, and no one method provides a complete answer to a value for money, social value, social impact, or social investment question. Mixed methods are essential for a nuanced understanding. Include as many evidence sources, criteria, and stakeholders as are necessary to reach valid, meaningful and fair conclusions. Evaluators know how.

Thanks for reading!

And thanks Charles Sullivan for helpful feedback on a draft. Errors and omissions are mine. Opinions are mine and don’t represent the people and organisations I work with.

Further reading

The eight social value principles: Similar to my ten commandments, the eight principles promote good practice. The principles are OK but in my view, they don’t push hard enough on critical reflection, methodological humility, causal inference, ethical responsibility, transparency, uncertainty, and evaluative judgement. https://www.socialvalueint.org/principles

Transparency in SROI and CBA: Estimating benefits and costs involves multiple analytic decisions that can affect results. Transparency about those decisions allows us to assess the quality of the study and whether it meets information needs. Lack of transparency erodes credibility. Here, I offer a checklist to help you assess the quality and transparency of your next SROI or CBA…

https://juliankingnz.substack.com/p/transparency-in-sroi-and-cba

Causal attribution in SROI: One of the eight social value principles is “Do Not Overclaim” the value attributed to an organisation’s activities. The problem is, this principle can be applied without addressing the more fundamental issue of whether the activities caused anything to happen at all…

https://juliankingnz.substack.com/p/causal-attribution-in-sroi

Beyond the Hierarchy: Sorry to break it to you, but there’s no hierarchy of VfM methods, and CBA isn’t top dog. Different methods contribute different insights. Here, I unpack a process for selecting a mix of methods that’s right for your evaluation...

CBA as a Mixer: I’m not the only one who argues CBA isn’t the whole evaluation. These rockstar professors from Oxford University, Duke University and the University of Chicago think so too…

Upcoming Value for Investment training workshops

Aotearoa New Zealand Evaluation Association (ANZEA), 6 & 13 August, online.

Australian Evaluation Society (AES): 16 September, Canberra. Limited places.

UK Evaluation Society (UKES), 24-25 September, online.

Private workshops can be scheduled for groups of 10-30.

Holy Moses! Did you download those files onto your tablet from the cloud?

I like you much better as Moses with the tablets and common sense rules than Debbie Downer with all the scolding about violence.

In the end it all comes to "Do unto others..."