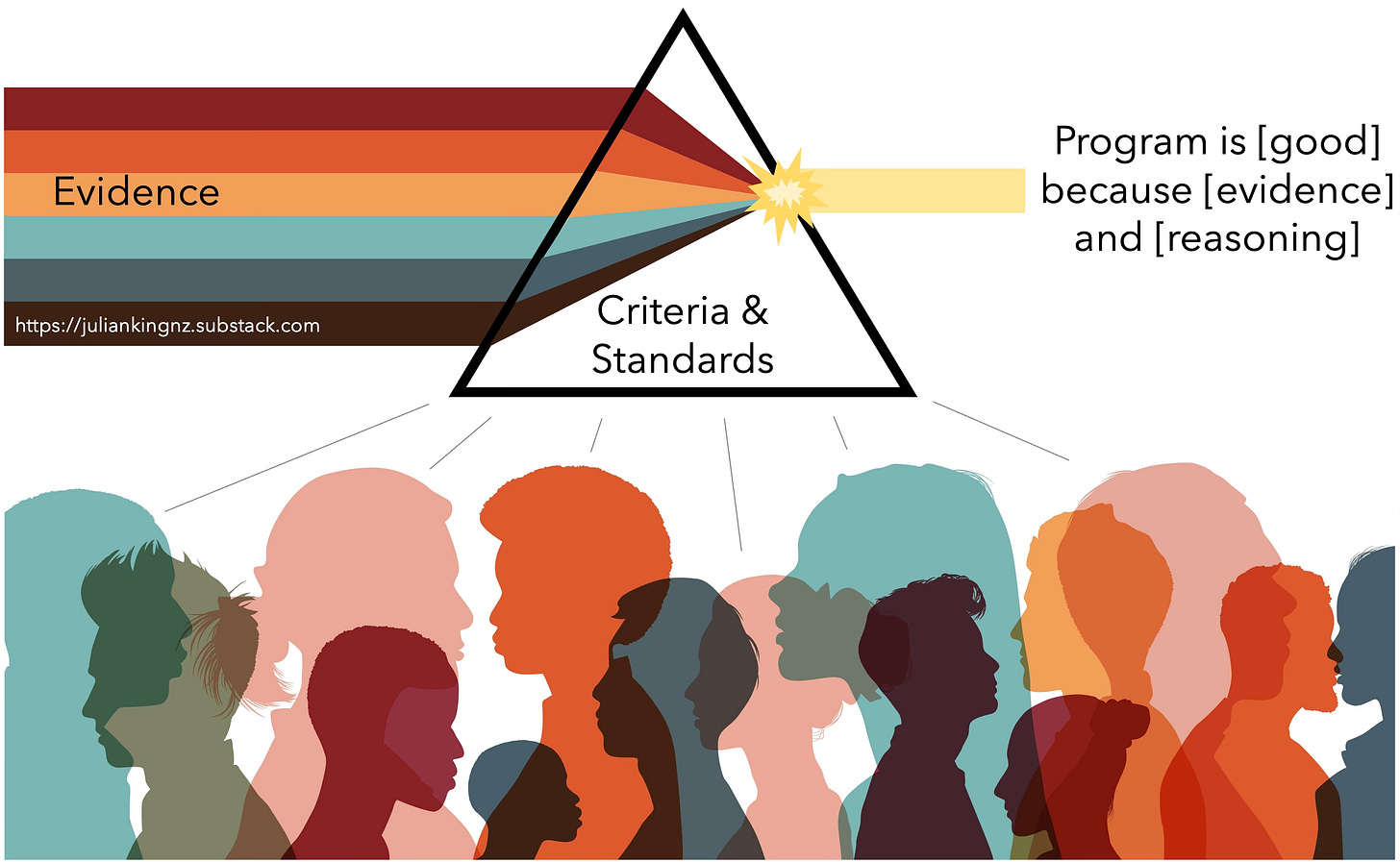

Criteria and standards: a logic, not a tool - and always there, whether explicit or not.

Evaluative reasoning is better when we throw sunlight on it.

Evaluative reasoning isn’t always visible - but it happens any time we judge the value of something. In professional evaluation involving value judgements by, with, or for people affected by policies and programs, conclusions are strengthened by making the reasoning explicit.

Evaluation (determining the value that people and groups place on something) is supported by a process called evaluative reasoning.

Evaluative reasoning isn’t a method or tool; it’s a logic that underpins evaluation and defines what it means to evaluate. It involves judging value, based on evidence and rationale.

The general logic underpinning evaluative judgements is that they’re based on:

Aspects of a policy, program, product (etc) that matter to people (“criteria”);

How good those aspects would have to be for people to consider them good enough (“standards”); and

Observations of the policy/ program/ product and its impacts (“evidence”).1

The criteria and standards are a bridge to get from the evidence to the value judgements - such as: how well a program is performing; whether it’s worth investing in; how it might be improved; and so on.

People might not know they’re using criteria and standards.

For example, they might simply be trusting their gut on the basis that they’ll know good value when they see it. But the criteria and standards are still there, hiding in the background. If a person is judging something to be ‘OK’, there’s a ‘because’ and it’ll be based implicitly on some aspects that feel important (criteria), and some notion of what ‘OK’ looks like (standards). Even if it’s a bit hard to put into words.

To illustrate: Why did Morris spend $100 on those shoes? Because they fit comfortably, they’re a quality brand, and the price was affordable. And he just likes them, OK?

Criteria: how they fit, perceived quality, price, overall appeal.

Corresponding standards: comfortable, brand, can afford, like.

That’s fine if you’re out shopping for shoes and nobody else’s opinion matters. Go for it Morris! Rock those shoes!

But when you’re a professional evaluator carrying the responsibility of evaluating a public or social investment that affects other people’s lives, trusting your gut isn’t enough.2 I’m not saying don’t listen to your gut (what Daniel Kahneman (2011) called “thinking fast”). I’m saying you need more than that alone. Evaluation with, or on behalf of others also requires “thinking slow” - deliberatively and logically.

Why does explicit evaluative reasoning matter?

Criteria and standards are always there, but they’re not always explicit. Making them explicit supports thinking slow.

Moreover, if you’re evaluating a policy or program, your conclusions will need to satisfy more than just yourself. You’ll need to be able to construct an argument that others will find valid and credible.

Showing your working

Making the criteria and standards explicit goes some way to helping with credibility, because people can trace how you got from the evidence to the judgement. It’s easier to accept a value judgement when the reasoning is transparent.

Nobody has to agree with your judgement. Transparent reasoning helps with this too, because people can point precisely to the parts of your argument that they disagree with. For example, perhaps they think a piece of evidence isn’t reliable. Or perhaps that particular aspects or levels of performance aren’t appropriately defined. Explicit criteria and standards make your judgements challengeable by throwing sunlight on the chain of reasoning.

Values come from people

Things don’t have value; people place value on things. Whose values matter when we’re evaluating an investment that affects people’s lives? Not mine. I’m just an evaluator. We’d better understand what matters to people affected by the investment and people who affect the investment.

It follows that we need to involve people in the evaluation. There are many different ways we could do this but the bottom line is that the definitions of what matters and what good looks like - the criteria and standards - need to come from the right people.3 When we elicit the values of stakeholders and make them explicit, those values become facts - based on empirical evidence and verifiable through systematic inquiry.

So now we have two necessary features of evaluative reasoning: criteria and standards should: 1) be explicit; and 2) represent the values of relevant people and groups. The former makes the reasoning traceable. The latter strengthens its validity. Both together enhance credibility and increase the likelihood that stakeholders will accept the conclusions.

A credible process

These two requirements (explicit criteria and standards, that represent what people value) are necessary, but not sufficient. We could, for example, meet these two requirements by collating evidence and bringing stakeholders together in a big room to judge how good the program is, constructing a narrative at the same time that specifies what aspects of performance matter and what level of performance would qualify as good.

But there would be two weaknesses with this approach. For starters, there’s a serious risk that we’ll bring the wrong evidence. Say, for example, we bring data about service accessibility, only to find the group decides that what really matters is acceptability to service users? It would have been better if we’d developed the criteria and standards first, to help guide us in collecting the right pieces of evidence.

The second problem is that everyone in the room is affected by, and/or affects the program. They have vested interests, at least perceived and probably real. For example, some stakeholders might be hoping the evaluation shows the program is effective so they can feel good about their self-worth, get more funding and keep their jobs. Others might be lobbying for changes to the program that they believe will help their families. And so on. So if we surface criteria and standards in real-time as part of making judgements, there is a possibility that the judgements will be swayed by vested interests - and even if we manage to run a clean process, just the potential for biases may still compromise the credibility of the evaluation.

Negotiating and documenting explicit criteria and standards in advance of the assessment guards against real or perceived fudging or moving the goalposts during judgement-making. It doesn’t provide a full innoculation against group biases (evaluators must remain vigilant to this), but it does provide some protection by surfacing and defining what matters to different people up front, and hence is a more credible process.4

So three key requirements are that the criteria and standards should: 1) be explicit; 2) represent the values of relevant people and groups; and 3) be defined in advance of the evaluation.5 There are more requirements but that’s enough for today.

How?

I recommend an 8-step process, working collaboratively with stakeholders to:

Understand the program, value proposition, who is affected, evaluation questions, and other relevant context

Define criteria for the evaluation: what aspects of value matter?

Set standards for the criteria: what does good look like?

Determine what evidence is needed and will be credible to address the criteria and standards

Gather the evidence, usually from multiple sources

Analyse the evidence

Synthesise the evidence through the lens of the criteria and standards to transparently judge how well the program is meeting its value proposition

Present clear answers supported by evidence and reasoning.

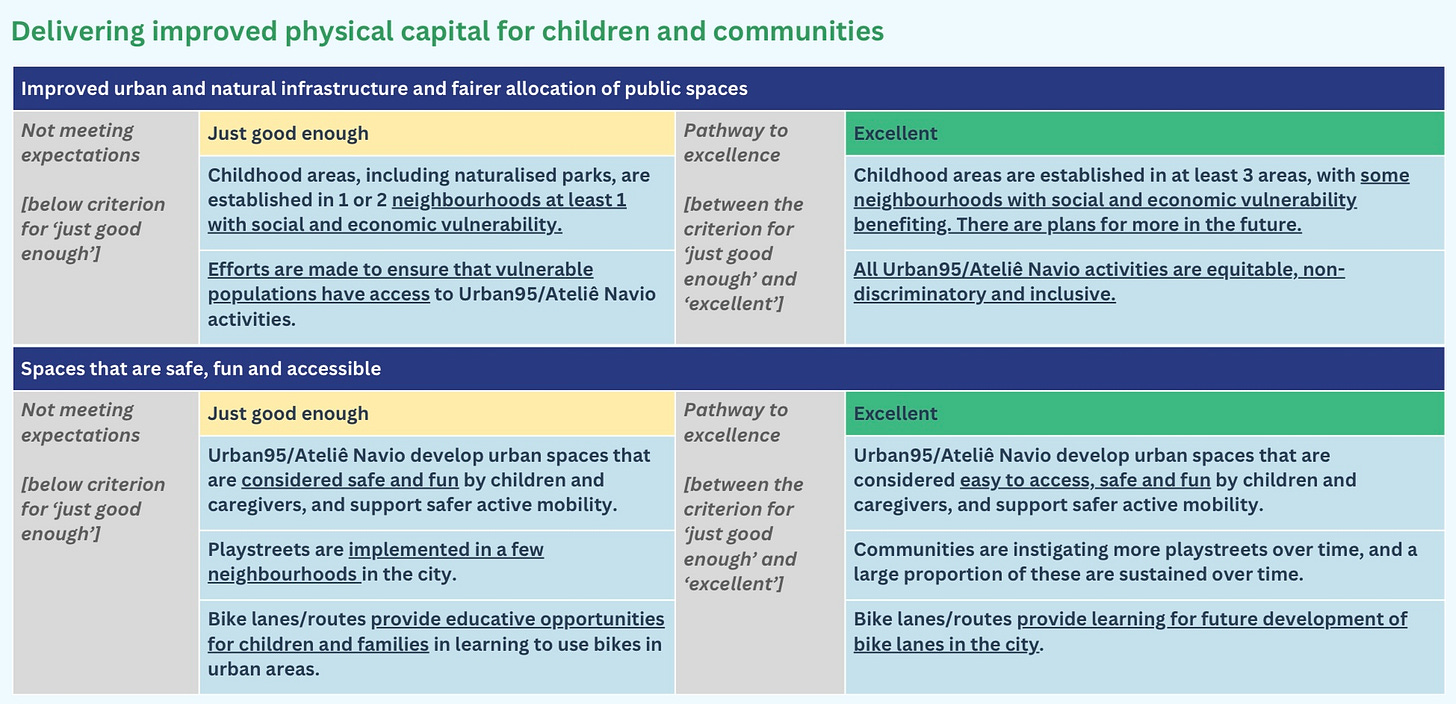

Rubrics - a tool to support inclusive evaluative reasoning.

Criteria and standards aren’t tools - they’re part of a logic. However, there are evaluation tools that help to make the logic explicit - like rubrics.

There are many ways to support explicit evaluative reasoning, and rubrics are one. A matrix of criteria and standards, wordsmithed with diverse stakeholders, represents an agreed, easily understood, revisable, systematic and transparent basis for making evaluative judgements. Creating a shared statement of values up front supports an evaluation that focuses on what is important to stakeholders and guards against individual subjectivity in evaluative conclusions.

Rubrics facilitate clear thinking throughout all eight steps of the process, ensuring the evaluation is aligned with the program and context (steps 1-3), collects and analyses the right evidence (steps 4-6), reaches warranted conclusions and communicates value on an agreed basis (steps 7-8).

Rubrics are more than technocratic tools - used properly, they help to democratise evaluation. More than a matrix of criteria and standards, a rubric is a strategy to help people reason clearly. Rubrics don’t make judgements - people do. To do a decent job of supporting people to make valid evaluative judgements, rubrics need to be co-created and used collaboratively by groups of relevant people. At their heart, rubrics support relational evaluation and power sharing.

What’s more, rubrics can be used to guide inclusive mixed reasoning processes that draw on both deliberative and tacit approaches to evaluation while keeping enough structure and focus to navigate systematically from hard questions to clear, well-justified answers. Rubrics support thinking fast and slow.

Bottom line

How you do your evaluative reasoning is up to you (see here and here for options). But if you’re evaluating something that affects other people’s lives, I recommend making it explicit and inclusive. Evaluative reasoning starts before, and finishes after evidence collection and analysis. It’s the bread and butter of our evalburger.

Evaluation is fallible - and making the reasoning explicit increases the likelihood that conclusions are warranted. The evidence, criteria, standards, their synthesis, and the process of making and communicating value judgements are susceptible to errors, biases, uncertainties, distortions, and injustices. Evaluation is about more than methods and conceptions of rigour - it’s also about ethics, power dynamics, relationships, and how arguments are structured. That’s why we need not only evaluative reasoning (the logic of judging value), but also evaluative thinking (careful scrutiny of each link in the chain to ensure our evaluations are sound).

Thanks for reading!

If you like this article, please hit the ❤️ button to increase its visibility on Substack.

Alternatively, you could present “just the facts” without judging value. But: a) that’s not evaluation, because like a Hawaiian burger without the pineapple, it misses the essential feature that would make it so; and b) it’s kicking the judgement can down the road because somebody, somewhere, like a politician or bureaucrat, will still make their own judgements, just as they were always gonna - and now they’re doing it without the benefit of knowing what matters to people. Not much fun for little Harpo.

But what about stakeholders’ tacit evaluations, like when they know in their bones that something is true? That’s data. Depending what it is that they know in their bones, it could be evidence about criteria (e.g., that stakeholders believe acceptability to service users is an important aspect of performance), standards (e.g., that they would consider it good enough if the majority of service users find the services acceptable), or performance (e.g., service users’ feedback on how acceptable the services are to them).

For example, we could ask, “What is the most important thing in the world today?” or “What is the most important thing in your life today?” (thanks to Mark Dalgety for these examples). Or we could ask “what is the most important thing about this program?” or “what would success look like to you?”. These kinds of questions get to the heart of people’s values and their answers can form the basis of explicit criteria and standards.

Different people value things differently. That variation in value perspectives is information. Evaluators have a duty to ascertain, understand, and report this information. When value perspectives conflict, we should help reconcile them, in keeping with program evaluation standards (Gargani & King, 2023).

In complex, emergent, fast-moving environments it can be more challenging to define criteria and standards in advance, as my colleague Kate McKegg pointed out. Nonetheless, in my view it is still possible and desirable to predetermine criteria and standards to a sensible degree of detail and specificity. The more fluid the situation, the less-detailed and less-specific the criteria and standards.

Enjoyed reading this.

It seems that it’s increasingly agreed upon that values are inevitable in evaluation — and unavoidably shape knowledge claims. What is important is understanding that values can influence this process and deciding what to do about it. If I’ve understood correctly, you are suggesting evaluators are responsible for (1) gathering multiple sources of evidence; and (2) making value judgments explicit.

What seems to matter is that the total body of evidence for evaluating a particular claim considers evidence for and against a claim from different relevant value perspectives. We need to understand how evidence is produced, what the evidence hides or emphasises, and better understand how we might consider alternatives. I suppose I’m wondering how criteria and standards alone, or which criteria and standards, can take us towards this?

Thanks Julian. Another great post, so clearly explained. So useful for sharing with newer evaluators and others we're work with.