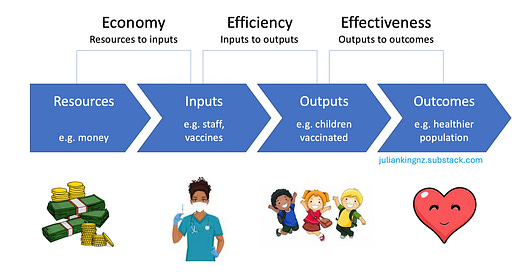

When it comes to assessing value for money (VfM), simple ratios like average cost per unit of output or outcome are appealing. These indicators are relevant to VfM and seem to promise “objectivity” and comparability. Sometimes they deliver. But to be useful they have to pass some hurdles for feasibility, quality and interpretability, without which they …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Evaluation and Value for Investment to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.