The way we naturally evaluate things in everyday life is often instinctive and immediate. We swipe right or left on dating apps, decide whether we like or dislike a meal after the first bite, or assess which watermelon at the market looks the ripest, all without much deliberation.

Professional evaluation, however, should be more conscious and systematic. It affects other people’s lives, influencing decisions about programs, policies, and resources. Because of this, evaluative judgements must be justified, i.e., they need to be warranted, backed by transparent reasoning and evidence. This is where Michael Scriven’s General Logic of Evaluation comes in, describing the process that guides us from observations to judgements. We can implement this logic by defining explicit criteria (aspects of value - what matters) and standards (levels of value - what good looks like), building a bridge from evidence to traceable, challengeable evaluative judgements.

In my opinion, this logic is descriptive, not prescriptive: it’s always there whether we know it or not. Making it explicit seems like a good idea to me. But there’s more to it than just using explicit criteria and standards. In my view (and many others, e.g., see Schwandt and Gates, 2021) this is a people-oriented process. Involving stakeholders (people who are affected by the program and those who affect the program) is an ethical imperative and strengthens the validity, credibility, utility and use of the evaluation.

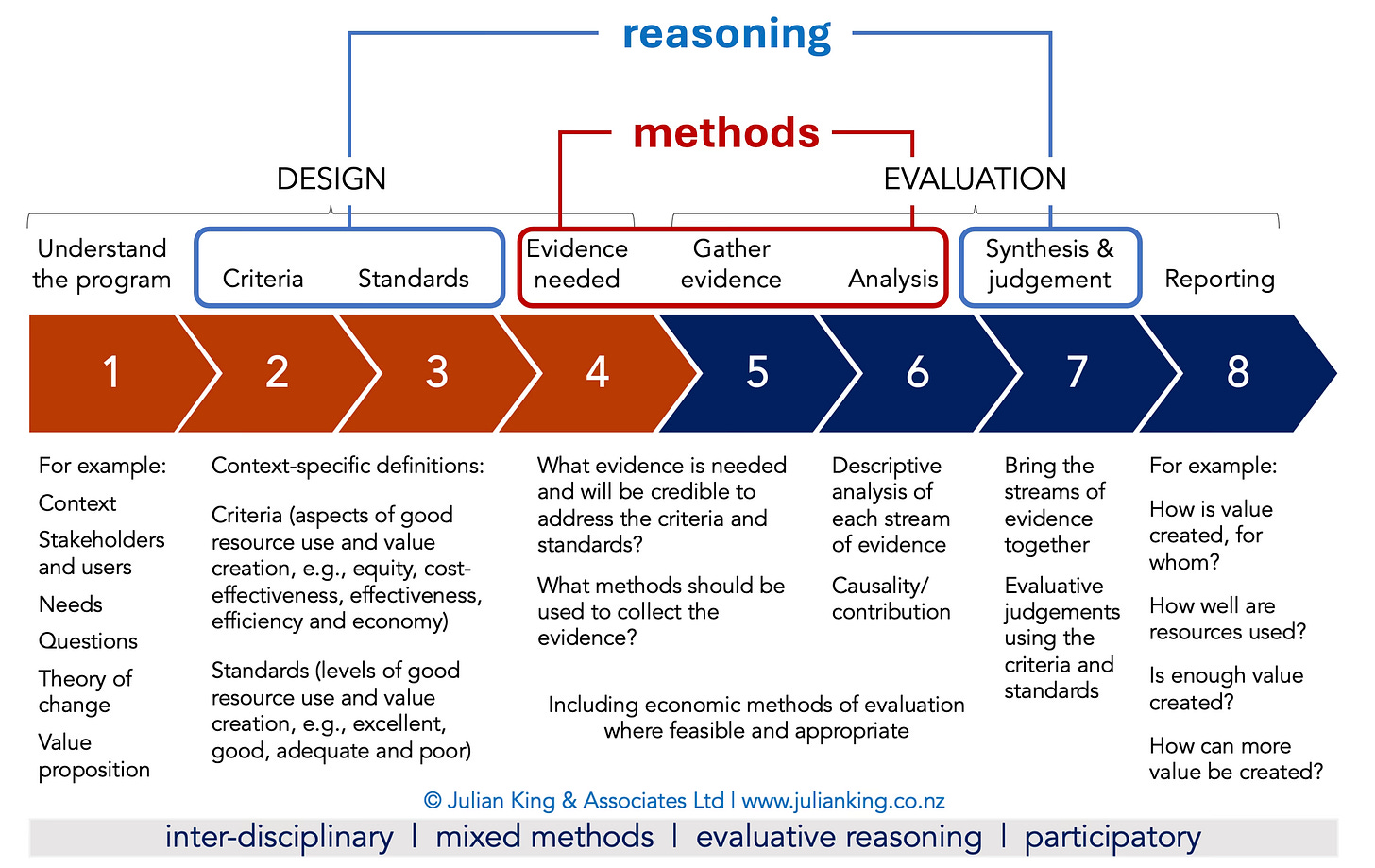

There are different ways of implementing the logic. I often use and teach the following stepped process because it helps to demystify the underlying logic, making it intuitive and practical. It distinguishes methods (how we gather reliable evidence - steps 4, 5, and 6) and reasoning (how we make explicit value judgements - steps 2, 3, and 7).

It’s designed to be inclusive, involving stakeholders at each step. It provides a road map for new evaluators, and a communication tool for salty old sea dog evaluators working with stakeholders who may be new to evaluation.

It’s a simplification of course, intended as a guide, not a straitjacket.

The reality of navigating an evaluation is more complex.

Research methods and evaluative reasoning, though neatly separated in the process above, are interconnected and interdependent. For example, facts are value-laden and values are facts, as I detailed in a previous article.

Values are facts: When defining criteria and standards, we discover and document evidence about what matters to people. In this process we can employ various research methods (from interviews and surveys to literature review, group deliberation and more), and facilitation tools (from rich pictures to card sorting) to gather and analyse evidence about values. In other words, through research and stakeholder negotiation we turn values into verified facts.

Facts are value-laden: They’re influenced by values and beliefs about (for example), what counts as credible evidence, how to collect, analyse and interpret evidence, how to navigate uncertainty (e.g., when evidence is ambiguous, contested, probabilistic, incomplete, etc). These (and related) matters deserve as much deliberation and negotiation as criteria and standards.

We can synthesise the (value-laden) evidence and (evidence-based) values in various different ways. Rubrics are one tool that can assist in this process, summarising criteria and standards in a user-friendly way. But there are no gold standards in evaluation and our selection of methods and tools ought to be determined contextually.

In practice, a good evaluation process may use multiple evaluative reasoning strategies.

I’ve previously unpacked different evaluative reasoning strategies here and here, using a taxonomy from Thomas Schwandt (2015), who identified four categories of approaches:

Technocratic approaches - systematically combining evidence and explicit values. For example, if-then statements, multi-criteria decision analysis, rubrics and, I argue, cost-benefit analysis belong in this category.

All-things-considered approaches - comparing and weighing reasons for and against an argument. For example, should a city introduce rent controls? Rationale for rent control may include protecting vulnerable groups from rapid rent hikes. Rationale against include potential negative impacts on the supply and quality of rental housing. An all-things considered judgement would account for both sides (and may consider alternatives to rent control) before arriving at a conclusion that acknowledges trade-offs.

Deliberative approaches - reaching a judgement through collective public reasoning - one example of which is the deliberative value formation (DVF) model that I outlined last week.

Tacit approaches - intuitive, holistic, based on “the vibe”. You know that feeling when your gut says “nope” and you get out as fast as you can? Tacit evaluation matters! In my opinion, we need more than gut feelings alone to justify evaluative conclusions, but we mustn’t discount the importance of tacit judgements. It’s a balancing act. Anthony Clairmont recently wrote about decisions in evaluation being like a nested set of Russian dolls, progressively revealing layers of rationale-for-rationale in a similar manner to the iterative questioning of the five whys. With the best will in the world, we can’t go on to infinity. At some point, several Russian dolls in, the warrant claim may be underpinned by a vibe.1 This doesn’t invalidate the importance of evidence and logical reasoning, but it reminds us of the complex interplay between intuition and analysis in human thinking. Some cultures are comfortable with tacit knowledge as evidence. In Western science, we like to hide it in a few dolls. Either way, it’s there.

I think that these different evaluative reasoning strategies should be used together.

For example, imagine we’re evaluating the quality and value of a program tackling a complex social issue. We begin by interviewing stakeholders to understand what they value. Insights from interviews shape a survey. The interviews and survey inform a draft rubric, which is negotiated and refined through stakeholder workshops and broader feedback. Through this mixed methods process, we turn values into facts, documenting them in structured criteria and standards.

The criteria and standards clarify the scope and focus of the evaluation. In collaboration with stakeholders, we consider what evidence is needed and will be credible to address the criteria and standards. We agree the appropriate mix of methods that will be used to gather and analyse the evidence. We gather, analyse and triangulate the evidence, identifying patterns such as general themes, outliers, and contradictions.

Then we facilitate a mixed reasoning process with stakeholders to judge the value of the program. We intentionally combine technocratic, deliberative, all-things-considered, and tacit approaches to evaluative reasoning, harnessing the strengths of different viewpoints to reach well-grounded, transparent judgements. For example:

Technocratic approaches for structure: We follow a systematic process, guided (but not bounded) by the rubric. We address the criteria one-by-one, with a view to determining the level of performance (standard) to which the evidence points for each criterion. Then we facilitate a process to reach an overarching conclusion against all of the criteria collectively.

Deliberative approaches for inclusive rigour: Throughout the process, we encourage open dialogue, debate, and collective reasoning that respects diverse perspectives while aiming for consensus or at least clearly articulated tensions and trade-offs.

All-things-considered approaches to weigh alternative judgements: There may be reasons for and against some evaluative judgements - for example, perhaps the program’s performance meets most expectations but fails on one or two important dimensions. Should we judge it to be good enough, or inadequate overall? Stakeholders compare these two potential judgements, assessing the relative importance of each dimension to reach an all-things-considered position.

Tacit approaches to underpin it all: We encourage participants to share personal or community experiences that provide valuable context and help to make sense of evidence. Using techniques like storytelling or iterative questioning (e.g., “why is this important?”), we uncover deeper layers of understanding until reaching a point where intuitive judgements can complement criterial reasoning. At the end of the process we encourage participants to consider whether the judgements reached feel right; if there’s a sense of discomfort about some aspect, we may take that as a signal to reopen it for further deliberation or to collect additional evidence.2

This scenario is illustrative. At the very least it’s worth knowing there are multiple evaluative reasoning strategies, and to consider the possibility that combining some of these strategies might help to strengthen the validity of evaluative judgements in a similar manner to which mixed methods can strengthen validity of evidence.

Bottom line

Explicit criteria and standards provide important structure for systematic, transparent evaluation and can be used in conjunction with multiple evaluative reasoning strategies. For example, the power of rubrics in transforming evaluation practice isn’t in the tool itself but how it’s used. I think the real magic is in the inclusive rigour of participatory, power-sharing approaches to making evaluative judgements. It’s not the rubrics, it’s the people and the conversations that happen around them.

Also see…

To illustrate: Why did you conduct this evaluation? To assess the effectiveness of our new employee training program. How did you define effectiveness? Meeting our organisational goals for employee development. How did you determine if it meets these goals? By comparing the program’s outcomes against predetermined criteria and performance standards. What makes these criteria and standards valid? They were developed with stakeholders and informed by industry good practices, academic research, and our organisation’s strategic objectives. Why are these sources considered authoritative? They represent a consensus of expert knowledge, empirical evidence, and align with our company’s mission and values. Yes, but why use a consensus between expert knowledge, empirical evidence and company stuff? 🤷♂️ Geez, leave me alone will ya, it just felt right…

The participatory approaches outlined in this scenario need not compromise the independence of the evaluation, if independence is sought. The rules of the game can stipulate that the evaluation team is responsible for making the final judgements. In this case, stakeholders’ judgements are an extra form of data that the team will deliberate on. However, not all evaluations require independent judgements. In some circumstances the whole point is empowering stakeholders to come to their own conclusions through a rigorous process - perhaps even to “develop value” as Schwandt & Gates (2021) suggested.

Very nice Julian, I particularly like how you talk about synthesising “…the (value-laden) evidence and (evidence-based) values in various different ways”, and that these ways can be technocratic, deliberative, all things considered, or tacit, or a combination of all. But the magic is in the “inclusive rigour of participatory, power-sharing approaches to making evaluative judgements”.