Value propositions: clearing the path from theory of change to rubrics

Being explicit about a program’s value proposition (like, to whom it is valuable and in what ways) can add depth to a theory of change and bring extra clarity to rubric development.

Today, Adrian Field and I presented at the Australian Evaluation Society (AES)’s international conference in Melbourne in a “Big Room session” - a 90-minute, audience engagement session in the large theatre with roving mics, where we developed a value proposition together in real time. Thanks to everyone who joined this session. In this article I’ll recap some key points.

Heads up! We’ll run a similar session at the Aotearoa New Zealand Evaluation Association (ANZEA) conference in Auckland in November.

The objective of this session was to introduce the idea of value propositions and to demonstrate:

Why they can be useful

That it doesn’t have to be hard.

Background

In our evaluation practice, we often use rubrics to transparently make evaluative judgements from multiple streams of evidence.

A rubric comprises a set of criteria (aspects of value) and standards (levels of value), co-created with stakeholders, articulating a shared set of values that are used as an agreed ‘prism’ to interpret multiple pieces of evidence and make warranted evaluative judgements.

A theory of change is often used as a key point of reference for identifying criteria.

But there’s a problem. It can feel like a conceptual leap getting from a theory of change to a set of value criteria.

This problem arises because change and value are different things.

Value can be defined as the merit, worth or significance that people and groups place on something. Among other things, people may place value on:

Impacts - real differences in people, places and things, caused by organisational actions;

Organisational actions - such as programs, policies, products, services, etc; and

Resources - monetary and non-monetary inputs.

In other words, people may place value on any element of a theory of change.

Impact and value are distinct concepts.

For example

Consider a Drug Treatment Court, a therapeutically-oriented alternative to imprisonment for people with addiction issues who are convicted of drug-related offences. Drug Courts provide community sentences and intensive support services, with rewards and sanctions to encourage rehabilitation.

Impacts (changes caused by a drug treatment court) could include graduates being in recovery from addiction, living lives free from crime, and reduced use of prisons.

Value (what matters, to whom) could include:

Graduates valuing increased wellbeing, optimism about the future, self-responsibility, self-respect, and personal growth

Families valuing improved relationships

Communities valuing improved safety

Treasury valuing cost reductions in healthcare, police, and corrections

And more.

This example illustrates a further important point: conceptually, impact and value are distinct, but in practical terms they are sometimes hard to separate. The impacts I mentioned above are impacts that people would (presumably) value. The value I mentioned above could be developed into impact measures.

Nonetheless, taking the time to explicitly consider value can often surface extra considerations that may not be visible in a theory of change.

We think theories of change should be explicit about value.

We find that when we carve out space to consider the question of value (like, to whom a program is valuable and in what ways) it can add layers of depth to a theory of change, which in turn helps us to develop clearer rubrics.

Defining value propositions can help to build a bridge between a theory of change, and a set of value criteria. A value proposition is a statement of intent that explains why something may be worth doing, and worth paying for, on the basis of the value it promises to add.

Exercise

We facilitated a group discussion with roving microphones to unpack the value proposition of the Ministry for Regulation, a newly established central agency of the New Zealand government aimed at “helping other government agencies to make their rules and regulations easier for New Zealanders to navigate”.

In my words (not the official language of the Ministry):

You know when your garage gets too full? From time to time we reach a point that we have too much stuff. We have to take everything out, decide what to keep and what to let go, and then put back the items we’re keeping in a more orderly fashion. Regulations are a bit like that too.

The Ministry for Regulation has been set up to ensure regulations deliver value to New Zealanders, by:

Improving regulatory impact assessments

Investigating ‘bad’ regulations in certain sectors

Developing regulatory skills across government.

The intended impacts of these organisational actions include:

Higher quality regulation

Greater transparency about the purpose, costs, benefits, and outcomes of regulations

Increased regulatory capability

Public trust and confidence in regulation and regulatory systems

Better economic, social and environmental outcomes.

That was the simplified logic model we shared for the exercise of co-creating a value proposition. For a more comprehensive look at the Ministry’s context and purpose, check out this article by Geoff Lewis and the Ministry’s own website.

Value proposition questions

Here are the questions we put to the group:

In a future article, we’ll unpack some themes from the conversation. For now, I’ll simply point out that the reason for asking these questions is that they help us to develop bespoke definitions for a common set of value-for-money criteria, called the Five Es (economy, efficiency, effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and equity) that collectively describe what it would look like for the Ministry to be a good steward of resources, deliver its outputs productively, achieve outcomes, create enough value and do so equitably.

We find that defining a value proposition makes it easier to identify context-specific aspects of good resource use and value creation than if we tried to connect a theory of change to generic definitions of the Es (e.g., efficiency: converting inputs to outputs). The value proposition questions encourage us to think more broadly about what critical factors influence value creation. More on that here.

Real examples

We shared some examples of real-world value propositions, like this one, developed by Prof Boyd Swinburn, Carolina Mejia Toro and colleagues, in collaboration with community and governmental stakeholders, for a free school lunches programme that delivers a lot more value than just full tummies, as you can see in the diagram. This value proposition helped the team and stakeholders to define meaningful criteria of good resource use as documented here.

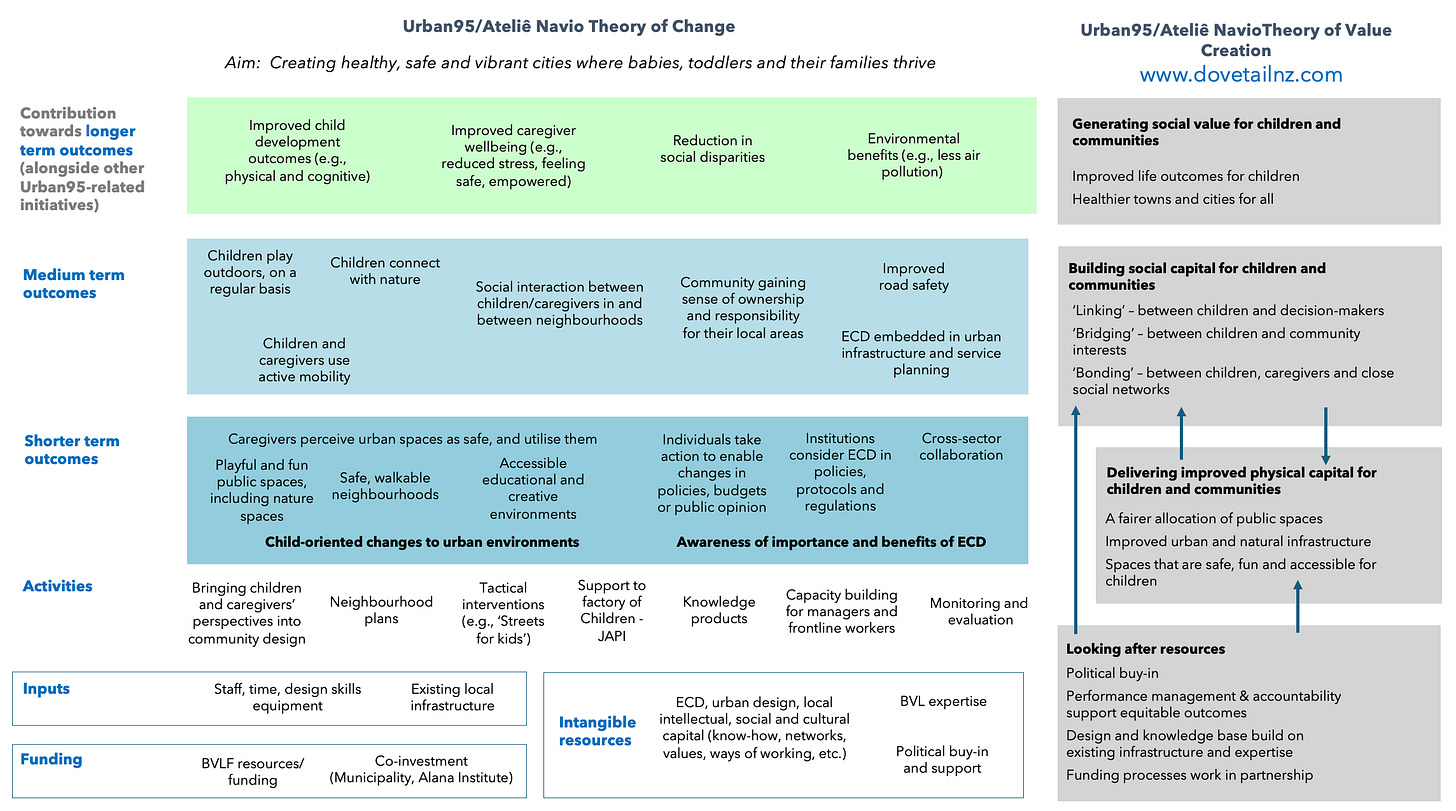

And we shared the following example of a program called Urban 95, which Dovetail Consulting and colleagues recently evaluated for the Van Leer Foundation, as you can check out here. In another presentation at the AES conference, Adrian and I described how we worked with program stakeholders, in two languages through a series of online workshops, to develop this theory of change and ‘theory of value creation’.

Urban 95 is an international initiative to transform cities for children and caregivers, prioritising the first five years of a child’s life and working city-wide with urban leaders, planners and designers. It asks: if you could experience the city from an elevation of 95cm (the height of a three year old), what would you do differently?

The ‘theory of value creation’ in the diagram below unpacks not only what kinds of value the program creates, but also how it creates value. It positions building physical and social capital as precursors to generating social value.

Reflection

Bottom line

Click through to part 2…

Where’s this?

If you’re the first person to correctly identify the location of this photo in the comments below, and tell me how you know, I’ll shout you a free 12-month subscription to the full Evaluation and Value for Investment archive.

This is in Maputo, Mozambique, residential and office towers. Found it using google images search