What's the value proposition of the Value for Investment approach?

What happens when we point the value proposition lens at the VfI approach itself?

There’s a perennial question in government spending: How do we know whether public investments create enough value? The Value for Investment (VfI) approach offers a fresh perspective. In this post, I unpack how VfI delivers value and why it matters.

I often talk about value propositions. But what exactly are they?

Put simply, a value proposition is a clear statement that explains how a product, service, program, policy, or organisation solves a problem, delivers value, and offers advantages over alternatives. It’s the compelling reason to invest, purchase, or endorse.

In evaluation, value propositions can help clarify what success looks like and why it matters, especially for public investments with complex outcomes.

The Value for Investment approach is built around this concept, framing policies and programs as investments in value propositions, and systematically evaluating how well those propositions are being met.1

In evaluation, we regularly assess others’ value propositions, but less often our own frameworks. So, what happens when VfI turns this lens on itself? What’s the value proposition of the Value for Investment approach?

VfI’s value proposition in a nutshell: better answers to value-for-money questions.

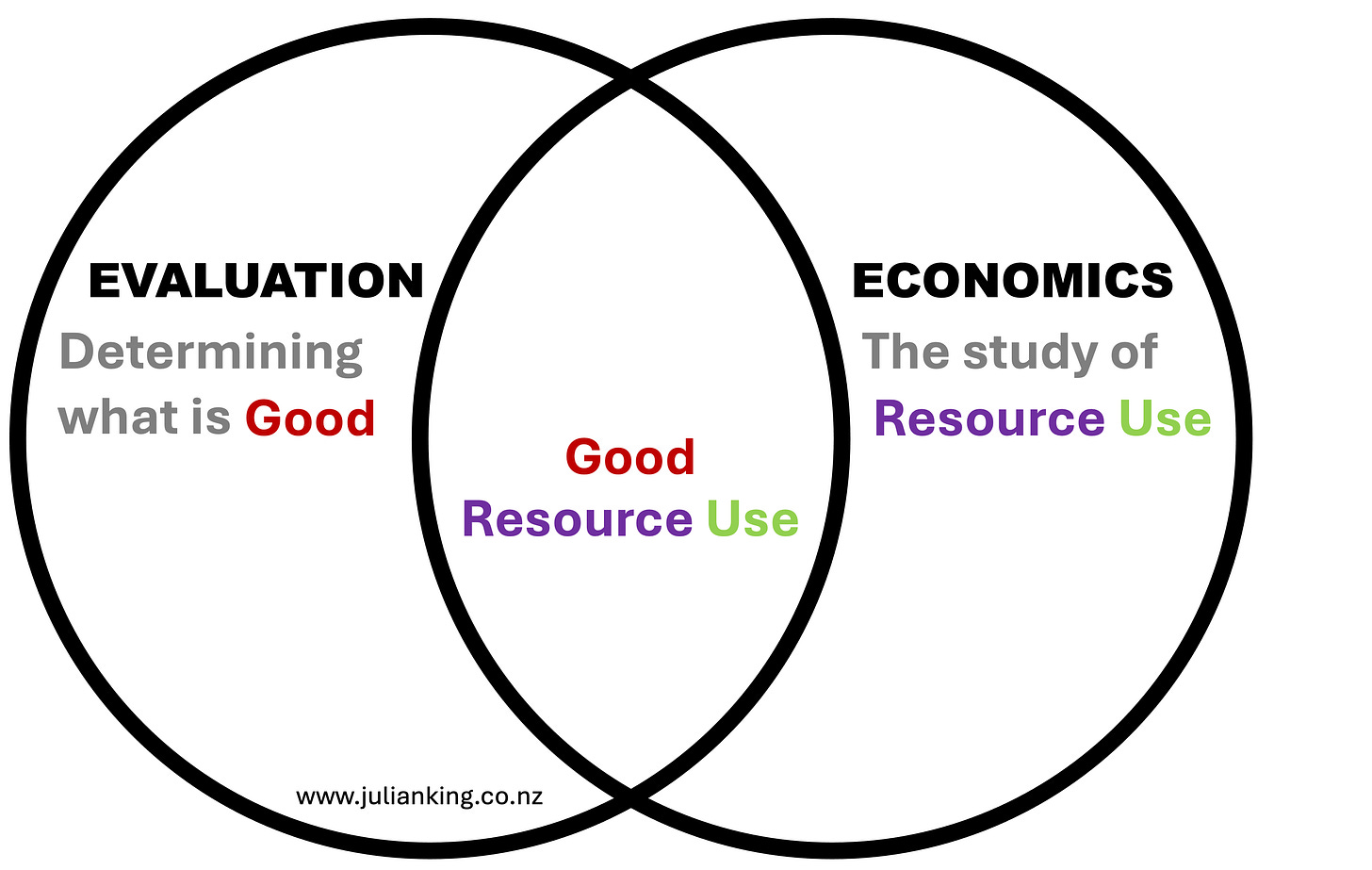

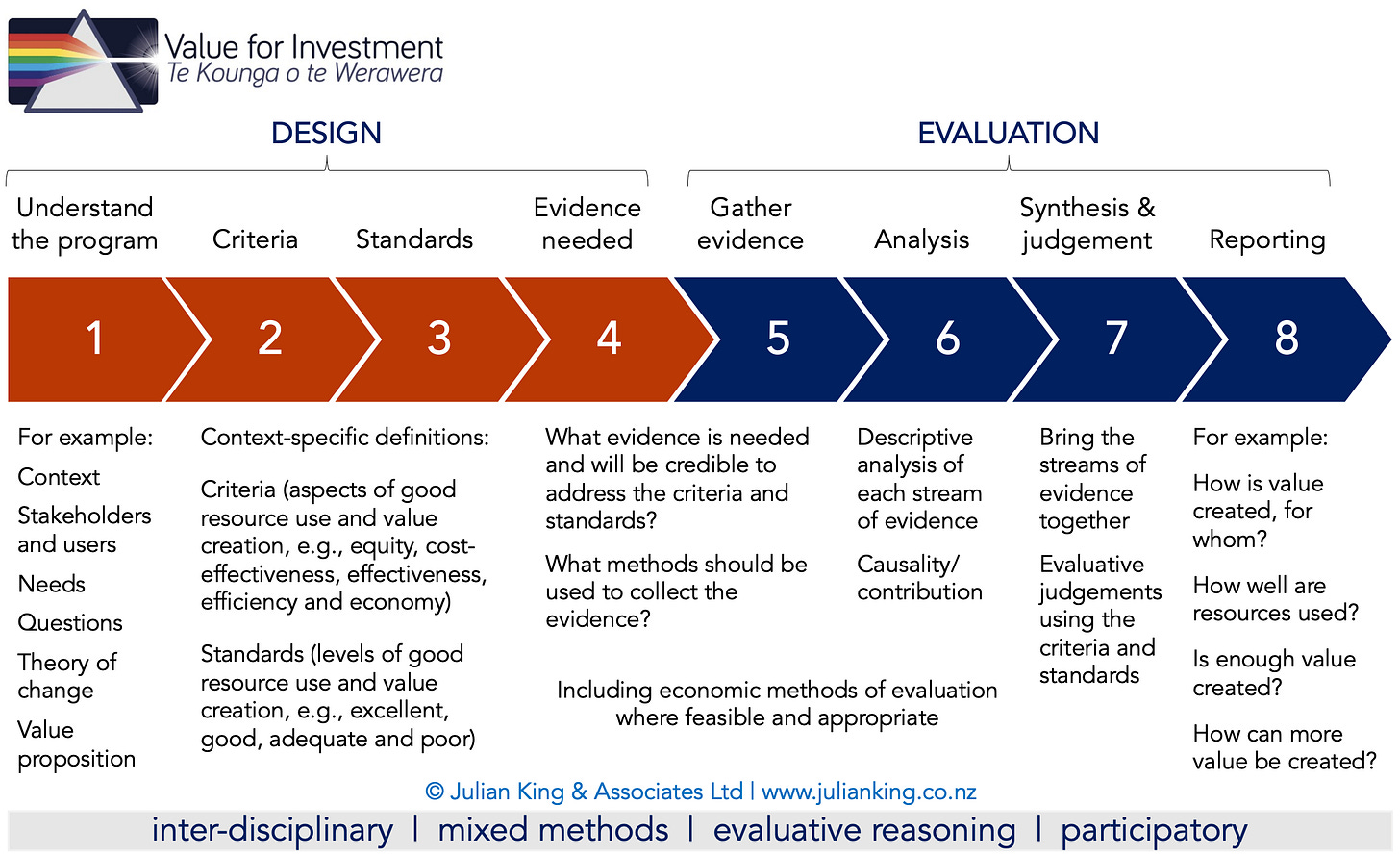

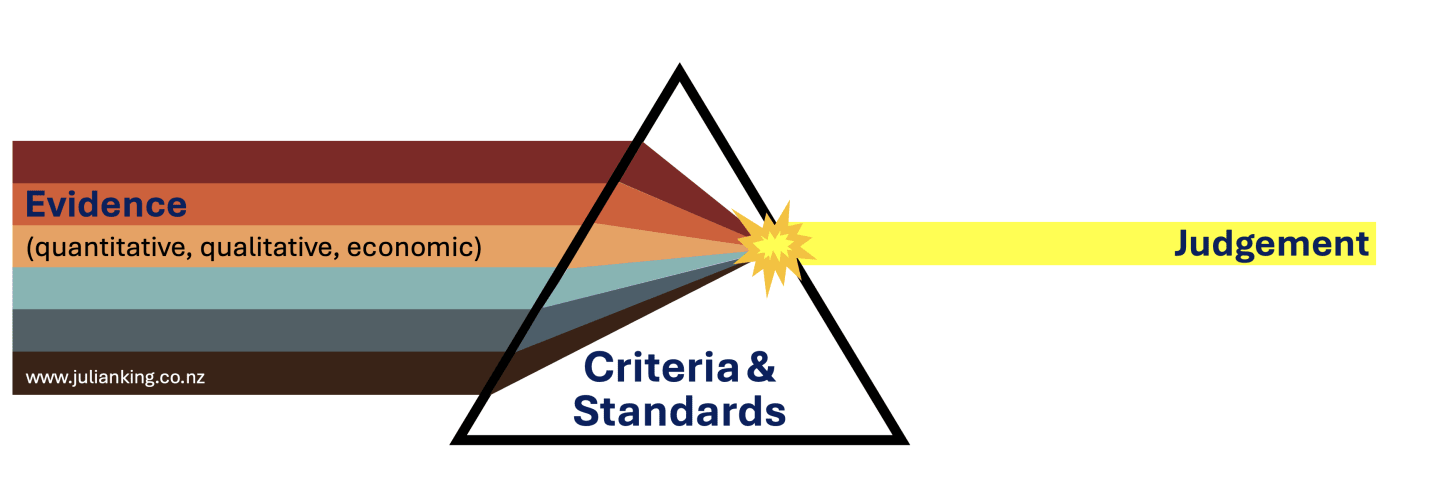

Value for Investment brings economic and evaluative thinking together to judge how well resources are used, whether sufficient value is created, and how more value can be created. It gives decision-makers the structure and reasoning needed to move from data to judgement. The result: better answers to value-for-money (VfM) questions.

That’s the short version. But value is rarely simple. Let’s unpack the VfI value proposition using the same series of questions it invites for any other investment...

To whom is VfI valuable, and how is it valuable to them?

VfI can deliver value to a wide range of organisations, decision-makers, communities, and evaluators:

Organisations that invest in public or social good: For public sector agencies, non-government organisations (NGOs), development organisations, and other funders, VfI strengthens resource allocation, accountability, learning and adaptation. It clarifies whether interventions deliver sufficient value for the resources invested, particularly in complex programs with social, cultural, or environmental dimensions. It also captures intangible aspects of value that are often not prominent in economic or indicator-based analyses.

Decision-makers, stakeholders and evaluation users: VfI supports informed, strategic and transparent decision-making. It encourages participatory evaluation design in which stakeholders contribute to framing questions, interpreting evidence, and judging value. Evaluators are prompted to “get off the fence” and provide clear, evidence-based value judgements that answer evaluation questions.

Communities: VfI brings local voices into defining what good value means in context, ensuring evaluations reflect lived experiences and values. Participatory approaches build trust, legitimacy, and shared ownership for those most affected by decisions.

Evaluators and others who conduct value-for-money assessments: VfI offers a structured, interdisciplinary framework for answering VfM questions. It guides evaluators through integrating multiple forms of evidence and making transparent, defensible judgements. Read on to find out how…

What are VfI’s points of difference?

VfI applies principles of good evaluation to VfM assessment. It brings clarity to a space often muddied by an interdisciplinary divide between evaluation and economics, siloed methods, narrowly focused metrics and opaque or missing value judgements. Its key features include:

Wrap-around & additionality: VfI isn’t another method, nor does it replace existing methods and tools. It provides a structured way of thinking to select, align, and combine appropriate methods and tools.

Bespoke evaluation design: VfI doesn’t prescribe criteria, methods, or metrics. Instead, it guides users to tailor these elements to the specific context, moving from a blank canvas to a contextually responsive evaluation.

Interdisciplinary thinking: Economics and evaluation are purposefully brought together, enabling richer assessments that draw on theory and practice from both disciplines.

Clarity and transparency: A VfI evaluation defines what good value looks like and uses those definitions to reach clear conclusions, opening the evidence and reasoning to scrutiny.

Framing as investment: Programs are assessed as investments in value propositions. Defining an explicit value proposition (in addition to a theory of change) is a precursor to the development of criteria and standards, which in turn guide decisions about methods, evaluative judgements and reporting. It can also uncover value creation mechanisms in ways that add insights to a theory of change.

Whole value chain: VfI defines value across the full intervention value chain - from resources to actions to impact - acknowledging that the value people and groups place on a program goes beyond just the intended results. It offers a more comprehensive view of how value is created, while clearly specifying what good resource use looks like.

A structured, flexible process: VfI’s stepwise framework provides a clear path for designing and implementing any evaluation - making it intuitive to learn, practical to use, and feasible to scale across whole organisations and sectors, while promoting flexibility for tailored design, reflective practice, and adaptation to emerging insights.

Engaging with complexity: VfI frameworks offer a practical and systematic way to grapple with the complexities of interventions and their contexts - including nuanced, intangible aspects of value that traditional VfM approaches may gloss over. Evaluators and stakeholders are encouraged to reflect on what constitutes public value, applying their own conceptual and methodological frames as suited to each situation, with VfI acting as a flexible guide rather than a rigid template. This space is evolving rapidly, with current PhD research shedding new light on leading practices. Stay tuned.

Support for learning and 360-degree accountability: VfI goes beyond accountability to funders, promoting wider accountability to stakeholders and communities. Integral to this, VfI facilitates active reflection, real-time learning, and adaptation.

Positive spin-offs for evaluative culture, skill sets and mind sets: Involving organisational leaders and stakeholders in VfI evaluations deepens understanding of evaluative reasoning, encourages mixed methods, and embeds inclusive rigour and participation. It expands perspectives on credible evidence and expertise, and strengthens ethical and social responsiveness. The result is a stronger evaluative culture, blending technical proficiency with broader aspects of good evaluation.

Versatility: VfI works across sectors - health, education, environment, social development, international development and beyond,2 to guide policy, organisation, portfolio and program reviews and funding decisions.

How could VfI contribute to a fairer, more ethical world?

VfI challenges and enriches conventional ways of judging public spending by broadening what counts as value and who gets to decide. Traditional VfM assessments often centre on technocratic approaches like cost-benefit analysis (CBA), or metrics organised around criteria set by funding organisations (e.g., the "5Es” of economy, efficiency, effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, equity). VfI invites a broader perspective:

Context-specific criteria: VfI requires evaluation criteria to be contextually grounded and responsive to the values of people affected by the investment. Even when using the 5Es, these criteria are redefined in program-specific terms that are meaningful to stakeholders. This often moves considerations like equity, ethics, and environment from the margins to the centre of the assessment.

Re-framing equity as core to public value: VfI recognises that many public investments exist because of inequities - addressing them is often their very purpose. This makes equity a central criterion for assessing value, especially in areas like health, education, housing, and social services. Framing success as “addressing inequities effectively, efficiently, and economically” shifts the focus from efficiency metrics to the core reasons for the investment.

Collaborative, ethical stakeholder involvement: Stakeholders are actively involved in defining value and interpreting results - enhancing validity, credibility, and evaluation use. By sharing power and engaging stakeholders, drawing on multiple perspectives, VfI helps democratise and legitimise what counts as value. This approach ensures resource use is judged ethically, with cultural and contextual appropriateness, and fosters social betterment.

Adaptable to support culturally led evaluations: Value for Investment also goes by the name Te Kounga o te Werawera, a Te Reo Māori (Māori language) name gifted to the approach and signifying its adaptation by Māori, for Māori, as Māori - where value propositions, criteria, standards, methods of engagement and what counts as credible evidence are governed by Māori values and worldviews. Similar work is underway to develop and test VfI frameworks led by the values of Pacific Island peoples. At last year’s AfrEA Conference, I shared a vision for Made-In-Africa VfM evaluation, with indigenous values at the centre of defining good resource use and value creation. The value of the VfI approach in culturally-led processes comes from its ability to be guided, adapted, and governed by those whose values and priorities lead the evaluation. This space continues to evolve, and its direction belongs with the communities it serves.

The intent is that VfI will help support resource allocation decisions that are not just efficient, but also meaningful, equitable and sustainable.

What real changes in people, groups, places, and things might VfI contribute to?

The success of VfI will be visible when real-world outcomes reflect its principles. Signs that VfI is making a difference include:

Uptake and application: Are evaluators and VfM assessors using the approach? Are organisations recognising its value? Are they adopting VfI at scale?

Clear evaluative judgements: Do VfI evaluations provide direct answers to evaluation questions? Are conclusions well-reasoned, evidenced, and transparent?

Use of findings: Are decision-makers using VfI evaluations to help make resource allocation decisions?

Adaptation and responsiveness: Is learning about good resource use leading to meaningful program improvements?

Effective resource use: Are we seeing better value from resource use, as a result of VfI-informed decisions?

Equity and fairness: Is VfI leading to inequities being addressed more efficiently and effectively? Are resources, organisational actions, and outcomes distributed more fairly?

Cultural relevance: Are assessments aligned with community values and priorities?

Stakeholder endorsement: Do those involved feel heard, respected, and well-served by VfI evaluations? Does their involvement in the VfI evaluation process enhance their understanding, ownership, and use of findings?

A stronger evaluative culture: Do leaders and stakeholders demonstrate greater understanding of evaluative reasoning, openness to mixed methods, and appreciation for inclusive, ethically responsive evaluation practice?

What ways of working will help to maximise VfI’s value?

Like any investment, VfI’s quality and value depend on how it is practised. VfI balances flexibility (accommodating diverse values, evidence, methods, and evaluator orientations) with fidelity (clear foundations). Each of the following principles is integral, and omitting any would compromise fidelity to the VfI approach:

Collaborative engagement and contextual sensitivity: Stakeholders, rights-holders and evaluation users should be involved throughout, from design and evidence collection to interpreting findings. The process and content must reflect local realities, values, and power dynamics, ensuring relevance and credibility to those affected. This approach fosters learning, mutual accountability, and deeper engagement, building shared understanding and ownership of results. However, its success depends on genuine stakeholder involvement, power-sharing and a willingness to act on diverse perspectives. The evaluation team is responsible for determining how this is done, to an appropriate depth and breadth for the situation. If stakeholders aren’t involved, it’s not a VfI evaluation.

Mixed methods: Multiple streams of evidence are purposefully integrated to get to the story behind the numbers, and the story beyond the numbers. Context-appropriate mixed methods strengthen validity through triangulation, drawing on complementary strengths of different approaches, and using iterative designs where one method informs another. Recognising the value of diverse types of evidence is essential (sometimes referred to as “qualitative and quantitative” but better understood as varying in multiple ways).3 Limiting the evidence to indicators, or privileging one method over others, misses the essence of VfI.

Inter-disciplinary: VfI brings together the lenses of evaluation and economics to judge the value of resource use.4 This is more than just mixed methods with a side-salad of cost-benefit analysis: evaluative and economic thinking should inform every step, helping to frame questions, value propositions, criteria and standards, evidence, and interpretation. Neither field alone can fully address VfI’s core questions about resource use and value creation; it is their intentional integration - drawing on complementary concepts, theories, models, methods and tools - that enables more comprehensive and credible conclusions. If you’re not blending evaluative and economic thinking, you’re not realising VfI’s full potential.

Explicit evaluative reasoning: ‘What matters’ (criteria) and ‘what good looks like’ (standards) must be clearly defined, making reasoning transparent. Criteria and standards are distinct from indicators and should be co-defined with stakeholders before choosing methods or metrics. Though this step requires up-front investment, it pays back in clarity and efficiency throughout the evaluation. Rubrics are an optional tool, but the logic of explicit criteria and standards is mandatory. Without evaluative reasoning, it isn’t VfI.

Mixed reasoning: Criteria and standards provide structure, but using them well is an inherently people-oriented practice. VfI involves multiple evaluative reasoning strategies, such as collective deliberation, weighing competing arguments, and drawing on tacit judgement, to arrive at balanced conclusions. Treating explicit criteria and standards as a technocratic tool misses VfI’s potential to support richer, more meaningful judgements.

Hard-nosed, honest evaluative judgements: VfI was developed to help evaluators and decision-makers reach warranted conclusions about whether and how investments deliver real value. Its purpose is good evaluation - not political manoeuvring, marketing, fundraising, or spin. VfI’s role is to help understand where real value exists, so decisions can create genuine public benefit. If you’ve already decided what you want the answer to be, before the evaluation has even started, please try someplace else.

Integration with wider monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL) activity: When a broader MEL effort is underway, VfI assessments should be embedded for conceptual coherence, practical coordination, and efficient use of evidence. Integrating VfI avoids duplication and inconsistent findings, helping teams align objectives and draw actionable conclusions. If there is broader MEL activity and VfI is not integrated, it is missing an essential aspect of good practice.

Clear reporting and transparency: Findings should be communicated directly and accessibly, with upfront answers to VfM questions and explanation of how conclusions were reached. This supports accountability and learning. Values, assumptions, and the philosophical and methodological underpinnings should be transparent. Limitations should be disclosed. Evidence should be clearly presented. The logic linking evidence to conclusions should be easy to follow. If the report doesn’t provide clear answers to VfM questions, or if readers have to do the heavy lifting to locate or make sense of the findings, it’s not VfI reporting.

As with any evaluation, VfI should be used in alignment with program evaluation standards and codes of ethics that apply in the local context, and guided by evaluative thinking.

What resources are invested in VfI, and what does good stewardship of those resources look like?

VfI assessments require multiple resources. You’ll need to invest time and attention to apply it well - but that’s time you’d likely be spending on evaluation anyway. VfI can help you get more value from resources such as:

Financial resources: Funding to support evaluation design, evidence collection, analysis, synthesis, and reporting. The costs of an evaluation should be proportionate to the significance, complexity, and scale of the decision at hand.

Human resources: Time, skill, and effort contributed by evaluators, program staff, and decision-makers. Good use of these people’s time requires clarity of purpose, and opportunities to meaningfully influence decisions.

Stakeholder input: Engaging those who are affected by or invested in the outcomes isn’t an optional extra - it's an ethical imperative. It’s central to defining what matters, what good looks like, and how trade-offs are understood. This requires appropriate processes, respect for the opportunity costs of people’s time (e.g., not overburdening them with poorly designed or low-value activity), and intentional effort to include diverse voices and ensure their input genuinely informs the evaluation.

Data and insight: VfI draws on a wide range of quantitative and qualitative information. Investing in high-quality, relevant, and appropriately interpreted data and analysis (including but not limited to causal inference) is essential to making warranted evaluative judgements.

Good stewardship of these resources includes:

Economical use of resources: Allocate evaluation resources appropriately, designing the assessment to be proportionate, timely, and useful for decision-making, and combining the skills of different team members based on the principle of comparative advantage.

Inclusivity: Ensure that an appropriate range of perspectives are represented, including those who are often marginalised or excluded from decision-making processes.

Ethics: Work with integrity, transparency, and respect for all participants, attending to power dynamics and the potential impacts of the assessment itself. If you involve AI tools, be responsible and accountable for what you put in and how you use what comes out.

The knowledge asset is free, and professional support is available

The VfI approach itself is the product of a substantial investment - developed through doctoral research and refined over a decade of real-world collaboration and testing. That investment of time, money, and effort has already been made, so others don’t have to start from scratch. Resources are freely available through www.julianking.co.nz.

VfI was created as a public good, intended to help everyone get better answers to VfM questions. Key collaborators, such as Oxford Policy Management, share this commitment, which is why we published our guide as an open-access resource.

For organisations seeking deeper engagement, VfI capability-building services are also available on a fee-for-service basis. These include tailored training workshops, presentations, advisory support, and peer review to help integrate the VfI approach effectively. Contact me for further information.

Conclusion

This post models the use of a series of questions to unpack a value proposition. It also articulates the value proposition of the VfI approach.

Articulating a value proposition is the foundation of an evaluation to address questions such as: What are we investing in? Who is it valuable to, and how? What inequities are addressed, at whose benefit and cost? Are resources well-managed, used productively, and having impacts? And how well is the investment meeting its value proposition, across all dimensions that matter?

VfI’s value proposition is to help find better answers to one of the hardest questions in public investment: Are we creating enough value, and how can we create more?

When used with fidelity and flexibility, VfI is more than just a framework - it’s a way of working that helps make public spending more transparent, inclusive, and meaningful.

For open-access guidance, examples, training opportunities and more, check out the VfI portal at www.julianking.co.nz.

What is VfI’s value proposition to you?

Did I capture it above? Did I miss anything? What resonates with you? Let me know!

Acknowledgement

Thanks to Dr Adrian Field, Co-Director of Dovetail Consulting and an experienced leader of VfI evaluations, for peer review of this article. Any errors or omissions remain my responsibility. This post reflects my professional opinion and not those of the organisations or individuals I work with.

When a decision-maker allocates resources to a program, they are investing in “a proposition about the value of a course of action”, as Andrew Hawkins put it. Value propositions are useful constructs because if we can define them, we can evaluate how well they’re met. In business, a value proposition is a declaration of intent that communicates the benefits of a product or service to customers. I think social programs should have clear value propositions too. In social programs there is extra complexity, because the customers who receive the service and the customers paying for them are different groups, so questions of “value to/from whom?” and “who decides?” are critically important.

Examples of sectors where VfI has been used include aged care, agriculture, climate, community services, conservation, creative arts, disability, disaster risk management, early childhood development, economic development, education & training, emergency preparedness & response, energy, environment, female economic empowerment, financial inclusion, governance, health care, housing, humanitarian assistance, indigenous development, insurance, international aid & development, justice, labour force, law enforcement, local government, market development, mental health & addictions, nutrition, philanthropy, public financial management, research & development, science, social development, social impact, sport & recreation, trade & enterprise, transport, urban design, women’s rights & health.

For example, the mix of methods potentially includes primary data collection and evidence from secondary sources. It can include ‘objective’ data (in the sense that it can be independently observed) and ‘subjective’ data (in the sense that it relates to participants’ self-reported experiences). It can include inter-objective evidence (pertaining to complex systems, networks, technology, government, natural environment) and inter-subjective evidence (e.g., shared experiences, collective values, meanings, language, relationships, cultures). Depending on the situation, it could include any mix of quantitative and/or qualitative data, which could be gathered through observation, surveys, focus groups, interviews, administrative databases, financial accounts, literature, documentation, and more. And, of course, multiple approaches to causal inference. VfI doesn’t limit these possibilities - it opens them up to methodological pluralism, bricolage, and Cubist evaluation.

Combining the two disciplines of evaluation and economics is part of VfI’s minimum specification - but it doesn’t have to stop at two disciplines. Depending on the context, other disciplines may well be involved. For example, when evaluating mental health and addiction interventions, the discipline of psychology may also be important. When working in specific cultural contexts, VfI should be led by appropriate cultural values and priorities.