Surfacing values through rubric development

Why & how

Welcome to new readers, who may be attending my upcoming Evaluation and Value for Investment (VfI) training workshops and presentations in London, in association with Verian Group. This post is pre-workshop reading, and includes links to VfI guidance documents. If you’re a long-term subscriber to my Substack, the opening paragraphs will fly over familiar territory before landing on some new rubric development facilitation tips.

Evaluation involves making judgements.

Evaluation, as Michael Scriven said, involves systematically determining merit and worth - or, as E. Jane Davidson put it, how good something is and whether it’s good enough. Answering a “how good” question takes more than evidence:

Evaluation is a judgment-oriented practice – it does not aim simply to describe some state of affairs but to offer a considered and reasoned judgment about the value of that state of affairs (Schwandt, 2015, p. 47).

There’s a logic to making evaluative judgements.

According to the General Logic of Evaluation, evaluative judgements flow from:

Evidence (independent observations of performance)

Criteria (defined aspects of value) and

Standards (defined levels of value).

Interpreting evidence through the prism of criteria and standards is called evaluative reasoning. It isn’t a method or tool - it’s a logic that underpins evaluation.

Rubrics implement the logic of evaluation.

Rubrics, introduced into the field of evaluation by E. Jane Davidson, are one way of specifying criteria and standards, with descriptors of what the evidence would look like at the intersection of each criterion and standard. Rubrics give us an intuitive basis for judging the value of a policy or program. There are different ways of structuring rubrics; the following illustration is one example.

Rubrics help to make evaluative reasoning explicit.

Evaluative reasoning isn’t always visible, but it happens any time we judge the value of something (even as a leisure activity). In professional evaluation, involving value judgements by, with, or for people affected by policies and programs, conclusions are strengthened by showing our working (being transparent about how we got from the evidence to a judgment). Rubrics help to provide the needed transparency.

Rubrics are a centrepiece for stakeholder engagement.

Things don’t have value - people place value on things. Criteria and standards help people to place value on things, by describing what aspects of value matter to people, and what good value looks like. Which people? As evaluators, part of our job is to facilitate a process to surface the values of those who impact or are impacted by a program, such as its architects, funders, providers, and communities. Co-creating rubrics brings stakeholders to the table to define what ‘good’ looks like for a specific intervention and context.

Involving stakeholders is an ethical imperative in rubric development.

Collaboratively developing rubrics surfaces stakeholders’ values, helps different stakeholders to experience and understand the diversity of perspectives involved, and guards against the evaluation only reflecting the values and assumptions of commissioners and evaluators.

When we start to consider the values of different stakeholders, it becomes clear that evaluation is inextricably bound to issues of power - whose values count, what counts as credible evidence, who gets to have a voice, who decides. Participatory, power-sharing evaluation becomes something we see as essential, not optional.

Involving stakeholders in rubric development pays back.

Rubrics help ensure a valid evaluation design. Rubric development engages stakeholders in defining what matters to them. Often this is their first opportunity to discuss the program’s value explicitly, which is crucial for both program design and evaluation. These discussions ground the evaluation in the program’s context, ensuring a focus on relevant aspects of quality and value.

Rubrics pay back in clarity throughout the evaluation process by guiding decisions about evidence needs, method selection, tool design, organising evidence, making evaluative judgements, and structuring a report. At each step, this clarity enhances the efficiency and quality of the evaluation.

Co-developing rubrics supports utilisation-focused evaluation by helping stakeholders to gain a deeper understanding and experience of evaluation. This makes it more likely that the evaluation processes and products will be understood, endorsed and used.

Co-creating rubrics is a team sport.

As we reflected in our open access Value for Investment guide for health and community services:

Developing rubrics is an art and a science, requiring skills in facilitation, cultural competence and knowledge, robust conceptual thinking, wordsmithing, and graphic design. Having the right mix of skills on the team and the right mix of stakeholder perspectives in the room are paramount (King, Crocket, & Field, 2023).

Tips and tricks for developing rubrics with stakeholders

The basic steps in rubric development are:

Bring the right people together, considering who needs to be involved for evaluation validity, credibility, utility, and who has a right to a voice.

Understand the program. Do your homework on the program and its context, working with stakeholders to create a shared language about what the program is, what it does, and the value it sets out to create.

Define the aspects of performance, success, quality, or value that matter. These are the criteria. Examples include relevance, efficiency, equity, sustainability, accessibility, etc. Crucially, this includes defining what they mean in the context of your program.

Define levels of performance. These are the standards. Examples are excellent, good, adequate, and poor; or excelling, embedding, evolving and emerging.

Define what each criterion would look like at each level of performance.

This approach is flexible and needs to be tailored to context. While this flexibility is a strength of the approach, it also makes it hard to generalise about how rubrics should be developed. Therefore, the following tips are guidelines, not rules. Some of these tips are new and some are adapted from Assessing Value for Money: The Oxford Policy Management Approach.

Bring the right people together

Who needs to be involved? Jane Davidson offers the following considerations:

Validity: Whose expertise do we need? Examples include people with expertise in evaluation, subject matter knowledge, and familiarity with the local context and culture.

Credibility: Who needs to be involved to ensure the findings are trustworthy and believable to stakeholders?

Utility: Who will use the evaluation findings? Including primary users can increase their understanding and commitment to the results.

Voice: Who has a right to participate? Especially consider groups historically excluded from evaluations, such as indigenous peoples.

Cost: Bearing in mind the opportunity costs of taking people away from their other work, what’s a feasible and proportionate approach to engagement and when should different stakeholders be involved for maximum benefit?

Who to involve and how to involve them is a balancing act. People may be involved in different ways and to different levels of depth. For example, there may be a small “coalition of the willing” who contribute in depth to co-creating rubrics, a wider stakeholder group who have the opportunity to review a draft and provide feedback, and others who are kept informed but don’t directly influence rubric development.

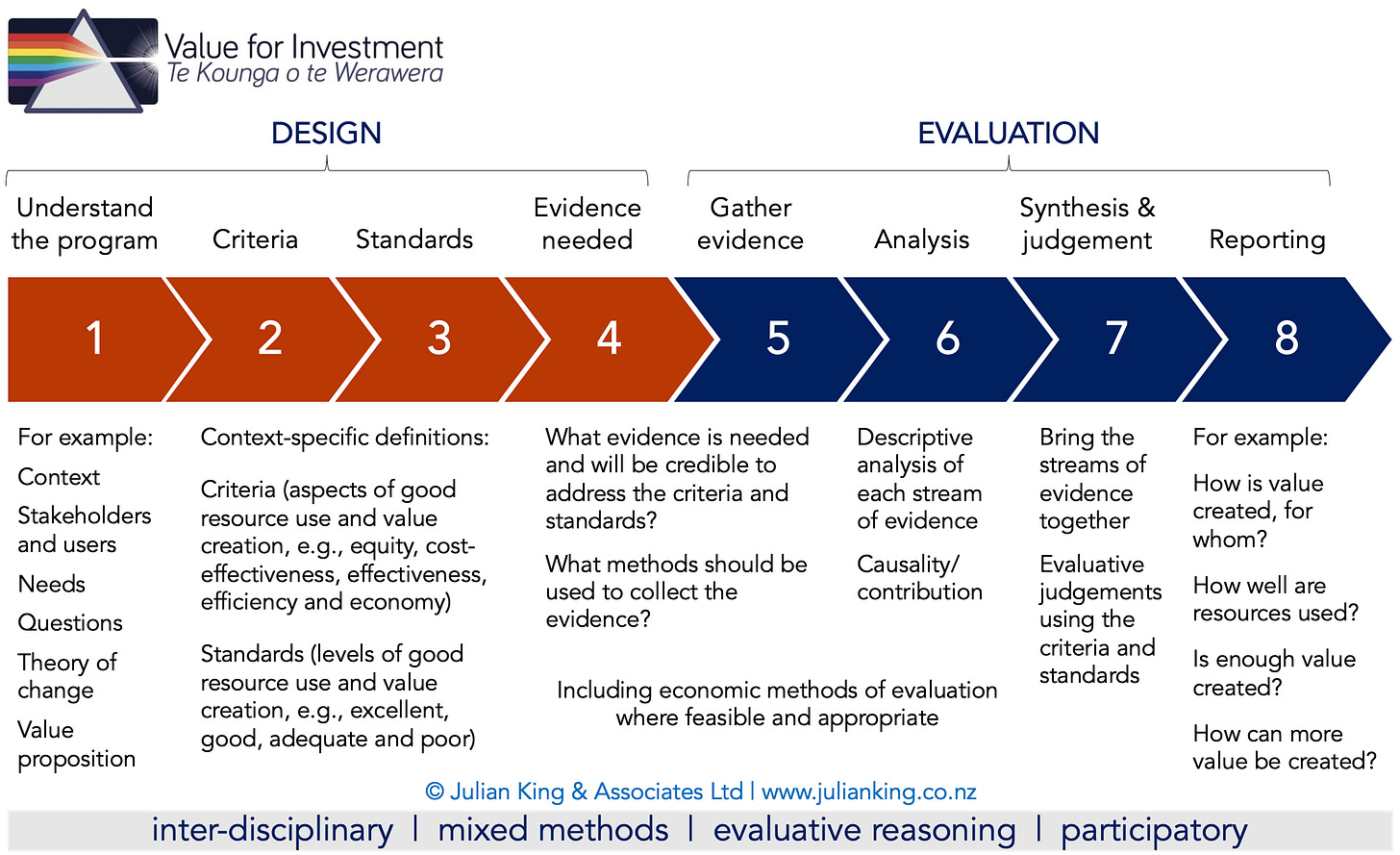

Understand the program

Before developing criteria and standards, it’s essential to invest time in understanding the program, its context, key stakeholders, and information needs. Work with stakeholders to establish a shared understanding of the program, its goals and functioning, and evaluation questions. This is step 1 of the process below.

It's useful to review relevant documents, such as business cases, policies, or contracts, to identify requirements and expectations that can inform rubrics. These documents can also guide discussions with stakeholders.

Co-developing a theory of change with stakeholders helps reveal assumptions and values, creating a shared framework for structuring an evaluation. If a theory of change already exists, reviewing it with stakeholders facilitates shared understanding and checks its fitness-for-purpose.

People may value different aspects of a program. Engaging stakeholders to define a program’s value proposition can add depth to a theory of change and support clearer rubric development, bridging the gap between change and value. See my recent article on value propositions.

Create a safe space for openness and collaboration

Evaluation is political, both in the obvious sense that it often relates to government and society, and in the deeper sense that it involves values, power dynamics and relationships as much as it does evidence. Added to that, evaluation can be scary, because a bit like taking an exam or being a medical patient, it may be experienced as being ‘done to’ and judged. It’s understandable that some stakeholders may feel apprehensive about taking part.

Whether you’re literally bringing stakeholders together in a real room, collaborating virtually in an online room, or even asynchronously via email or other means, our first task as facilitators is to create an environment that is conducive to open conversations and working together on a shared endeavour. This is just as important as the topic you’ve brought them together to discuss, and can take an investment of time to develop.

This isn’t a post on how to be a facilitator, and I assume you and your team are already on the lifelong journey of learning how to establish a welcoming vibe, set clear ground rules, model positive behaviours, manage power dynamics and conflict, use inclusive language and practices, foster a feedback-rich environment, and work adaptively to respond to the special uniqueness of each session (easy, right? 😅)

Our second task is to get the job done, surfacing diverse values while introducing structured ways of thinking about value. More on this below. It can help to warm up the group first by taking them through a simulation of the rubric development process, using a simple relatable scenario like choosing a car or rating a meal.

Encourage stakeholders to think holistically and analytically

Criteria are intrinsically analytic in that they single out specific dimensions of performance and value. But before analytically slicing and dicing a program into a list of criteria, it’s a good idea to view it holistically and systemically.

Asking directly about “what aspects of performance should we focus on?” can work OK with stakeholders who are used to thinking analytically (like policy analysts and researchers). But it’s usually helpful to be prepared with some conversation starters like “what would success look like to you?”, “what ways of working are important to help the program be successful?” and so on. (An advantage of defining the program’s value proposition before turning to rubric development is that it involves some of those conversation starters, effectively paving the way to defining value criteria).

I assume you already have your go-to facilitation techniques. However you do it, I suggest starting with activities that exercise the right hemispheres of participants’ brains - tapping into their creativity, intuition, tacit knowledge, visual and nonverbal thinking. Examples of facilitation techniques to encourage systemic thinking include rich pictures, role playing, or systems mapping. Then bring in the left hemisphere and start organising the concepts. Examples of left-brain facilitation tools include card sorting, classification trees, voting games etc. There’s a useful menu of options on the Better Evaluation website.

Suspend conversations about measurement

Rubrics define criteria and standards - not indicators. While indicators generally specify measurable attributes, rubrics describe broader aspects of performance, success, quality and value, in line with their intended purpose of helping people to make evaluative judgements.

This can cause a bit of discomfort for some participants, and a question is likely to arise, along the lines of “but how are you going to measure that?”

It’s important to set aside measurement decisions during rubric development. Once the rubric is defined, you can focus on identifying the right mix of evidence to support the evaluation (step 4 in the 8-step process pictured earlier in this article).

This sequence (first defining what matters, then addressing how it should be measured) has important advantages:

If we started by developing indicators, there’s a risk that we may confuse whatever we can measure or count with what’s important. To mitigate this risk we start by defining what’s important, and then discuss how to measure it.

Defining criteria may reveal gaps in available data by identifying something that is: a) agreed to be important; and b) not evaluable from existing evidence - potentially leading to recommendations to address these gaps.

Tailor rubrics to context

Criteria are specifically tailored to the program and often relate to a particular point in time (i.e. what would 'good' look like at the time of the evaluation). This means that definitions of criteria will differ for each program. Even if you use a given set of criteria, such as the OECD DAC criteria, they should be defined in terms that are specific to the program and context.

Keep it simple

Rubrics need to be specific enough to guide meaningful judgements, yet not over- specified to cover every contingency. Remember, you’re not writing a computer algorithm to make judgements for you. You’re not writing a piece of legislation that has to be free from loopholes. The rubric is just a guide to support transparent, focused-enough reasoning - and they’re more useful for this purpose if they’re kept relatively simple. Rubrics don’t make evaluative judgements - people do!

Be patient

The proverb, “measure twice, cut once” applies to rubric development. In other words, take the time to co-create well-formed rubrics. Check and re-check until stakeholders are satisfied. Rubric development is an iterative process and may go through multiple drafts. Investing in rubric development pays off throughout the remainder of the evaluation, aiding clarity at every step from gathering and analysing the right evidence to sense-making and report-writing. Stakeholders become more engaged as they see their expectations reflected and understand the basis for judgements.

Whatever it takes

There are infinite ways to design a participatory rubric development process, depending on the context. The bottom line is to meet people where they are and get their input. Here are a few examples from my experience, to illustrate:

A series of two-hour workshops with about 15 stakeholders, including mental health service users and different professional groups, where a rubric was created and refined in real time (using a laptop connected to a projector) until everyone endorsed it.

A series of online workshops across three time zones and two languages (with real-time translation) to iteratively develop a value proposition, criteria, and standards.

A half-day workshop with 20 scientists using post-it notes, followed by the evaluation team developing a draft rubric, and a second meeting to present the draft to the group and refine it together.

A full-day conference with over 100 doctors, nurses and practice managers, combining plenary and break-out sessions to develop criteria and standards.

A series of individual interviews, followed by some time at my desk developing a draft rubric, a workshop with stakeholders to refine it, and a one-on-one meeting to engage a key stakeholder who wasn’t at the workshop.

A multi-year evaluation, where year one focused on stakeholder engagement to develop rubrics that were used in subsequent years to assess system change progress.

An online meeting to refine tentative criteria that the evaluation team had developed from a theory of change.

A client developed their own draft rubric and emailed it back and forth till the wider stakeholder group and evaluation team reached agreement.

At a minimum, ensure key stakeholders understand and support the evaluation approach and the basis for judgements, even if they aren’t present during rubric development. The evaluation is more likely to be accepted as valid if evidence and reasoning are transparent, traceable, and linked to criteria developed or discussed with stakeholders from the outset.

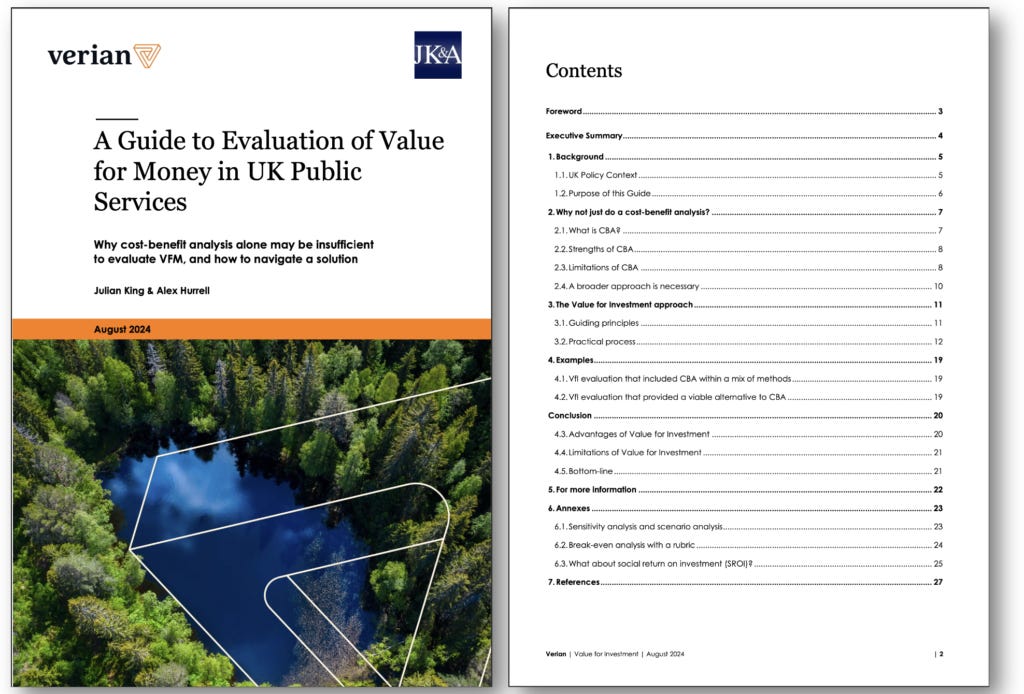

Ensuring Value for Money in Government Policy - webinar

On 5 December, 1-2pm GMT, Verian Group is launching its new Centre for VfM and I’ll be joining a panel with Alex Hurrell (UK Head of Evaluation at Verian Group), Lucie Moore (Head of the UK Government’s Evaluation Task Force) and Kirstine Szifris (President of the UK Evaluation Society. Follow the link above to find out more and register for the webinar.

This event also marks the launch of our recently published Guide to VfM evaluation that I co-authored with Alex Hurrell. Check it out to learn why we recommend mixing CBA with other evaluation methods and how you can provide clear answers to VfM questions using methods and tools evaluators already have.

Thanks for reading!

Acknowledgement

Many thanks to Alicia Crocket for peer reviewing this article. Errors and omissions are my responsibility.