Evaluative thinking

What is it? Why is it complex? Can we boil it down a bit?

Evaluative thinking is an important yet elusive concept: challenging to define or generalise about, complex to translate into something concrete and practical. But I’m going to try.

We can appreciate its complexity, but perhaps we also need something simple enough and memorable enough to guide our practice.

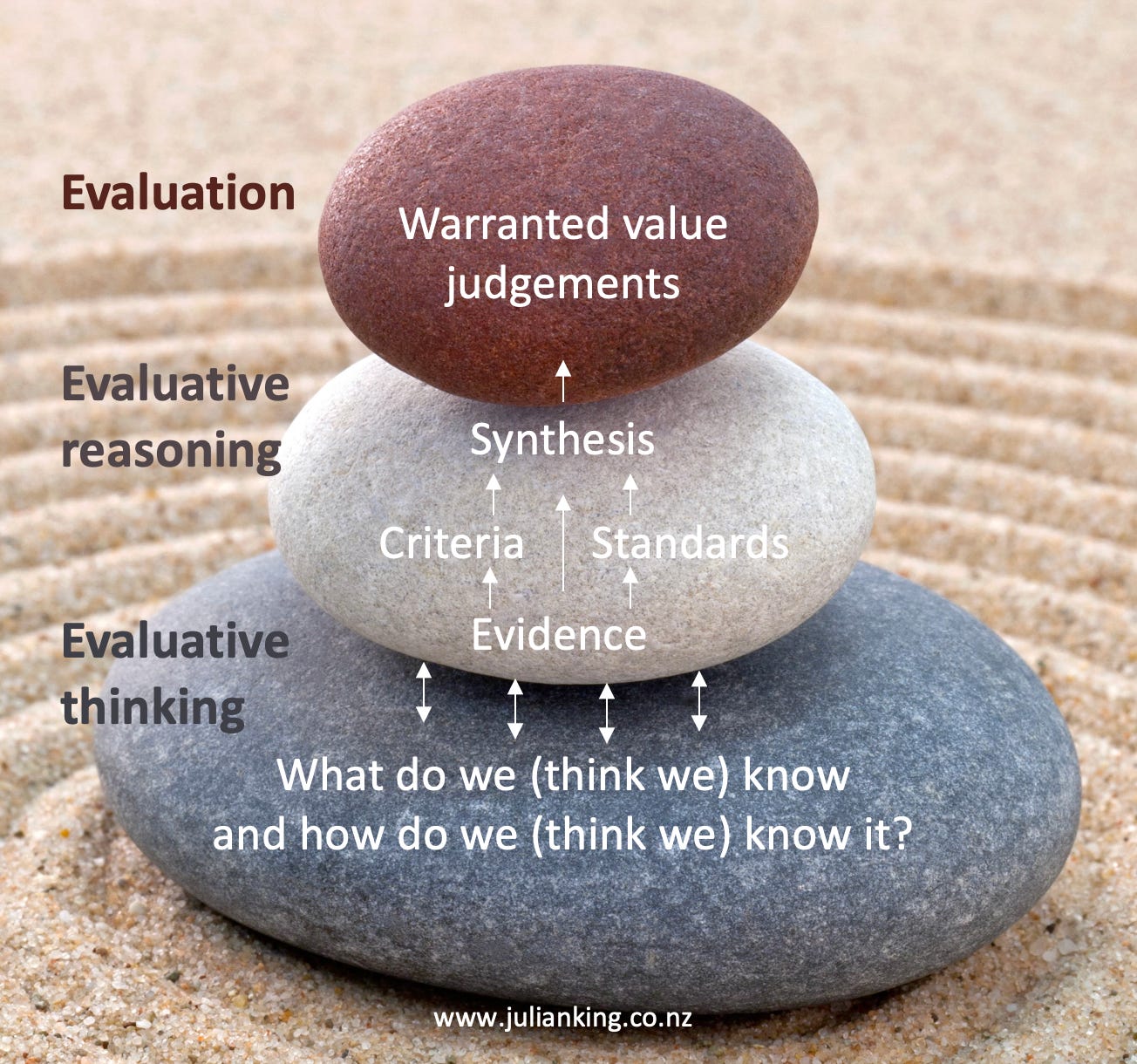

The way I see it, evaluation is supported by a process called evaluative reasoning which, in turn, is supported by a mindset and practice called evaluative thinking. Let me break it down.

Evaluation

Evaluation is essentially determining the value of something, like a policy, program, or intervention. It involves making value judgements, and those judgements should be warranted - supported by evidence and logical argument. That’s where evaluative reasoning comes in.

Evaluative reasoning

Evaluative reasoning is the process by which we get to a warranted value judgement. The process is supported by using explicit criteria (aspects of value) and standards (levels of value) as a scaffold to guide us in making sense of evidence and rendering a judgement, something like: program is [good] because [evidence] and [rationale].

The evidence we use in this process is diverse. Crucially, it includes evidence about values (what matters to people) which we use as the basis for defining criteria and standards. It also includes evidence about various aspects of the policy or program.

This evidence extends far beyond what we might simplistically call “facts”. For example, it can include empirical observations and measurements, inferences, probabilities, tendencies, theories, hypotheses, propositions, interpretations of incomplete or ambiguous data, scenarios, stories, expert opinions, syntheses of complex bodies of research, reports of subjective experiences, tacit and co-constructed knowledge from group discussions, data collected for one purpose and harvested for another, and more. It can come from qualitative and quantitative, comparative and stand-alone, prospective and retrospective, primary and secondary data.

All this evidence, and its use, is susceptible to errors, biases and uncertainties. Some pieces of evidence may be more reliable than others, but there’s no simple hierarchy. Our reasoning is fallible too. Analogously to George Box’s aphorism about models, all evidence and reasoning may be “wrong” in various ways, but some will be useful when we apply it thoughtfully. That’s where evaluative thinking comes in.

Evaluative thinking

Evaluation is a complex undertaking. To ensure we undertake each evaluation to a reasonable degree of quality and fitness-for-purpose, we should examine how we approach it, and each of its components (e.g., the criteria, standards, pieces of evidence, the process of combining them, the judgements) and ask ourselves whether we’re satisfied that they’re sound, that we’re interpreting them rigorously, and how we know. That’s evaluative thinking.

There’s a lot to think about

Evaluative thinking is complex too. The literature encourages us to apply a range of cognitive lenses (e.g., critical, creative, inferential, practical, conceptual, ethical, cultural, contextual, reflective, axiological). We can apply these ways of thinking to any and every aspect of:

the policy or program we’re evaluating (e.g., its context, the needs it addresses, its resources, what it does and why, its impacts, its value)

the evaluation we’re conducting (e.g., our context, the needs we address, our resources, what we do and why, our impacts, our value)

and, for the avoidance of doubt, this includes scrutinising (deep breath): the personal orientations, cultures, values, worldviews, ways of knowing, assumptions and biases we bring to the work; how we interact with and understand others who may have different orientations, cultures, values, worldviews, ways of knowing, assumptions and biases from our own; the cultural fit, relational and technical skills of the evaluation team; what values and whose values count; who has a right to a voice; who has power; approaches to evaluative reasoning and making judgements; approaches to making inferences about causality and contribution; sense-making strategies and frameworks; knowledge systems; methods and tools; what counts as credible evidence; who or what is privileged or marginalised by the methodological decisions we make and the boundaries we draw; the truth, beauty and justice of the evaluation story; the potential positive and negative consequences of the evaluation; and more.

So yeah, lots to think about - and all of it matters. Can we distil it into a simple principle that captures the essence and helps keep an evaluative mindset engaged?

Can we boil it down a bit?

I want to support high quality evaluations without derailing them with detail or paralysing them with perfectionism. For this purpose, a navigational aid compact enough to keep in my working memory is:

This question doesn’t replace the rich tapestry of important things we may need to consider. It holds the space for them. It’s a reminder to:

stay curious and a little bit sceptical

seek to understand not just what the evidence says but what it means

consider how we might be misguided and how we might do better

be alert to more information and different perspectives, even if (especially if) it means changing our minds.

This is also why I think evaluators shouldn’t work alone. Many’s the time a colleague, or a real expert in a program (e.g., stakeholder, rights-holder, end-user, kaupapa partner) has noticed something that I didn’t pick up on, or we’ve made sense of an issue collectively. Evaluative thinking is “a collaborative, social practice”.

Digital watches

The career we choose (or that chooses us) influences how we see the world. Dentists notice smiles, architects notice the built form and how we inhabit spaces, and evaluators are maybe a little inclined to notice the flaws in our everyday, conversational, informal logic - spurious attribution, false precision, weak premises, unstated assumptions, etc.

Or is that just me? On-brand since 1978, when I got into an argument with a boy in my class who said digital watches always tell the right time. I’m slowly learning to 🤐 when off-duty.

It’s this mindset that led me to dig into the foundations of cost-benefit analysis, concluding that it has unique strengths and we should use it in program evaluation, and that in light of its limitations we should use it not as a stand-alone method but in contextually responsive ways, in combination with other methods. CBA looks at value from a very specific perspective, and we need more perspectives than that.

I share these examples to illustrate how an evaluative mindset leads us to question things in ways that can strengthen our practices and products. Whatever methods we apply, they can focus our attention on some aspects of a thing while potentially leading us to not notice other aspects. The formal reasoning we apply in program evaluation is strengthened when we’re cognisant of that.

Which is why the following quote (often attributed to W. Edwards Deming), feels incomplete, naive and misleading.

In God we trust. All others must bring data.

I assume we can substitute any divine nature or higher power into the first part of the statement. But when it comes to evaluation, we need more than beliefs. We need warrants.

And as for the second part, “all others must bring data”, that’s not good enough. It’s digital watches all over again. As we know, facts are value-laden and, in our business, often uncertain.

How about:

In evaluative thinking we provisionally trust. Bring explicit values, multiple lines of evidence, and a curious mind.

Conclusion

We evaluators need more practical guidance on evaluative thinking. I’m sharing three references below that I find helpful for their comprehensiveness, concreteness, and clarity. But they’re too much to keep in my head. A simple question I carry with me is:

What do we (think we) know and how do we (think we) know it?

In a suitably evaluative spirit, I expect these thoughts are probably wrong in some ways, but nevertheless hopefully useful, and will continue to evolve.

Let me know what you think. How would you sum up evaluative thinking in a few words?

Many thanks to Dr. Patricia Rogers for peer review of this post. Any errors or omissions are my responsibility.

Recommended reading

Comprehensive: Vo, A.T., & Archibald, T. (Eds) (2018). Evaluative Thinking. New Directions for Evaluation.

Concrete: Cole, M. J. (2023). Evaluative thinking. Evaluation Journal of Australasia, 23(2), 70–90.

Clear: NSW Education (2023). Evaluative thinking. Web pages.

Great post. Thank you Julian.

Love this post. Will check also the recommended readings. Thanks Julian