Towards Made-in-Africa Value for Money Assessment

Sharing my presentation at the African Evaluation Association (AfrEA) Conference

Today I’ve been at the AfrEA Conference in Kigali, Rwanda, catching up with colleagues from evaluations past and present and immersing myself in African perspectives on the future of evaluation.

Highlights from the sessions I attended today were a presentation from Dr. Almas Fortunatus Mazigo from Dar Es Salaam University College of Education on a Philosophy of Evaluation Based on Swahili Wisdom, and a keynote from Tade Aina, Chief Impact and Research Officer at the Mastercard Foundation, sharing the Foundation’s Strategy to Promote and Expand Employment Opportunities for Young People in Africa. Both presenters emphasised in different ways the importance of honouring indigenous values, insights, knowledge, and ways of knowing to decolonise evaluation. I also attended some presentations on AI in evaluation, from which I draw a sense of optimism about the potential of AI to work for the betterment of evaluation, for example by freeing up our time to invest where it is most needed - in the relational aspects of our work.

Towards Made-in-Africa VfM Assessment

My contributions to the conference included a full-day professional development workshop on Monday and a short presentation today, both on the theme of Made-in-Africa Value for Money (VfM) assessment. In this post I’ll outline the short presentation. The workshop is available on request - get in touch.

Who am I?

First let me address the 🐘 in the room: who am I to talk about Made-In-Africa VfM? I am not made in Africa. I’m a New Zealand-based public policy consultant of mostly Scottish and English descent. I specialise in evaluation and value for money, and I’ve had the pleasure and privilege of contributing, as an outsider, to VfM assessments in Mozambique, Rwanda, Kenya, Uganda, Ethiopia, Somalia, Nigeria, Ghana, and Zambia. Here, I wanted to share some ‘made in New Zealand’ models in case they are useful in facilitating paradigm shifts in African VfM assessment by confronting questions like, value to whom?

What’s this presentation about?

There are various methods and tools for assessing value for money. From economics, methods like cost-benefit analysis seek to quantify whether a policy or program generates more value than it consumes. Social Return on Investment (SROI), favoured in impact measurement circles, offers a parallel yet distinct lens. The international development sector contributes the '5Es' (economy, efficiency, effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, equity) and associated performance indicators to the discourse. Amidst these approaches, evaluators find themselves in a quandary, equipped with a broad toolkit of methods but unsure how to apply them to VfM and sometimes wondering whether existing approaches to VfM are fit for purpose (King, 2017).

In this presentation, I suggested that VfM assessment has focused too much on methods and not enough on attending to the values of different people and groups and their right to have a say in what constitutes good VfM. Evaluators can harness insights from both evaluation and economics, integrating them with ethical considerations and diverse evaluation tools, methods and approaches. In particular, this presentation proposed the use of sound evaluation practices to promote Made-in-Africa VfM assessment, rooted in African values. These existing practices can contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of VfM, ultimately supporting well-informed evaluations, good resource allocation decisions and positive impacts.

Power is central to evaluation

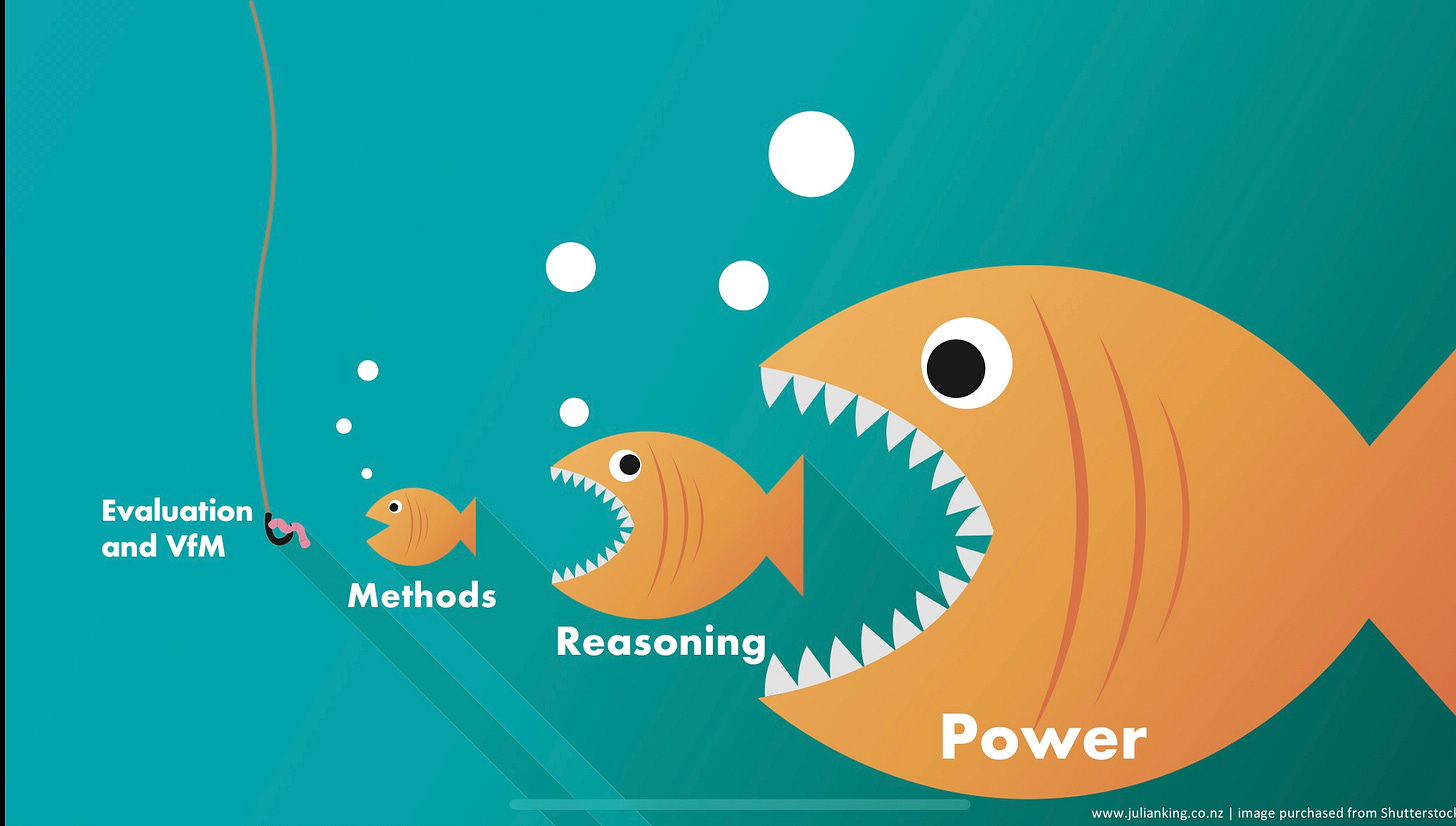

When considering what constitutes good practice in evaluation, the conversation will often turn to methods of data gathering and analysis, and what counts as credible evidence. Undoubtedly, reliable evidence is crucial. However, evaluation isn’t only about methods. Fundamentally it is about reasoning (how judgements are made from explicit values and evidence) and even more fundamentally it is about power (e.g., who gets a say in what values and evidence matter and how the evaluation should be conducted) (King, 2023b).

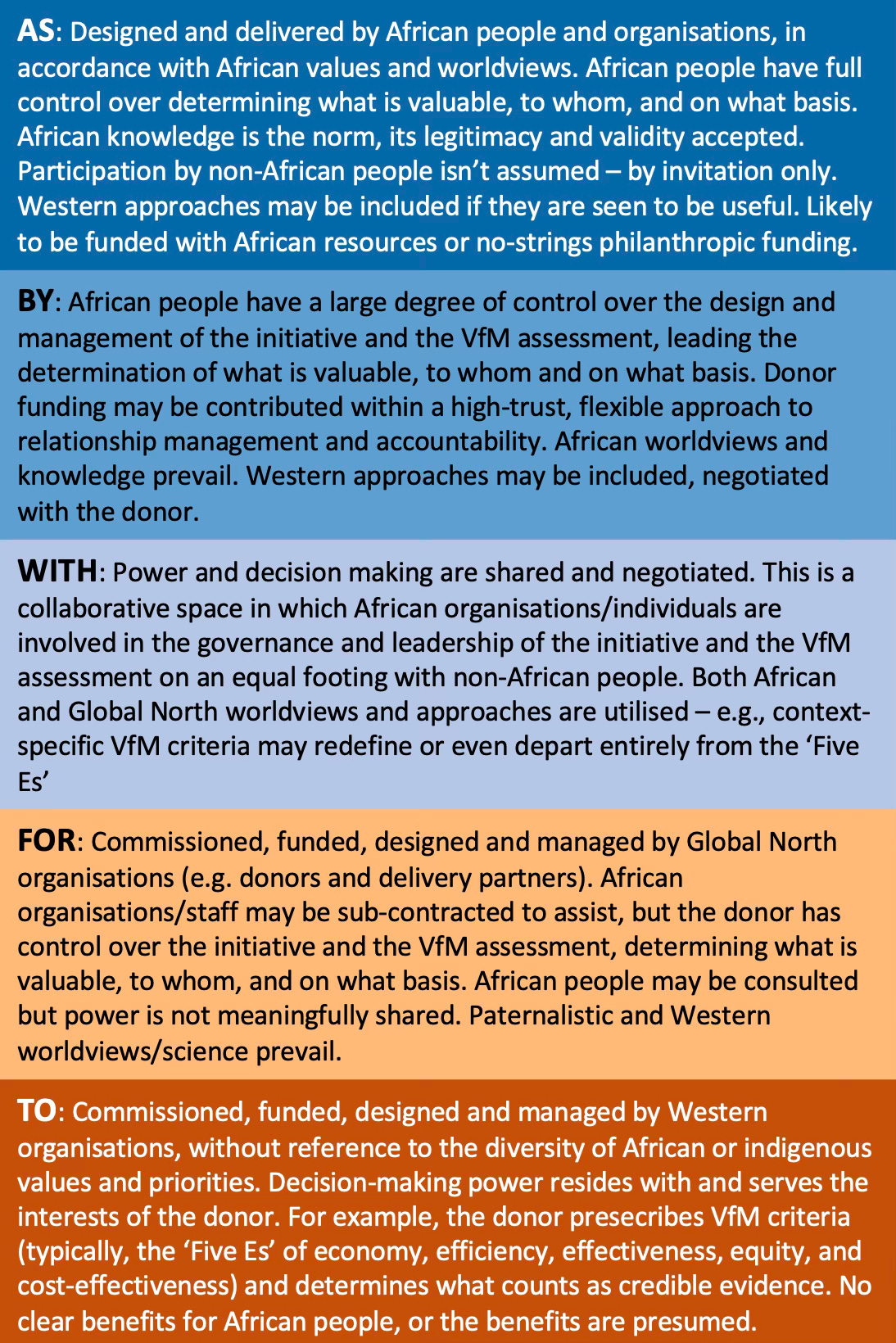

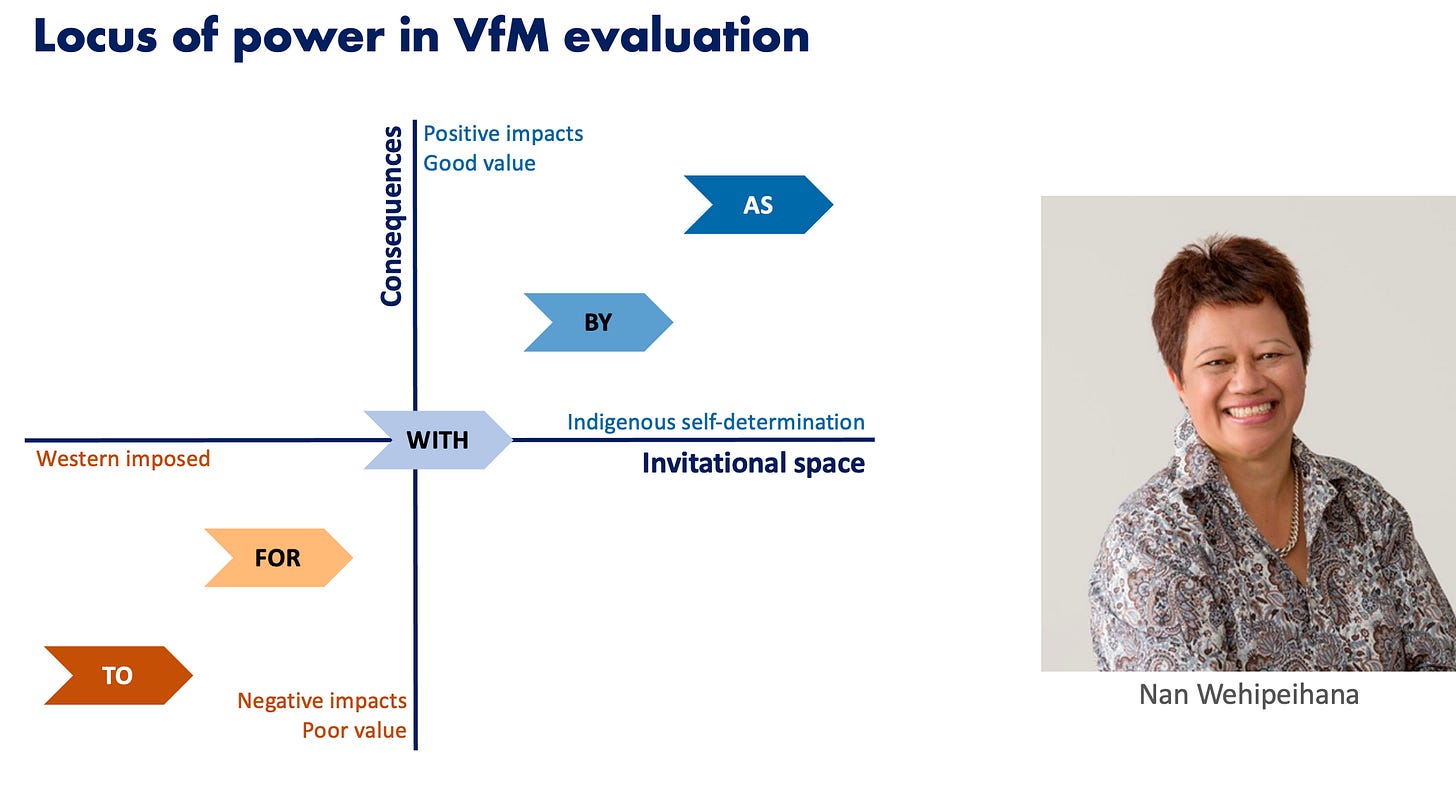

My colleague Nan Wehipeihana developed a model for individuals and organisations involved in evaluation to assess how they share power and decision-making with indigenous people (Wehipeihana, 2013; 2019). The model distinguishes between evaluations done to, for, with, by, or as indigenous people. These five prepositions describe where the locus of power sits along a continuum from Western to Indigenous power and control. Nan’s model has since been adapted for use in contexts where individuals or communities seek to lead their own development or where power differentials exist. With Nan’s input and endorsement, I adapted her model for VfM evaluation (King, 2023c).

What could Made-in-Africa VfM evaluation look like?

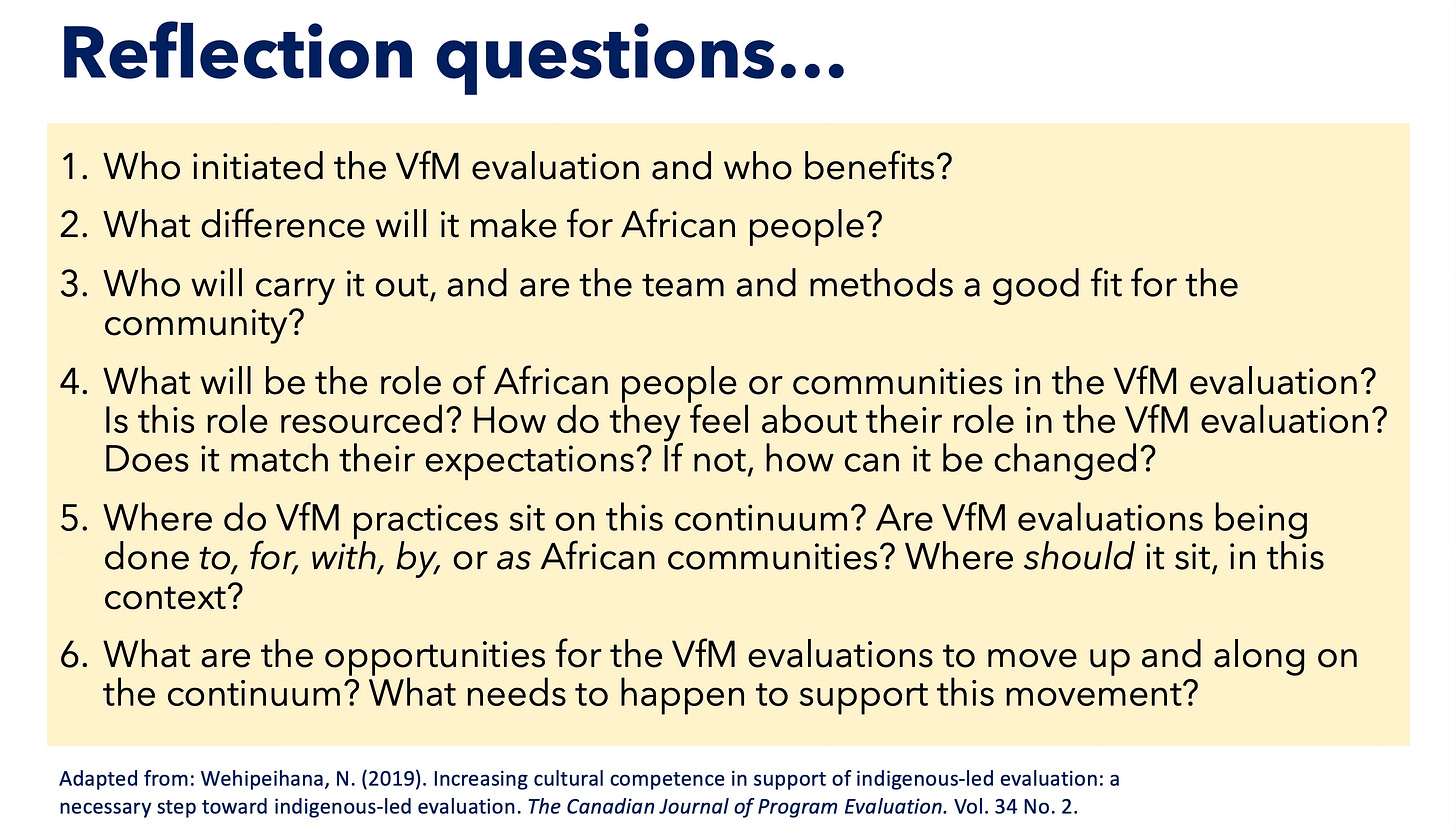

Nan Wehipeihana’s model offers a framework to reflect on the current state of VfM evaluation in Africa. Bearing in mind: i) that the purpose of VfM evaluation is to determine whether a policy or program is a good use of resources, whether it creates enough value and how it can create more value; and ii) that value is the merit, worth or significance that people and groups place on something (Gargani & King, 2023), then it becomes necessary to confront some important questions:

Which people and groups get to place value on a policy or program, its resource use and its impacts?

When a policy or program affects African communities, who has a right to participate in determining what is valuable, to whom, and on what basis?

Who has a right to lead this determination? (King, 2023c).

The following adaptation of Wehipeihana’s (2013; 2019) model outlines five scenarios which lie on a continuum from Western-owned to African-owned VfM evaluation:

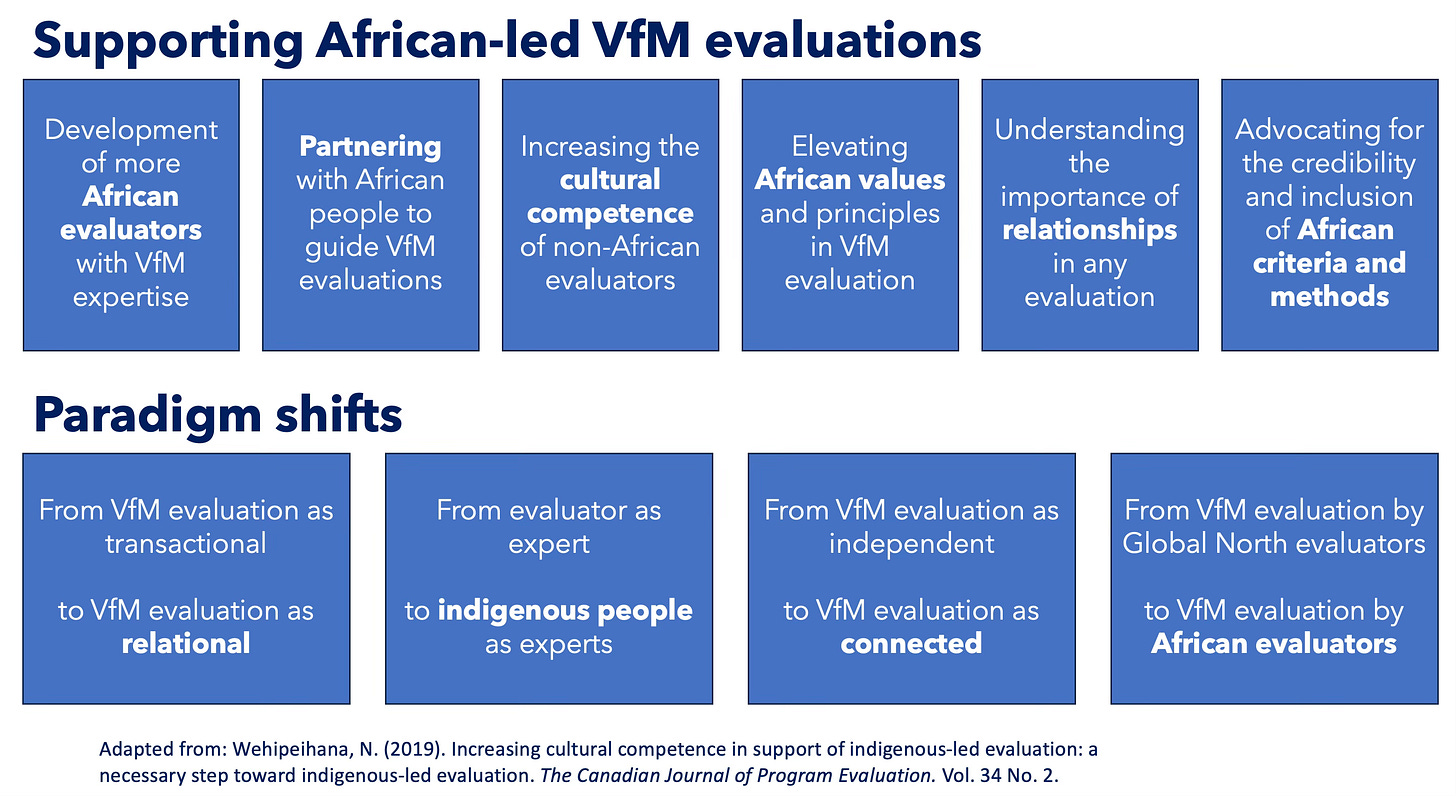

There are many moving parts to supporting African-led VfM evaluations. Moreover, shifting the locus of power necessitates a series of paradigm shifts (Wehipeihana, 2019):

Navigating donor needs and wants

VfM evaluations are often conducted at the request of donors. But the underlying imperative of making good decisions with limited resources is universal. Donors continue to have a lot of power in the design, criteria, evidence, methods and conduct of VfM assessments (and of evaluations more generally). Nonetheless, I believe we can disrupt VfM evaluation to deliver what donors and communities need to be well informed about the value generated through the resources invested in programs and policies. As we move toward Made-in-Africa VfM evaluation, we can reflect on the sectors and settings where we work and consider the following:

These reflective questions can be asked at every step of a VfM evaluation, from its commissioning (e.g., who initiated it and were the relevant African communities consulted?), managing the VfM evaluation (e.g., who are the stakeholders, are African people represented, and are decision-making processes equitable?), the design of the VfM evaluation (e.g., are African principles and methods included in the design and are African evaluators, and ideally local people, part of the VfM evaluation team?), data analysis (e.g., is there a process for checking the accuracy and cultural validity of data analysis and evaluative judgements?) and dissemination (e.g., how will the VfM evaluation findings be shared with African communities?) (Wehipeihana, 2019).

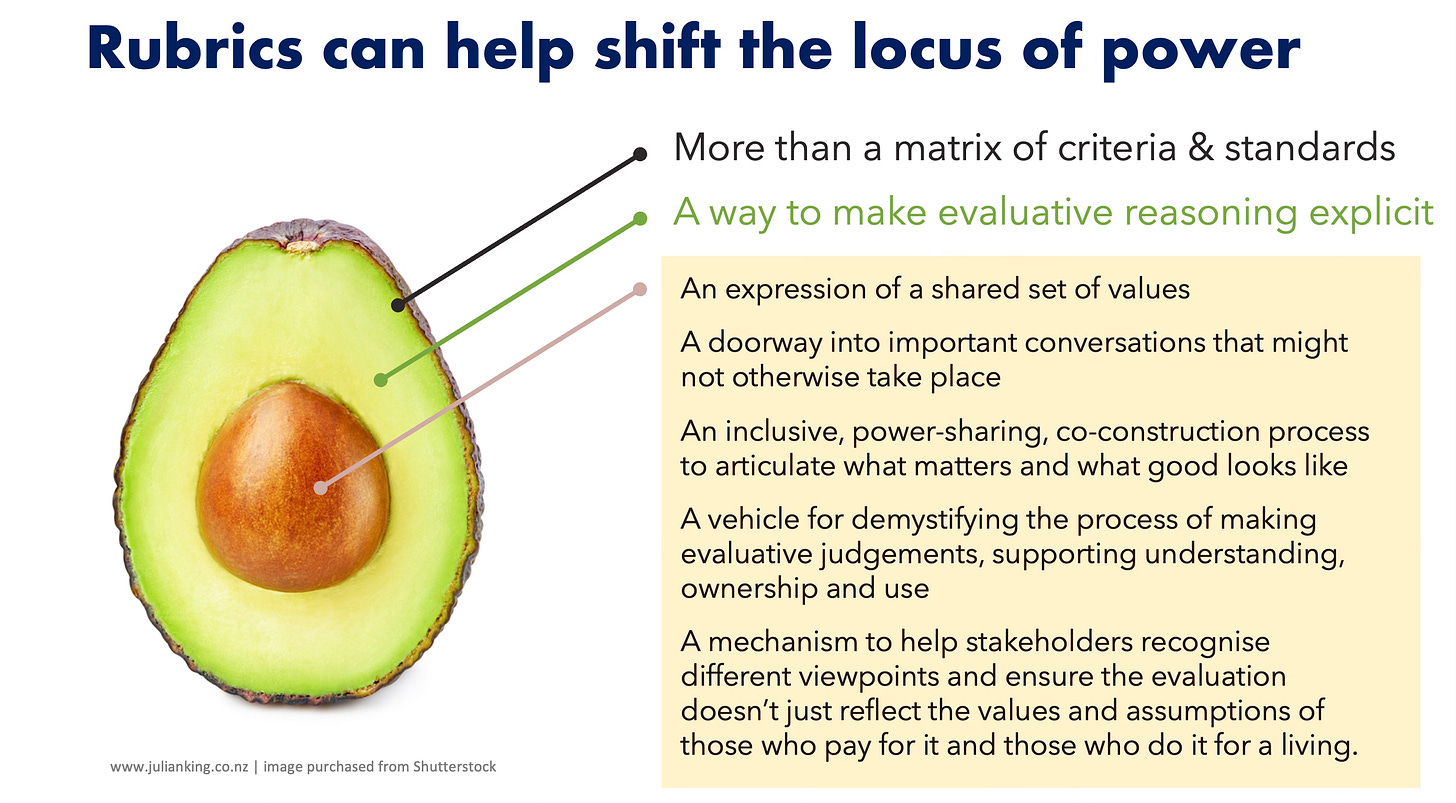

Rubrics: A tool for explicit evaluative reasoning and shifting the locus of power in VfM evaluation

Rubrics are intuitive and versatile evaluation tools. Superficially, a rubric can be described as a matrix of criteria (aspects of value) and standards (levels of value). Beneath the surface, a rubric supports clarity in evaluation by making evaluative reasoning explicit. But at their heart, rubrics support relational evaluation and power sharing in determining what good looks like (King, 2023e). The processes of co-creating rubrics and using them to make evaluative judgements bring stakeholders to the table to make sense of values and evidence through deliberative dialogue.

From ‘Value for Money’ to ‘Value for Investment’

Communities, donors, decision-makers, policy and program evaluators understand the importance of making good decisions in the face of constrained resources, but existing methods and tools have struggled to provide clear answers to questions such as: How well are we using resources? Is this resource use creating enough value? How can we create more value from these resources? (King, 2023a).

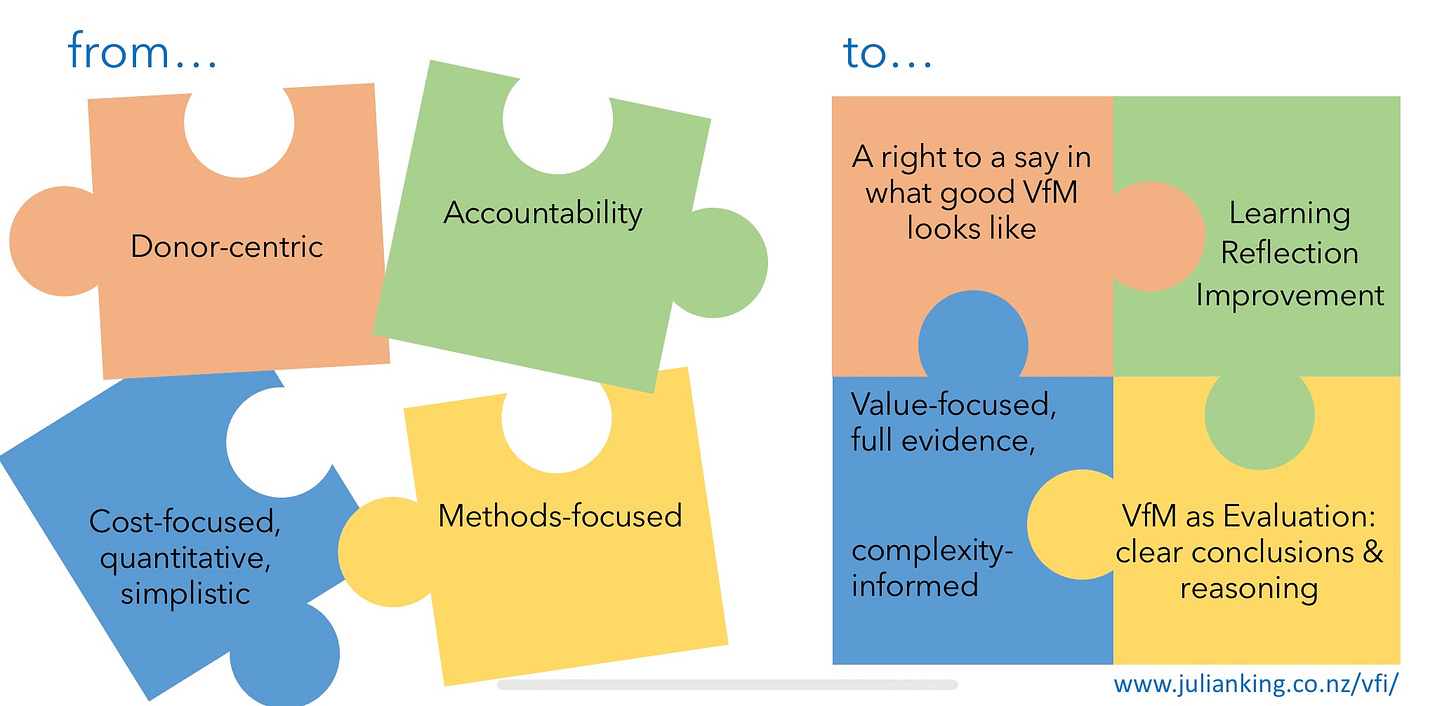

VfM assessment is too often:

Donor-centric, with insufficient attention to the perspectives of communities who are supposed to benefit from an intervention

Accountability-focused, missing opportunities to inform learning and improvement

Simplistic, ignoring complexities of real-world programs

Distracted by the money and unclear about the value: focused on cost reduction, quantitative evidence and monetary valuation, leaving stakeholders feeling short-changed when the assessment doesn’t adequately capture the value of a policy or program (King, 2023a).

We’re on a mission to change that. The Value for Investment (VfI) approach is designed to address these challenges (King, 2017; 2019a; King & Oxford Policy Management, 2018; 2023) - the first African example of its use being the MUVA program in Mozambique (King, 2019b) who also gave an excellent presentation today on embracing a test-learn-adapt approach to monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL), enabling the design and development of innovative strategies for economic empowerment.

A starting premise of the Value for Investment approach is that VfM assessment is evaluation (King, 2017). The approach is underpinned by the use of rubrics that are co-created and agreed in advance of the evaluation. This approach is designed to make values explicit. It doesn’t prescribe what those values should be - but it does advocate for those values to include the perspectives of people and communities affected by the program and those with a right to a voice. And that requires us to think beyond indicators to understand and communicate the value story behind the numbers (King, 2024). The approach follows a sequence of steps which are designed to be collaborative and inclusive:

The VfI approach enables rigorous evaluation of VfM in contexts where economic methods and metrics are challenging to apply or insufficient to comprehensively evaluate program resources, processes, consequences and value. The approach is able to explore value in multiple ways, such as social, cultural, environmental and economic value, as well as incorporating concepts often associated with VfM such as efficiency and equity. It’s in use worldwide, and open-access.

Conclusion

Evaluation can and should support self-determination as a process, an outcome, an enabler of outcomes and a value creation mechanism. Nan Wehipeihana’s Locus of Power model offers a framework to reflect on VfM evaluation in Africa. The Value for Investment approach encourages evaluators to use rubrics, mixed methods and collaboration to share power, co-create value and provide meaningful answers to VfM questions. Together, these models represent potential tools that can support steps toward Made-In-Africa VfM evaluation.

References

Gargani, J., King, J. (2023). Principles and methods to advance value for money. Evaluation, 1-19. DOI: 10.1177/13563890231221526.

King, J. (2017). Using Economic Methods Evaluatively. American Journal of Evaluation, 38(1), 101–113.

King, J. (2019a). Evaluation and Value for Money: Development of an approach using explicit evaluative reasoning. (Doctoral dissertation). Melbourne, Australia: University of Melbourne.

King, J. (2019b). Combining multiple approaches to valuing in the MUVA female economic empowerment program. Evaluation Journal of Australasia, 19(4), 217-225.

King, J. & OPM (2018). OPM’s approach to assessing value for money – a guide. Oxford Policy Management Ltd.

King, J., Wate, D., Namukasa, E., Hurrell, A., Hansford, F., Ward, P., Faramarzifar, S. (2023). Assessing Value for Money: the Oxford Policy Management Approach. Second Edition. Oxford Policy Management Ltd.

King, J. (2023a). Welcome to Evaluation and Value for Investment. Retrieved from: https://juliankingnz.substack.com/p/contents

King, J. (2023b). Navigating criticisms of evaluation methods: 5 tipe to increase evaluation quality, satisfaction, and deal with criticisms constructively. Retrieved from: https://juliankingnz.substack.com/p/navigating-criticisms-of-evaluation

King, J. (2023c). Locus of power in VfM assessment: building on a model by Nan Wehipeihana. Retrieved from: https://juliankingnz.substack.com/p/locus-of-power-in-vfm-assessment

King, J. (2023d). Unpacking Value for Investment Jargon. Retrieved from: https://juliankingnz.substack.com/p/vfi-thesaurus?r=8fet1&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&open=false

King, J. (2023e). Sense-making with stakeholders and rubrics. Retrieved from: https://juliankingnz.substack.com/p/sense-making-with-stakeholders-and

Wehipeihana, N. (2013). A Vision for Indigenous Evaluation. Keynote presentation at Australian Evaluation Society International Conference, 2013, Brisbane. Retrieved from: https://communityresearch.org.nz/vision-for-indigenous-evaluation/

Wehipeihana, N. (2019). Increasing Cultural Competence in Support of Indigenous-Led Evaluation: A Necessary Step toward Indigenous-Led Evaluation. Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation, 34(2). DOI: 10.3138/cjpe.68444