Smarting a bit from a reviewer’s comment on a journal article I contributed to. The article, written (very well I might add) by a PhD student, shares a Value for Investment (VfI) study. It targets a primary audience who are familiar with the sector where the study was done, but may be unfamiliar with the field of evaluation. The paper focuses mainly on sharing the content of the study, but also aims to introduce the VfI approach and some core evaluation principles.

In this post, I’ll share the reviewer’s critique, my response, and some reflections on lessons for academic publishing. But first:

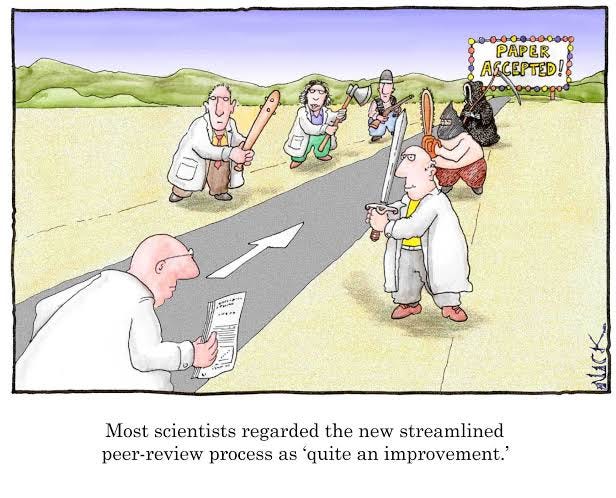

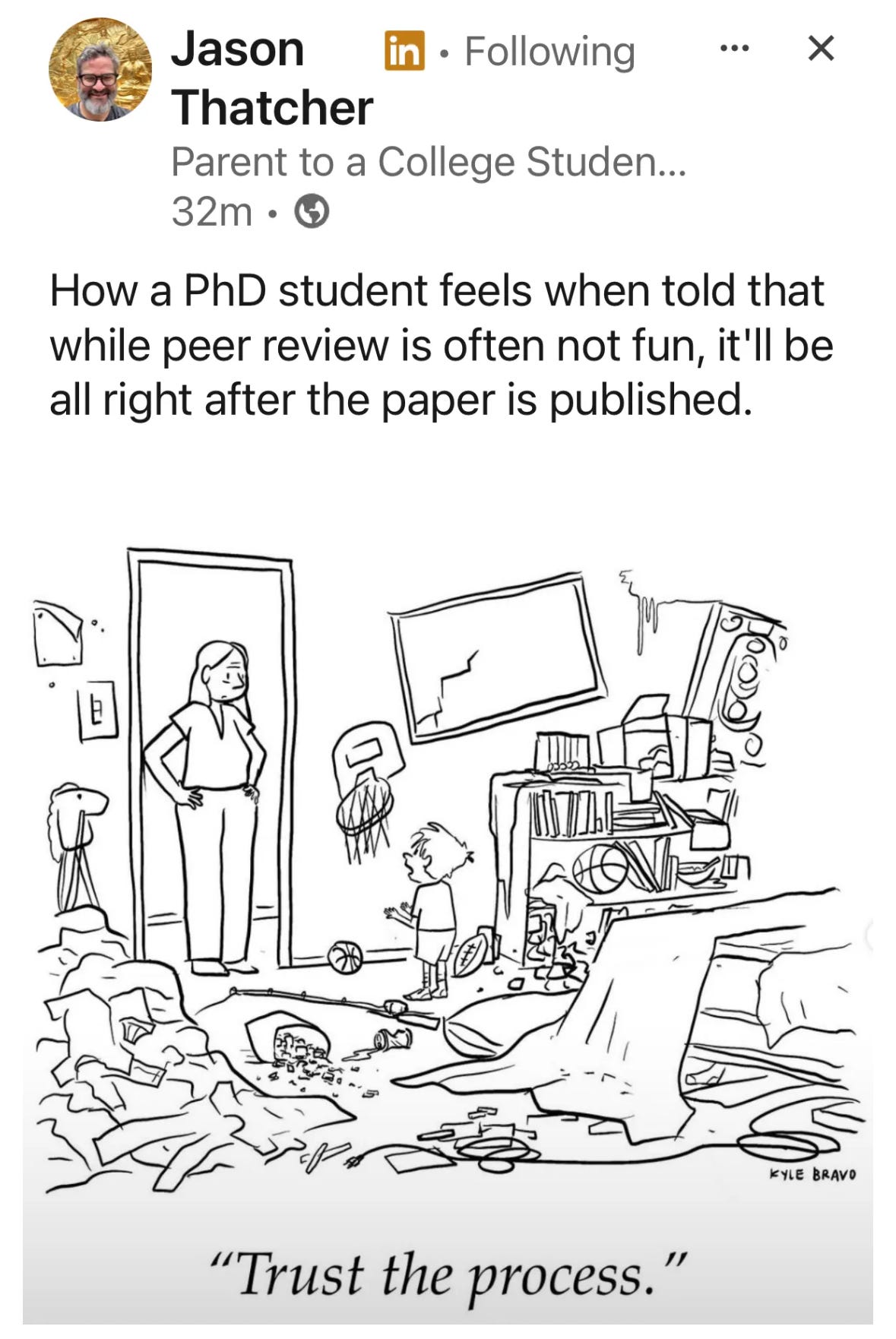

Reviewer 2 - the meme genre

Reviewer 2 has become a whole category of memes, an inside joke among researchers who submit their work to peer-reviewed journals. Reviewer 2 represents the archetype of the overly critical, nitpicky, or hostile peer reviewer.

“Reviewer 2” is literally the anonymised label given to the second reviewer in a manuscript review process - and since editors like to sandwich bad news between pieces of good news, the most critical comments are often associated with the second reviewer, with the first and third reviews being more positive.

However, the meaning of “Reviewer 2” has taken on a broader status as the embodiment of all that can go wrong in peer review. The memes expose real issues in academic publishing such as reviewers being able to hide behind anonymity, the idiosyncratic subjectivity of their feedback, and the emotional toll of harsh criticism.

The mythical Reviewer 2 portrayed in memes often displays characteristics such as:

Grumpy and aggressive - unnecessarily critical or mean-spirited

Vague and unhelpful - comments lack specificity or actionable advice

Overly committed to pet issues - fixating on minor details that aren’t central to the paper

Self-interested - insisting authors cite the reviewer’s own work, even when it is barely relevant

Unwilling to treat authors as peers - their tone can be condescending or dismissive, making authors (especially those at the beginning of their academic careers) feel belittled.

Although Reviewer 2 of meme lore is an exaggerated, humorous reflection of the sometimes frustrating realities of academic peer review, the memes are popular because they’re cathartic; just about everyone in academia has lived experience of this phenomenon.

But I digress.

Reviewer 2 - the actual

This is Reviewer 2’s actual feedback on our paper - in full:

This paper poses the question: "Do stakeholders of a program who a priori strongly support this program for various reasons (e.g., their paychecks are through the program) state in a survey that they support the program?" Obviously, the answer is "yes" and this is what the authors find. Maybe they do things differently in New Zealand but in all countries I'm familiar with, this wouldn't be taken seriously as a way of ascertaining whether or not a program is worthy of support. So, the results of this paper are profoundly uninteresting.

Ouch. And also:

Talk about feeling completely misunderstood. Did they actually read the article?

We didn’t respond directly to the reviewer since the article was rejected outright. However, I do think it’s valuable to share what we would have said, as it addresses recurring themes when it comes to researchers peer reviewing evaluation articles - and we do want to get our evaluations published in journals that reach subject matter specialists, who are generally research-trained and may be unfamiliar with evaluation - right?

Responding to the critique

Dear Reviewer 2,

You claim that involving stakeholders in making judgements about the program’s quality and value is akin to asking people who support the program whether they support the program. This critique fundamentally misunderstands the nature of evaluation, the methodological rigour involved, and the value of stakeholder engagement in evaluation.

Evaluation is a judgement-oriented practice

Evaluation is the systematic determination of merit, worth and significance.1 It aims to provide robust insights into such matters as how good an intervention is, whether it is good enough, and how it can be improved.2 This is by necessity “a judgment-oriented practice - it does not aim simply to describe some state of affairs but to offer a considered and reasoned judgment about the value of that state of affairs”.3

This feature of evaluation is underpinned by a logic that involves interpreting evidence through the lens of explicit criteria (aspects of performance) and standards (levels of performance) to transparently judge the value of something - a process known as evaluative reasoning.4 In this context, value is understood as the regard or importance assigned to an intervention and its impacts. Consistent with this interpretation, interventions do not possess inherent value; rather, people assign value based on their perspectives and experiences.5

Accordingly, engaging with the right people - those who affect or are affected by the program - is an important part of the process.

Stakeholder involvement is a strength, not a weakness

Stakeholder involvement contributes to informed, considered judgements, not mere opinion polling. Stakeholders bring a diverse range of perspectives, including those with direct experience of the program’s implementation and impact. Their involvement ensures the evaluation is grounded in real-world context.

Engaging stakeholders in evaluation design and judgement-making increases the legitimacy and utility of the evaluation findings, as those affected by the program are directly involved in assessing its value. Evaluations that engage stakeholders are more likely to be used and influence practice. Conversely, excluding stakeholders can result in evaluations that lack relevance and buy-in.

In many evaluation paradigms, involving stakeholders is not only a methodological choice but also an ethical one, democratising the process, respecting their agency, and ensuring they understand and endorse the process and its products. The alternative is to exclude the values of those whose lives are impacted - which many would argue is unethical.

Explicit criteria and standards guard against individual subjectivity and self-interest

The evaluators did not simply ask stakeholders for their opinions. Rather, the evaluation team collaboratively developed explicit, pre-defined criteria and standards with a diverse group of stakeholders. This approach ensures that judgements are anchored in agreed definitions of quality and value that were set in advance. The criteria and standards are explicitly linked to the program’s theory of change and value proposition, ensuring a logical and transparent flow from intervention design to findings. The process is transparent and replicable - anyone reviewing the evaluation can see exactly how judgements were made and on what basis.

This evaluation also involved stakeholders in deliberating on evidence and rating the program’s performance against the criteria and standards. The range of ratings stakeholders gave for each criterion was transparently reported. This structured process seeks to understand why and how stakeholders assigned value, and whether the ratings hold up against the explicit criteria, standards and evidence.

Stakeholders’ evaluative ratings, when systematically and transparently assessed, can reveal nuances about program strengths, weaknesses, and areas for improvement that are not accessible through external assessment alone. Indeed, stakeholders rated the program Adequate to Poor on some criteria and more highly on others, highlighting strengths and areas for improvement.

Additional checks against bias are built into the evaluation design

In any study, potential for bias exists. While the collaborative development and use of criteria and standards reduces the potential for personal biases and vested interests to sway judgements, it also introduces other specific risks, such as groupthink or powerful voices dominating. Recognising these risks, our evaluation design is intentionally structured to manage and mitigate them.

Robust checks against bias are systematically built into the evaluation process. This includes seeking diverse stakeholder perspectives, anonymous scoring mechanisms, external facilitation, and full transparency in the development of criteria and standards, as well as in the structured evaluative reasoning process for making and reporting judgements.

Judgements are evidence-based

Stakeholders did not make judgements in a vacuum. Their assessments are grounded in a comprehensive and balanced evidence base drawing from relevant literature, previous evaluations of the intervention, and routinely collected monitoring data. Triangulation of reliable evidence from multiple sources further reduces bias and enhances the credibility of findings.

The approach aligns with accepted good practices in evaluation

Evaluation is context-sensitive and designed to produce findings that are actionable and meaningful for decision-makers and program stakeholders. The use of explicit evaluative reasoning, mixed methods, and participatory evaluation approaches, are widely recognised for their contributions to rigour and their ability to produce actionable, context-sensitive findings.6

Conclusion

Reviewer 2, your argument overlooks core tenets of evaluation theory and practice, including the nature of evaluative reasoning, the value of structured stakeholder engagement and the methodological safeguards used to mitigate bias. The process described in our paper is not one of asking supporters if they support the program; it is about making transparent, evidence-and-criteria-based judgements with the involvement of those who are best placed to understand the program’s context and impact. This approach is both rigorous and widely endorsed in the evaluation literature.7

Lessons for academic publishing

Am I just salty ‘cos we got a bad review? Yes I’m salty. Constructive feedback is welcome. We’re always open to improving our work. However, Reviewer 2’s feedback was condescending and intriguingly passive-aggressive (What was going on for them? How did they experience this moment?).

The dismissive tone indicates a lack of constructive engagement with the article. The wholesale rejection of our study as “profoundly uninteresting”, with the sarcastic barb, “maybe they do things differently in New Zealand,” suggests underlying dynamics of gatekeeping, in-group bias, and intolerance of perspectives and methodologies that differ from the reviewer’s own.

The attitude and conduct - taking the opportunity to insult not only the authors (a PhD student, two senior academics, and me) but our whole country into the bargain - not only diminishes the potential for collegial dialogue but also contravenes recommended practices in peer review, which advocate for professionalism, respect, and formative feedback to foster scholarly development.

Journal editors are not required to pass on unprofessional or hostile peer review comments to authors. Instead, they have both the authority and ethical responsibility to intervene and ensure that all feedback shared with authors is helpful and respectful. The fact that this feedback was passed on to us raises questions for me about the journal’s editorial culture and standards.

A key lesson for academic publishing - especially outside of evaluation journals - is that peer reviewers are often senior figures in their research fields but may have little or no grounding in evaluation theory or practice. This mismatch can lead to misunderstandings, as reviewers may judge evaluation studies by research standards that don’t always apply, potentially overlooking unique contributions and methodological strengths that evaluation brings to the table. It’s worth bearing this in mind when writing up our methodologies.

Bottom line

Reviewer 2 incidents happen from time to time. Sometimes they make a good point in a bad way. Sometimes it’s not clear that there is a point. We can be thick-skinned and move on, but I think we should expect better.

I’ve also had some very good experiences with the peer review process, where reviewers’ comments were direct, specific, and delivered in a constructive, encouraging way. Part of our job as academics is to help grow the next generation of researchers, and I don’t think behaving as if we’re on Twitter is going to get us there.

If you’re reading this and recognise your own words: shame on you. And also, thank you. Bearing in mind that others in the target audience may be unfamiliar with evaluation, you did give us pause to consider whether we’d sufficiently explained the principles of our approach, before submitting the article to a different journal.

Reviewer 2 memes - enjoy

Scriven M. (1980). The logic of evaluation. Edgepress.

Davidson EJ. (1995). Evaluation Methodology Basics: The Nuts and Bolts of Sound Evaluation. Sage.

Schwandt T. (2015). Evaluation Foundations Revisited: Cultivating a Life of the Mind for Practice. Stanford University Press.

Fournier DM. (1995). Establishing evaluative conclusions: A distinction between general and working logic. New Dir Eval. (68):15–32.

Gargani J, King J. (2024). Principles and methods to advance value for money. Evaluation. 30(1):50–68.

Patton, M.Q. (2008). Utilization-Focused Evaluation. Sage.

Yarbrough, D. B., Shulha, L. M., Hopson, R. K.,& Caruthers, F. A. (2011). The program evaluation standards: A guide for evaluators and evaluation users (3rd ed.). Sage.

This is a great post.

I am particularly intrigued by the quote: "Consistent with this interpretation, interventions do not possess inherent value; rather, people assign value based on their perspectives and experiences". This seems to be the heart of the matter, and the root of reviewer 2's disagreement with the approach.

Thus it seems that the disagreement is not only methodological but also 1) rests on differences of ontology, and 2) reflects very different views on what the purpose and relevant research (evaluative) questions of a study might be...?