Eco-systemic frames in medical research (and evaluation)

A review of Sturmberg, Martin, Tramonti & Kühlein (2024)

Imagine a patient sitting in a doctor’s office, not only dealing with diabetes, but also depression, addiction, family pressures, and financial worries. Can a typical clinical research study guide the doctor’s next move? According to a thought-provoking article I came across, the answer is often no. A key reason is that these studies often focus on isolating the effect of one treatment on one problem, whereas real patients have lots of things going on at once. The authors argue that clinical research needs a more holistic approach to better help doctors help their patients.

Sounds like there might be some parallels with program evaluation. Journal club time, anyone?

Here’s the abstract:

Many practicing physicians struggle to properly evaluate clinical research studies – they either simply do not know them, regard the reported findings as ‘truth’ since they were reported in a ‘reputable’ journal and blindly implement these interventions, or they disregard them as having little pragmatic impact or relevance to their daily clinical work. Three aspects for the latter are highlighted: study populations rarely reflect their practice population, the absolute average benefits on specific outcomes in most controlled studies, while statistically significant, are so small that they are pragmatically irrelevant, and overall mortality between the intervention and control groups are unaffected. These observations underscore the need to rethink our research approaches in the clinical context – moving from the predominant reductionist to an eco-systemic research approach will lead to knowledge better suited to clinical decision-making for an individual patient as it takes into account the complex interplay of multi-level variables that impact health outcomes in the real-world setting.

Sturmberg, J.P., Martin, J.H., Tramonti, F., Kühlein, T. (2024). The need for a change in medical research thinking. Eco-systemic research frames are better suited to explore patterned disease behaviours. Frontiers of Medicine. Jun 3:11:1377356. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2024.1377356. eCollection 2024.

I won’t repeat what the paper says - it’s open access and a quick, worthwhile read - but I will offer my own reflections.

A scenario

Meet Max, a kid who lives near you. Max has asthma. He also gets anxious at school, and sometimes his family can't afford healthy food. A regular clinical study might look at one asthma medicine and test whether it helps kids like Max breathe better.

But that study wasn’t designed to help doctors address the specifics of Max‘s situation, like: Does the medicine make Max’s anxiety worse? What if he can’t take it properly because of stress or food issues? What if the root cause is actually damp and mould in his home?

The doctor is familiar with the research on the asthma drug, but it doesn’t offer guidance on Max’s circumstances. The consult is only six minutes long, so the doctor writes a script for the asthma medicine and books a follow up appointment to see how it’s going in a few weeks. There isn’t time to address the other issues today but perhaps they’ll come up on a future visit. Or not.

The paper argues that more clinical research should inform practice by taking a holistic view, rather than focusing on one problem at a time.

Of course, some researchers, doctors, nurses and other health professionals are already very good at integrative approaches - reflecting culturally-grounded ways of working, involvement in local initiatives, or individual practitioners’ professional interests in holistic medicine. For example, in my home of New Zealand, there are many Māori and Pacific-led health services that routinely approach healthcare from a whole-person, whole-family perspective. Systemic approaches have also developed at district level, two examples being WHIRI in the Waikato and Health Pathways, pioneered in Canterbury and spreading around the world.1

Nonetheless, the biomedical model continues to dominate clinical research, reflecting the prevailing philosophy of science underpinning it. There’s a need to balance reductionist approaches with more eco-systemic research, to guide integrated practice and support its adoption at scale, so that patients like Max can receive more holistic evidence-based healthcare.

Balancing reductionist with eco-systemic research approaches

A lot of clinical research is shaped by positivist traditions that emphasise controlled experimentation, “objectivity”, and standardisation. These methods have brought important insights, particularly in establishing cause-and-effect relationships. But their strength is also a limitation. They can constrain what questions get asked and influence assumptions about what counts as ‘good evidence’.

In the real world, health outcomes emerge from complex, interacting biological, social, cultural, psychological and environmental factors. Studying one element in isolation can establish a relevant causal relationship but isn’t a good way to understand how actual health decisions unfold in practice.

Mechanistic research asks, Does X cause Y? For example, Does this drug reduce blood pressure? Mechanistic models can simulate some interactions between genetic, environmental and other factors, but often fall short in capturing emergent behaviours within open, adaptive systems - like real people in real contexts.

Eco-systemic research shifts the lens. It asks questions like, How does this treatment fit into daily life? Does it work differently for people with co-existing conditions? What happens in different settings? These approaches combine clinical data with lived experience, practitioner insight, and system-level factors. This broader perspective is important for making informed personalised care decisions in complex, everyday clinical settings.

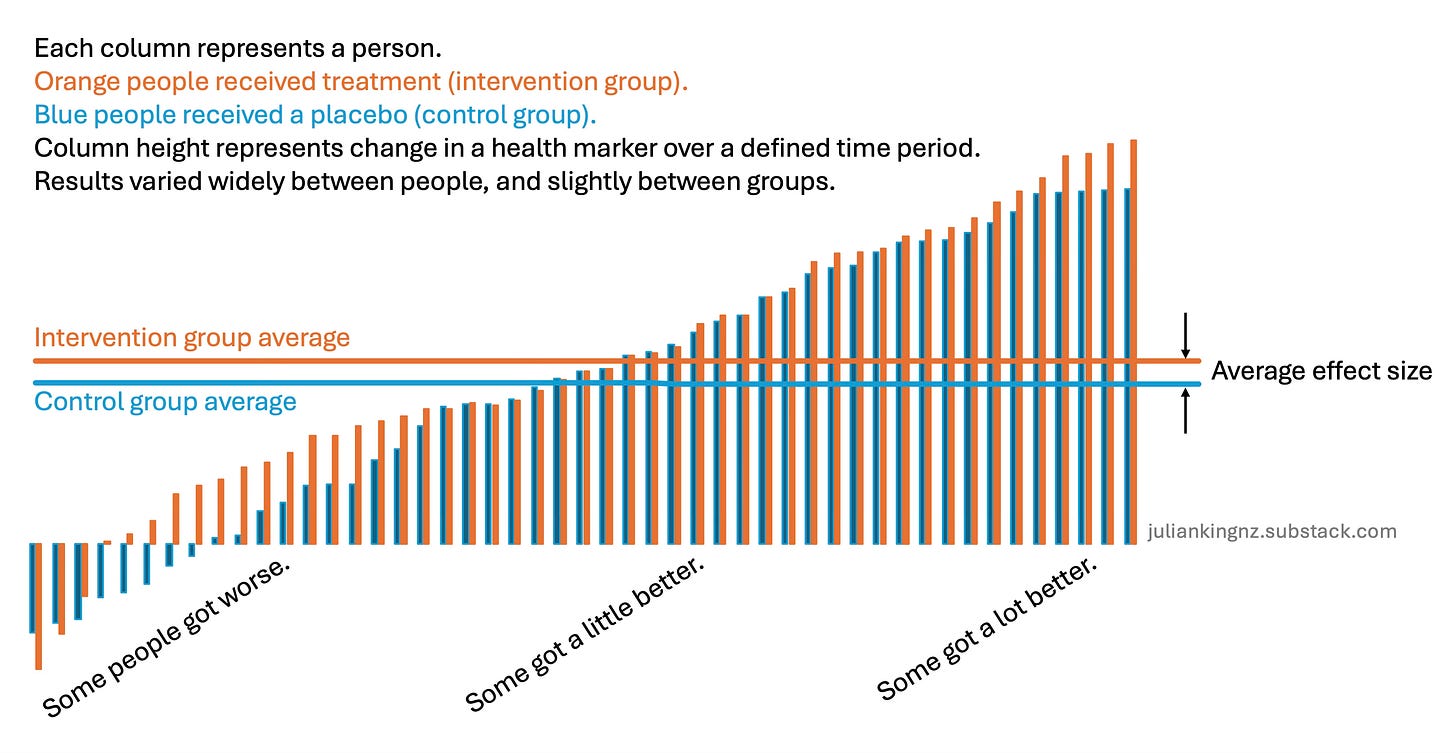

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are valued for reducing bias and isolating treatment effects.2 But real-world results are rarely uniform. An intervention doesn’t have the same effect on all patients. Some may get a lot better, some a little. Some might not experience any clinically significant change. Some might get worse. The following picture uses fictitious numbers to illustrate the sort of pattern often seen. This heterogeneity is observed every day in RCTs (and can be explored analytically3) but is often overshadowed by the average effect size and tests of statistical significance.4

Eco-systemic research pays attention to this variation, exploring patterns across age, gender, comorbidities, and care settings. It seeks to understand not just whether something works, but how, why, and for whom. This perspective doesn’t compromise causal inference - it deepens it. By recognising that causes operate differently in different contexts, research can inform more precise, equitable, and patient-centred care.

Traditional research often focuses on outcomes that are easy to measure like blood pressure, lab results, or hard endpoints like mortality. But these metrics aren’t always good indicators of experienced health and wellbeing. The authors call for a broader view of what counts as a meaningful outcome. For example: Can the person return to work? Sleep better? Manage pain well enough to enjoy daily life? Engage in family or cultural life?

These sorts of outcomes may be harder to count but are central to people’s experience of health. To measure what matters, researchers need to:

Involve patients, practitioners, and communities in defining outcomes.

Use tools that capture complexity, like narrative data, qualitative interviews, or multi-dimensional scales.

Recognise that different people value the same things differently, so average impacts and one-size-fits-all metrics aren’t enough.

Sounds like evaluation, eh?

There’s a lot in this paper that ought to resonate with people who evaluate policies and programs. Many of us are involved in similar battles in our daily work, to promote acceptance of complexity-informed approaches, methodological pluralism and inclusive rigour.

One of the key takeaways is that what happened on average doesn’t predict what will actually happen for the next person, the next program, or the next community. Causes and effects are rarely linear or singular. They’re multiple, interdependent, and shaped by contextual factors. Though there may be pressure to deliver evaluations that gift-wrap straightforward, replicable, scalable solutions that “work”, reality defies this wish. Transferring learning to new contexts is a complex, adaptive, principles-based process. Clinical researchers and program evaluators alike face the challenges the paper identified, of “learning to cope with uncertainty” and “embracing the inherent complexities” in the interventions they study.

What we sometimes dismiss as "noise" - the variability that doesn’t fit our models - contains real information about real people. The challenge is not to eliminate the noise but to get smarter at understanding the signals within it. Instead of focusing on generalisable, forever-and-always causal relationships, possibly a more useful aim for evaluation is to “provide critical contextual interpretation of new data“, as the authors put it.

That doesn’t mean abandoning reductionism altogether. Isolating causes and effects is valuable, especially when we’re transparent about the limitations and assumptions involved. While the article critiques the weight given to a narrow range of methods, it’s also important to acknowledge the strengths of well-designed experimental research. For instance, RCTs will continue to be helpful for studying efficacy and safety of some interventions. At the same time, research and evaluation can benefit from taking a more holistic and adaptive view that seeks to understand the complexity of human systems and recognises that interventions don’t operate in isolation - they’re embedded in relationships, institutions, cultures, histories, and other contextual factors. The challenge is perhaps in integrating both perspectives.

I think clinical medicine and program evaluation are both overdue to retire dogmatic “hierarchies of evidence” and simplistic slogans like “what works”. A more useful and honest line of inquiry is, how do interventions work in the real world, for whom, and in what circumstances? There are already well-established approaches (like Realist Evaluation) that specialise in addressing those questions.5 Another useful re-framing is shifting evaluation from retrospective questions to proactive design and delivery support, with rapid assessments of logical validity and empirical grounding to enable adaptive management and collaborative decision-making. We have evaluation approaches (such as Developmental Evaluation) to take care of these questions too.

We also need to be clear about what we’re measuring and why. Just because something is easy to count, measure, or monetise doesn’t make it important. Conversely, outcomes that are harder to quantify - like trust, dignity, cultural sustainability, or a sense of agency - often matter to people affected.

That brings us to the critical question of value to whom? Understanding the merit and worth of a program or policy requires more than a set of performance indicators or a high-status approach to causal inference. It demands that we involve stakeholders - especially those whose lives are affected - in defining what matters and what good looks like. Evaluation, in this sense, is not just a technical task. It’s fundamentally moral and political, “a collaborative, social practice”.

In short, clinical research and program evaluation stand to benefit from mixed methods, mixed reasoning, complexity-informed approaches, and inclusive rigour, integrating diverse perspectives and methods.

Economic methods of evaluation, such as cost-benefit, cost-effectiveness and cost-utility analysis, are well suited to evaluating costs and consequences of interventions studied with experimental designs. As we let in more complexity, these economic methods can start to struggle. That’s OK - there are ways of navigating this challenge.

The challenges aren’t just conceptual - they’re practical and political

The article makes solid points about why a paradigm shift should help to improve patient care, but leaves me wondering what whole-system changes would be needed and how these shifts could happen. How could systems of research, funding, policy, and healthcare delivery change to support eco-systemic evidence and learning? There’s a lot to unpack, but here are some examples:

How can medical practitioners be convinced of the validity and value of more complexity-informed ways of thinking?

What strategies or tools could be implemented to help them navigate the complexity without overwhelming their already demanding workloads?

What other structural issues hold back eco-systemic research and how can they be addressed?

Much medical research is carried out by, or on behalf of, companies that ultimately need to profit from the research to make it viable. This private market model aligns with reductionist, mechanistic research centred on proving the effectiveness of one product to address one problem. In contrast, I suspect eco-systemic research is a public good, requiring public funding to address systemic market failures in research.

Still, it’s encouraging to see increasing interest in complexity-informed ways of developing, evaluating and guiding clinical practice, like this and this.

Conclusion

The paper by Sturmberg et al. (2024) challenges a dominant paradigm in clinical research. Evaluators have long wrestled with similar tensions - rigour vs. relevance, generalisability vs. specificity, measurability vs. meaning, independence vs. involvement, evidence-based practice vs. practice-based evidence. The paper’s calls for methodological pluralism, inclusive definitions of value, deeper engagement with lived experience, and methods that are not just technically sound but ethically and socially responsive, echo principles that underpin good evaluation practice (IMHO).

Complexity isn’t a barrier to good science, it’s a reality to embrace. Our methods need to be flexible enough to hold complexity, learn from it, and respond to it with care. Sounds to me like medicine needs evaluative thinking.

What else do you see?

Here’s the paper. How does it affect you? What might evaluators and clinical researchers learn from each other? Let me know in the comments.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to Associate Professor Brad Astbury for very helpful peer review. Any errors or omissions are my responsibility. The opinions expressed in this post are mine alone and don’t represent those of any organisations I work with.

Thanks for reading!

I mention WHIRI and Health Pathways because by work has brought me into contact with both initiatives. There are many others.

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) can be designed to address several kinds of bias that threaten the internal validity (accuracy of causal inferences within the study) of clinical research findings. These include selection bias (skewed sample selection), performance bias (unequal treatment between groups), detection bias (differential outcome assessment), and attrition bias (skewed results from unequal dropout). These biases are addressed through randomisation (assigning participants to treatment and control groups randomly) and blinding (concealing treatment and control group assignments from participants and researchers). However, RCTs don’t eliminate all biases. Threats to external validity (applicability beyond the study to real-world populations) include contextual variability in factors like healthcare settings, eligibility criteria, intervention protocols, patient adherence and other things that aren’t replicated outside trials.

To pre-empt accusations of strawmanning: RCTs can investigate heterogeneity through various methods such as subgroup analyses, risk-stratified analyses, random-effects models, and statistical tests for heterogeneity. These approaches enhance the usefulness of clinical trials by identifying which subgroups derive the greatest or least benefit from an intervention. However, they don’t replace qualitative research, which goes deeper into understanding underlying mechanisms like the “how” and “why” behind observed effects.

There’s also a body of literature on “pragmatic trials” designed to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions in the real world, which the paper doesn’t dig into. The main goal of pragmatic trials is to determine the effectiveness of interventions under conditions that reflect everyday clinical care, with a view to maximising the generalisability and applicability of the results to typical practice.

The authors didn’t cite Ray Pawson’s foundational work on Realist Evaluation, nor his latest book, How to Think Like a Realist, which is surprising given their interest in understanding patterns in heterogeneous outcomes and the “complex interconnected and interdependent one-to-many cause-and-effect dynamics impacting people’s health”.

The reductionist approach to health research has never sat well with me when it comes to the reality of patient's lives. I recognise RCT's are important for drug trials etc, but I shudder when I hear 'evidence based practice' in a clinical setting - when the probability is that it has failed to acknowledge all of the issues raised here. Additionally, the history of medical research is such that many of the studies that have informed current practices were conducted primarily on male bodies... so the very foundations of so called 'evidence' are evidence for an average male (usually white US college student). It is well overdue that diversity AND complexity are better embraced in evaluation and knowledge generation.

Excellent article, Julian. One of the main reasons I subscribe to this substack is how you find tools and approaches from other disciplines and unpack the crossovers to evaluation.

Using more system thinking and tools of pattern recognition will advance both medical research and evaluation. However, I'm disappointed that the authors of the original article misappropriate and make so much use of the term "ecosystem". Unfortunately, we have taken a very important concept describing how nature and environmental issues affect society and turned it into a near-meaningless buzzword' Business, politics, technology, the arts-- you name it, they all have an "ecosystem". My eyes glaze over now when I see it used. So, while the original article made some good points, the multiple references to ecosystems lowered its value materially.

My advice as you continue to build and improve the framework, is to find an evaluation-appropriate way to describe (brand?) the interconnectedness of factors and influences and how we think about them.