Value propositions (Part 2): clearing the path from theory of change to rubrics

The case of the NZ Ministry for Regulation

Last week, I shared a presentation that Adrian Field and I gave at the Australian Evaluation Society (AES) Conference on Friday, 20 September to demonstrate how value propositions can help clear a path from a theory of change to rubrics. With roving mics (thanks Amanda Hunter!), we engaged the audience in developing a value proposition for a newly established central agency of the New Zealand government, the Ministry for Regulation. Today, I’m going to unpack the Ministry’s value proposition as an illustrative example. This also doubles as a report-back to those who attended our session last week.

Quick recap

In our evaluation work, we often co-create rubrics with stakeholders, establishing an agreed basis for making warranted evaluative judgements from the evidence we collect and analyse.

A theory of change or program logic can be a useful precursor to developing rubrics, guiding considerations about what aspects of a program the evaluation will focus on. However, it can feel like a conceptual leap getting from a theory of change to a set of value criteria. This challenge arises because change and value are different things.

Theories of change include a set of propositions about how organisational actions might lead to impacts, but they aren’t always explicit about value - the merit, worth or significance that people and groups may place on the impacts, the organisational actions, and the resources invested. To bridge this gap, we can articulate a program’s value proposition, explaining why the program may be worth investing in, on the basis of the value it promises to add.

By explicitly considering value, we can enrich a theory of change and develop clearer rubrics. In our presentation, we argued that defining a program’s value proposition is both useful and fairly straightforward, and that the first step is to describe the value in words.

Here’s the earlier article for extra background and key presentation slides.

Example: The Ministry for Regulation

The following example is intended to illustrate what a value proposition looks like. It incorporates insights from participants in our conference session. It also builds on a ‘cheat sheet’ that I prepared before the session. We wanted to be ready with a set of prompts in case we needed to nudge the roving mic conversation along. But it was unnecessary - turns out a room full of evaluators doesn’t need any nudges to get started!

Background

Regulations promote fair play and safeguard our wellbeing in areas as diverse as healthcare, workplace safety, financial markets, and transport. At the same time, they impose compliance costs. Proposed regulations are subjected to impact analysis to ensure they add worthwhile value. Nonetheless, the cumulative effect of multiple regulations (even good ones) can impede economic activity.

NZ has recently established a new Ministry for Regulation, with the aim of ensuring regulations deliver value to society. Here’s a simplified, unofficial logic model we developed and presented for the exercise of brainstorming the Ministry’s value proposition.

For a more comprehensive look at the Ministry’s context and purpose, check out the Ministry’s website and this article from Asymmetric Information, the Substack newsletter of the NZ Association of Economists (NZAE).

Value proposition questions

The reason for articulating a value proposition is to help us think clearly and systematically when we develop a set of context-specific value-for-money (VfM) criteria, focusing on critical factors that affect whether a policy or program (in this case, the Ministry for Regulation) will create a lot of value or a little. Accordingly, the value proposition questions are designed to prompt consideration about what it would look like for the Ministry to be a good steward of resources, deliver its outputs productively, achieve outcomes, create enough value and do so equitably.

The Five Es (economy, efficiency, effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and equity) aren’t the definitive set of VfM criteria (there’s no such thing) but they’re a good checklist for canvassing potential aspects of good resource use. More on that here.

Perplexity and me

My starting point for developing our cheat sheet was a conversation with a Large Language Model (LLM) called Perplexity, in which I described the Ministry and asked it the value proposition questions from the image above.

One of the features of Perplexity is that (unlike ChatGPT) it accesses the live internet and can draw on up-to-date information in response to prompting. However, it is not always very discerning about which sources it uses, and this can affect the quality of its analysis.

As always, I need to stress that these so-called “artificial intelligence” (AI) apps can’t and mustn’t replace collective human deliberation. However, they can help with a rapid start to brainstorm potential elements of a value proposition.

To develop the cheat sheet, I sense-checked, prioritised and summarised points from Perplexity’s output, adding a few extra thoughts of my own and drawing on the NZAE article I mentioned above. Finally, after the session, I added participants’ input. The following value proposition is an amalgam of all of these sources.

A few caveats

Bear in mind that the purpose of this value proposition is illustrative, showing how a set of questions can prompt ideas about value that can help inform criteria development. If this were a real evaluation, the value proposition would need more work including review and input from the Ministry, regulatory experts and stakeholders.

The following analysis is apolitical; for illustrative purposes we are focusing on what could be, without judging the likelihood of these aspects coming to fruition.

You are welcome to critique the content of this draft and suggest enhancements. I’m sure it is far from perfect.

A draft value proposition for the Ministry of Regulation

1. To whom is the Ministry for Regulation valuable? How is it valuable to them?

The Ministry could (potentially, if well designed and implemented) be valuable to:

Businesses and entrepreneurs: Reducing regulatory red tape; reducing barriers to innovation and growth by addressing regulations that are superfluous or not working effectively; simplifying and clarifying regulations, making compliance easier and lower-cost.

General public: Improved regulatory quality, leading to better public policy outcomes; potential economic benefits from increased business productivity, competition and innovation; more transparent and accountable regulatory processes; protection from negative externalities and risks.

Māori and Treaty of Waitangi partners: Improved engagement with Māori in regulatory design processes; ensuring regulations consider and respect Māori interests and perspectives.

International stakeholders: Enhancing NZ’s reputation for good governance and regulatory practice; improving the ease of doing business in NZ for foreign companies.

Government agencies: More effective regulatory systems and regulations.

Public servants: Raising the capability of those who design and operate regulatory systems; providing guidance on good practices in regulatory stewardship.

Additionally, participants noted that there could be trade-offs between value to different groups. For example, businesses may value reducing regulatory red tape while the general public may favour extra regulatory protection. Government might prioritise efficiency while disadvantaged groups may place greater value on equity.

2. What kinds of resources are invested in the new Ministry, by whom? What does good stewardship of those resources look like?

Financial resources: The Ministry is funded in part from savings generated by closing the Productivity Commission. This raises an interesting question about opportunity cost: in general, when conducting economic evaluations and VfM assessments, we are interested in how an investment compares to its next-best alternative(s). When considering the impact and value of the Ministry of Regulation we could consider how it compares to the Productivity Commission.

Other resources: It takes more than just money to create an effective Ministry for Regulation. Some of the other resources that need to be well-managed and marshalled to ensure the Ministry creates value include:

Political capital, including stakeholder and cross-party buy-in to the Ministry’s remit.

Relationships, communication and trust with agencies across the state sector and other stakeholders (additionally, participants noted the investment of time it may take to build these relationships).

Human resources: an effective team to carry out the Ministry’s functions.

Good stewardship of resources includes considerations such as:

Strategic resource allocation: aligning staffing and budget with the Ministry’s key functions; ensuring efficient use of resources transferred from other agencies.

Internal capability: building and leading a cohesive, high-performing Ministry team with regulatory expertise and good knowledge of the regulatory environment.

Cultural competence: developing capability to engage with Māori, Pacific and other communities and to understand their perspectives; promoting diversity and inclusiveness within the Ministry.

Fiscal responsibility: economical use of allocated budget.

Accountability and transparency: regular reporting on the Ministry’s performance and impact; regular information releases about the Ministry’s activities.

3. What ways of working could maximise value from the Ministry for Regulation?

Collaborative approach: Collaborating as partners and doing work with (not to) other government agencies; developing effective mechanisms to engage with stakeholders across public and private sectors on systemic issues.

Evidence-based decision making: Conducting robust regulatory reviews across sectors; using systematic impact and risk analysis when assessing regulatory changes; monitoring and reviewing existing regulatory systems to determine if they remain fit for purpose.

Strategic prioritisation: Focusing on sectors that have the greatest impacts on wellbeing and productivity; identifying regulations that are superfluous, ineffective, or could be improved; identifying and addressing problems, vulnerabilities, and opportunities for improvement in regulatory systems.

Capability building: Developing agencies’ regulatory stewardship and regulatory practice capability across the state sector.

Do no harm: Participants talked about the importance of identifying solutions that do not compromise safety.

4. What changes might we see in the short-to-medium term, that would help us gauge whether the Ministry for Regulation is on track to create longer-term value?

For reasons of time, this question was not covered in the presentation. However, examples of the kinds of outcomes that could be evaluated include:

Improved quality of regulatory impact assessments: Increase in percentage of RIAs meeting quality standards; reduction in the number of regulations implemented without adequate impact analysis.

Regulatory burden reduction: Outdated or ineffective regulations identified and removed, and their significance; reduction in compliance costs for businesses and individuals in reviewed sectors.

Increased regulatory capability across government: Improvement in regulatory skills for relevant personnel.

Stakeholder engagement and satisfaction: Increase in the number and diversity of stakeholders engaged in regulatory consultations; improvement in stakeholder satisfaction ratings regarding regulatory consultation processes.

Transparency and accessibility of regulatory information: Improvement in dissemination of clear, publicly available explanations of regulations’ purposes, costs and benefits; increased public understanding of regulations.

Cross-government collaboration: Quality of inter-agency collaborations on regulatory issues; improvement in coordination between regulatory bodies.

Economic indicators: Reduction in regulatory compliance costs as a percentage of GDP; improvement in NZ’s ranking in international regulatory quality indices.

Public trust and confidence: Increase in public trust ratings for regulatory systems; improvement in business confidence related to regulatory environment.

Regulatory impact on specific outcomes: Improvements in relevant social, environmental, or economic indicators in sectors where regulations have been reviewed or updated.

5. To whom, and how, might the Ministry for Regulation affect equity, fairness, or level the playing field?

For businesses: By identifying and addressing regulations that are superfluous or not working effectively, the Ministry could help create a more equitable regulatory environment for businesses of all sizes; simplifying and clarifying rules could make compliance easier, potentially levelling the playing field between large companies with more resources and smaller businesses.

For disadvantaged groups: The Ministry's work on improving regulatory quality could lead to better public policy outcomes, potentially addressing inequities faced by disadvantaged populations.

For Māori: By ensuring regulations consider and respect Māori interests and perspectives, the Ministry could help promote more equitable outcomes for Māori communities.

For consumers: Enhanced consumer protection through well-designed regulations could help ensure fairer treatment of consumers across different markets and sectors. Additionally, participants noted that reducing red tape could facilitate more consumers getting services they need.

For the public sector: By raising the capability of those who design and operate regulatory systems, the Ministry could help create more consistent and fair regulatory practices across government agencies.

For international stakeholders: Improving the ease of doing business in New Zealand could create a more level playing field for foreign companies looking to operate in the country.

For different sectors: By conducting regulatory reviews across sectors, the Ministry could identify and address inequities or unfair practices within specific industries.

Equity (and other considerations like freedom, safety and privacy) may conflict with efficiency and productivity, necessitating trade-offs when designing good regulations and regulatory systems. Participants also cautioned that equity could be negatively affected if an ‘equal treatment’ lens is applied.

6. What factors might affect whether the investment in the Ministry for Regulation creates a lot of value or a little? (i.e., priority aspects of performance to evaluate)

Political support: Sustained commitment from the government to regulatory reform; willingness of other ministers and departments to cooperate with the Ministry's initiatives.

Quality of leadership and staff: Expertise and effectiveness of the Chief Executive and key personnel; ability to attract and retain skilled regulatory professionals.

Methodology and approach: Robustness of the analytical frameworks used for regulatory impact assessments; effectiveness of the review process for existing regulations.

Stakeholder engagement: Success in building constructive relationships with businesses, industry groups, and other stakeholders; ability to gather meaningful input from affected parties

Implementation capacity: Resources allocated for implementing recommended changes; cooperation from other departments in executing regulatory reforms.

Outcome evaluation: Development of clear criteria and metrics to assess the impact of regulatory changes; ability to demonstrate tangible benefits to businesses and the public.

Adaptability: Flexibility to adjust strategies based on feedback and changing economic conditions; capacity to address emerging regulatory challenges in new sectors.

Transparency and accountability: Regular reporting on the Ministry's activities and achievements; openness to external scrutiny and evaluation of its performance.

Coordination with existing structures: Effective integration with existing regulatory bodies and processes; avoiding duplication of efforts or conflicts with other government entities.

Economic context: The overall regulatory burden on the economy at the time of the Ministry's establishment; potential for regulatory improvements to stimulate economic growth.

Time needed for system transformation: Participants noted that it would take time for value to be realised, including time for storming and norming, and changing the language of regulation.

What next?

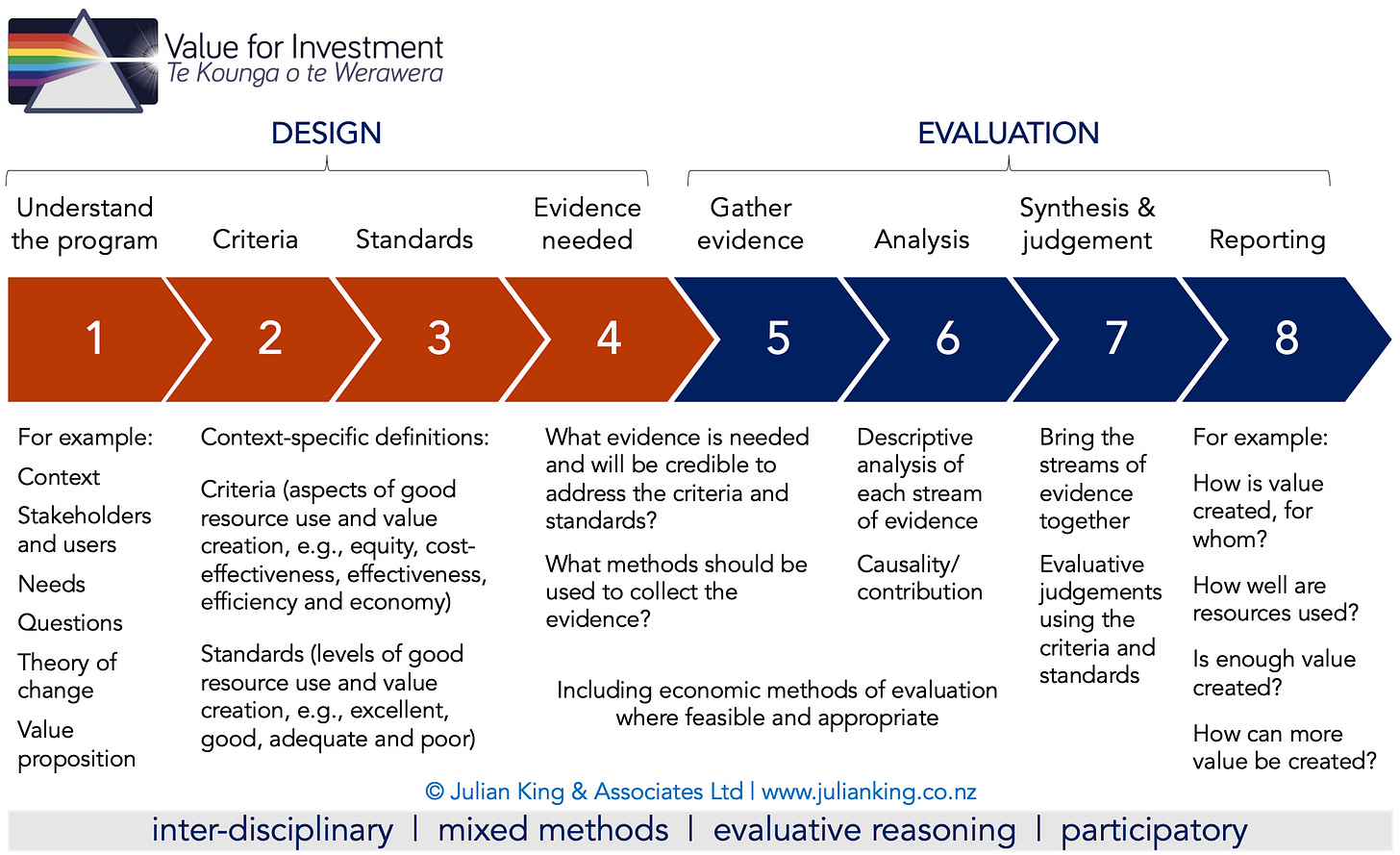

If this was a real evaluation, describing the Ministry’s value proposition would be part of Step 1 in the following 8-step process to get from value-for-money questions to evaluative conclusions.

The next step would be to develop criteria. Indicatively, if developing bespoke definitions of the 5Es, the considerations above would have helped to surface critical, observable factors that could tell us whether the Ministry is on track to create value. As this case illustrates, developing a value proposition encourages us to think more broadly than simplistic input/output/outcome ratios, getting to the heart of what it would take to create value through good resource use:

Cost-effectiveness: Creating enough monetisable value to justify the fiscal costs of the Ministry; creating value (tangible or intangible) for businesses, entrepreneurs, general public, Māori and Treaty partners, international stakeholders, government agencies, and public servants. The cost-effectiveness assessment could contextualise the value created by the Ministry compared to the Productivity Commission, bearing in mind the economic context and potential for regulatory improvements to stimulate economic outcomes.

Equity: Reducing inequities affecting businesses, disadvantaged groups, Māori, consumers, public sector, international stakeholders, and specific sectors.

Effectiveness: Political support, stakeholder satisfaction, improvement in RIA quality, regulatory burden reduction, increased regulatory capability, transparency and accessibility of regulatory information, public trust and confidence, regulatory impacts on specific sectors, impacts on economic indicators.

Efficiency: Collaborative approach; coordination with existing structures, evidence-based decision making; strategic focus on improving regulation; strategic prioritisation; capability building, methodology and approach, implementation capacity, adaptability.

Economy: Strategic resource allocation; internal capability; cultural competence; fiscal responsibility; accountability and transparency.

Reminder: If this were a real evaluation, the value proposition and criteria would need more work including review and input from the Ministry, regulatory experts and stakeholders. This case is for illustrative purposes only. You are nevertheless welcome to comment.

Don’t be like Christopher Robin

I don’t recommend using Perplexity in real-world evaluations because (among other things) we mustn’t enter confidential information into public LLMs. We also need to stay vigilant to the potential for errors and biases including fabrication of plausible-sounding but completely fictitious answers.

There’s a risk in using Perplexity to brainstorm a value proposition (or anything else), nicely encapsulated in the following poem by AA Milne. If Christopher Robin isn’t sure, he asks Winnie The Pooh, with the logic that “if he’s right, I’m right, and if he’s wrong, it isn’t me”. This nicely insulates Christopher from taking responsibility, but nothing good can come of it in an evaluation. Don’t be like Christopher!

Also see

Field, A., King, J., Moss, M., Parslow, G., Schiff, A., Chianca, T.K., Chianca, G., Mattiello, C. (2024). Urban 95/Ateliê Navio Value for Investment evaluation. Report for Van Leer Foundation. Dovetail Consulting Limited, Auckland.

King, J., Namukasa, E., Hurrell, A. (2023). Incorporating value creation in a theory of change. The Evaluator, Spring 2023, 6-9.

King, J. (2021). Expanding theory-based evaluation: incorporating value creation in a theory of change. Evaluation and Program Planning, Volume 89, December 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2021.101963.

Where’s this?

If you’re the first person to correctly identify the vantage point from which this photo was taken, and tell me in the comments below, I’ll shout you a 12-month subscription to the full Evaluation and Value for Investment archive.

Love the cautionary tale courtesy of Christopher Robin.

My internet sleuthing has led me to conclude it's in Auckland, either on a ferry or near Hamer street ferry terminal, looking towards Stanley Point...?