Exploring value in the context of social investment

Social investment brings together different perspectives and ways of measuring value across social, economic and cultural domains. Doing it well requires integrated efforts across disciplines.

I recently joined a panel discussion with Atawhai Tibble, moderated by Angie Tangaere of the Auckland Co-Design Lab, jointly organised by the Auckland Co-Design Lab, Mā Te Rae Māori Evaluation Association, and Healthy Families Far North. Many thanks to Debbie Goodwin for inviting us to join the panel, to the organisers and all those who participated.

Angie invited us to reflect on the following questions:

How do we determine “value” and who gets to decide?

What kinds of evidence can we use to determine and measure different forms of “value”?

How does an economic cost-benefit analysis sit with a whānau (family)-centred view of value? What tensions arise, and how can these be reconciled?

In this post, Atawhai and I share some key points from our conversation, plus a few extra thoughts that occurred to us since (so it’s not verbatim, it complements the video which is also available at the end). The conversation was expertly recorded by graphic design artist Dylan Culhane:

The difference in terminology between a social return on investment and the government’s social investment approach

Julian:

Social return on investment (SROI) is a method used around the world for estimating how much social value an organisation or program creates. It has eight guiding principles which include working with stakeholders to understand what’s valuable, and doing something pretty similar to cost-benefit analysis by measuring costs and benefits in units of money to see if the value of the benefits outweighs the costs.

The social investment approach is the current New Zealand Government’s approach to making evidence-based decisions. Instead of viewing a social service or program as a cost, we can view them as investments, with the idea that if we invest in the right things at the right times, we can create more value. This idea resonates for me.

Atawhai:

I’ve witnessed the evolution of the social investment approach first-hand, from its early days when I worked for the first CEO, Dorothy Adams. I was also quite close to the late Professor Richie Poulton. Now we have Social Investment 2.0.

What I notice is a real desire to focus on key things that will make a difference for vulnerable groups over the long term. Moreover, there is a sharp focus addressing the challenges in a more data-centred and evidence-based way. This focus on using data to understand what works, what doesn’t, and how we can achieve lasting change is quite fundamental.

How do we determine “value” and who gets to decide?

Atawhai:

Absolutely, that's the million-dollar question, isn't it? It's about going beyond good intentions and warm fuzzies. Commissioners want to see tangible results, feel the shift in whānau wellbeing, and witness communities becoming stronger. But they also want to see the impact in the long run. Not just at the end of a contract. And to do that, we need to embrace both the power of storytelling and the insightful lens of data.

Julian:

The starting point for me is to consider what is value? In practical terms, value is about he tangata (the people) because things don’t have value; people put value on things. Value is what matters to people about something, like a policy or program or service. And that means, to understand value, we have to engage with people. No matter how we measure value, we’re seeking to understand how something matters to people.

What kinds of evidence can we use to determine and measure different forms of "value”?

Julian:

Valuing things in dollars is one way. It’s surprising how many things we can value in dollars. It’s a valid thing to do and a useful way to communicate value. But valuing things in dollars is a choice - it’s just one way of doing it. Money can represent value, but money in and of itself isn’t value. And some things are harder to value in money than others.

Economists sometimes use non-monetary numbers to represent value too, like measures of wellbeing, and quality-adjusted life-years and other measures.

We can also describe value qualitatively. Like I could ask you (individually or as a group), tell me about the value of something, like a program or service. Why is it important to you? How is it important to you? Tell me a story about its value to you. This is actually a great starting point for exploring the value of something, in my experience: express the value in words. Then figure out how to measure it after that.

So dollars, numbers, description, stories - they’re all legitimate ways of exploring value. And we don’t have to pick just one. Using several together can be powerful.

Atawhai:

Some people may feel worried about a pure data focus. Is it less personal than the stories whānau give us? Are they asking us to ignore whānau stories? This is quite a black and white view of how to work with data and whānau.

My view is to think “AND”. Stories are like the heart of our mahi, they give us the 'why' and connect us to the human experience. But data is the backbone, providing structure, evidence. It helps us measure the impact of our actions, track progress, and see where we need to adjust our approach.

Together, data and stories hold ourselves accountable and ensure our efforts translate into real improvements in areas like health, education, and whānau wellbeing.

Plus, having solid data helps us make a strong case for continued funding and support, so we can keep the good work going.

How does this data fit with a Māori worldview?

Atawhai:

Does it seem kind of… Western? Not at all! Counting and measuring is woven into the fabric of te ao Māori, albeit in our own way.

For example, our tūpuna used a system of measurement based on the human body - finger widths, hand spands, and arm lengths - to precisely construct whare whakairo without the need for modern tools. And the stars were our measurement tools, serving as maps and compasses for those epic voyages from Hawaiki! So as fellow Hato Paora Old Boy, Prof Rangi Mātāmua said recently, “We had to use our science to get here to Aotearoa”.

Similarly, numbers and data can help us exercise manaakitanga! Let me share a memory from my childhood. Growing up on my marae at Te Tikanga, I remember my Aunty Mere, asking me to count the visitors. "Te Atawhai, tokohia ngā manuhiri?" she'd say, wanting to know how many mouths to feed. This is te ao Māori in action! It's using data to ensure everyone is cared for and that resources are used wisely.

From time immemorial, Māori have utilised data in innovative ways to address our unique requirements. Sir Tipene O’Regan aptly described us as Rapid Adapters. Throughout history, we have demonstrated our ability to thrive in new environments while placing emphasis on what truly matters. Consider the trading ships originating from the Bay of Plenty that sailed to Sydney, owned by hapū and provided sustenance for the people of New South Wales. Our people extended beyond being mere gardeners and warriors; we were traders and ship owners who skilfully navigated intricate economic systems. As Professor Rangi Mātāmua astutely observes, we didn’t sail from Hawaiki by fluke. We used the stars, our knowledge, and the data that was in front of us! We have always been scientists.

Let me give you some other examples of data being used to measure what matters to Māori. In recent times, two notable examples stand out in terms of integrating Māori cultural values into measurement and valuation.

I was directly involved in the development of the first-ever Māori wellbeing survey delivered by Stats NZ: Te Kupenga. Groundbreaking, it focused on things that matter to Māori like whānau wellbeing, Māori identity, pepeha, sense of tūrangawaewae or marae connectedness, and te reo Māori capability. The significance of this survey lies in its ability to measure elements that truly matter to Māori communities, thereby providing valuable insights into their unique experiences and perspectives.

Separate from this, Julian has contributed to Te Kounga o Te Werawera in collaboration with Kataraina Pipi, Nan Wehipeihana, Louise Were, and others. This initiative involved Māori researchers engaging in discussions and critically reflecting on methods and tools from economics and evaluation, through a Value for Investment lens. The aim was to ensure that evaluations adequately capture and reflect Māori cultural values and worldviews.

I’m optimistic that in the future, more and more of our people will contribute their cultural values to measurement and valuation. This will not only enrich our understanding of society but also lead to more equitable and inclusive outcomes for all New Zealanders.

What are the challenges with economic cost-benefit analysis to demonstrate value?

Julian:

Cost-benefit analysis (CBA) is a method that measures both costs and impacts in dollars, so we can directly compare them and see if the benefits exceed the costs - or in other words, see if a program creates more value than it consumes. I think that in evaluation, we could and should use CBA more often than we do. I also think there are many times when CBA wouldn’t be enough on its own.

For example, CBA tends to privilege those outcomes that are easy to count and measure and value in dollars. But some of the most valuable outcomes can be hard to value in dollars. For example, if we imagine a program that aims to reduce addiction and reduce crime, it’s easy to count the deficit stuff - the social harms of addiction and crime - and see if the program reduces those social harms. We might find that it reduces drug use and saves money for health services and police. But that might only be part of the value.

The program might also have other benefits, like increasing social connectedness, cultural identity, connections with Māori worldviews. But it’s hard to put dollar values on those things and we might accidentally lose sight of these kinds of benefits in a CBA. You might see them discussed in the text but if they’re left out of the dollar valuations, they’re left out of the benefit-cost ratio which is the part of the analysis that gets the most attention.

I recently co-authored a thinkpiece with Alex Hurrell in the UK that discusses strengths and limitations of CBA, and how to combine insights from CBA with other evidence and ways of valuing. Here’s a link to that document. Also check out this recent LinkedIn post by Jay Whitehead.

How can we demonstrate value when necessary data is unavailable? What new kinds of evidence do we need to build with whānau?

Atawhai:

We keep hearing about “outcomes” in social investment, and asking how would we know if we’re achieving them. That’s a crucial question. Outcomes are the real, tangible changes we’re striving for in the lives of whānau and communities. It’s about more than just delivering programs; it’s about creating lasting improvements in wellbeing, education, economic security, and social connectedness. To achieve these outcomes, we need a long-term vision, not just the short-term fixes. We need to invest in initiatives that build resilience, empower whānau, and address the root causes of social challenges. And crucially, we need a robust outcomes measurement framework that tracks progress, identifies what’s working, and guides our decision-making.

Building a good outcomes framework might sound complicated, but it doesn’t have to be. It starts with being crystal clear about what we're trying to achieve. What specific changes do we want to see in whānau lives? Once we've defined those outcomes, we need to identify the indicators that will tell us if we're moving in the right direction. These might be things like improved school attendance, increased employment rates, reduced reliance on social services, or stronger connections to culture. The key is to choose indicators that are meaningful to whānau and relevant to the outcomes we're aiming for.

So what role do non-government organisations (NGOs) play here? NGOs play a crucial role as trusted partners on the ground, working directly with communities and understanding their needs. They can help ensure that outcomes frameworks align with community aspirations and that data is used to drive positive change, not just for compliance. NGOs navigate funding complexities, ensuring initiatives are sustainable and impactful. Their expertise can enable ethical, culturally appropriate data collection, empowering communities. NGOs translate data into compelling stories, advocating for continued investment in effective initiatives. NGOs serve as champions in communities, bridging the gap between whānau and funders, and promoting ethical data management. They can act as trusted kaitiaki of information, ensuring its use uplifts communities and drives positive change.

Julian:

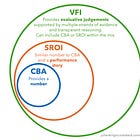

I developed an approach to address challenges with using economic tools alone to measure value. This approach combines insights from economics and evaluation. It’s called Value for Investment. It brings together a mix of evidence - economic, quantitative and qualitative - to enrich our understanding of value. It’s not another method and it doesn’t replace the methods and tools we already have. It’s a system to help get clear answers to value-for-money questions by walking you through a series of steps to:

Define what good resource use looks like in your program or service

Align the evaluation with the design and context of the program/service

Select an appropriate mix of methods to gather and analyse different kinds of evidence

Make robust, transparent evaluative judgements

Report findings clearly.

Bottom-line

Julian:

The methods and tools aren’t the value. Value is how something matters to people. Any time you need to demonstrate value, before you try to measure it, start by describing it. For example: Who is this policy or program or service valuable to? In what ways is it valuable to them? What would ‘enough value’ look like?

Then figure out what kinds of evidence you need. Might be dollars, might be numbers, might be qualitative evidence. Usually, we find it’s a mix. Stand back from return on investment alone and think about all the evidence we can use to unpack the value of a social investment.

I have a saying: give them what they want and give them what they need. In a sense it’s about speaking truth to power. Meet decision-makers where they are and provide the methods and insights they asked for - and, if we think those methods and insights have missed something important, provide the extra intel too.

Atawhai:

By weaving together stories and data, we can create a powerful force for change. Stories provide the heart, the human connection, and the inspiration. Data provides the evidence, the accountability, and the direction. Together, they create a compelling narrative that can move mountains. They can inspire funders, policymakers, and communities to work together to create a brighter future for our whānau. It's about recognising that both qualitative and quantitative information are valuable tools in our journey towards a more just and equitable society.

Links

Auckland Co-Design Lab: Link to the video, the visual, and other materials here.

Free Value for Investment resources via Julian’s website: www.julianking.co.nz

Looking very snappy in the graphic Julian: some added value :).