Value propositions and criteria: are free school lunches worth investing in?

A Value for Investment case study from Aotearoa New Zealand: The Ka Ora, Ka Ako program

Last week I detailed a strategy for developing contextually meaningful Value for Investment criteria by articulating the value proposition of an investment (e.g., policy, program, or intervention).

This week, a case example.

This briefing by Carolina Mejia Toro and Professor Boyd Swinburn from the University of Auckland outlines preliminary evaluation work on Ka Ora, Ka Ako, the free healthy school lunch program in NZ. It assesses the program’s performance against 21 criteria, providing a summative judgement and opportunities for improvement.

In this post I use the Ka Ora, Ka Ako evaluation as a case example, telling the story of how the team developed a value proposition and a set of criteria with stakeholders. In the words of the authors:

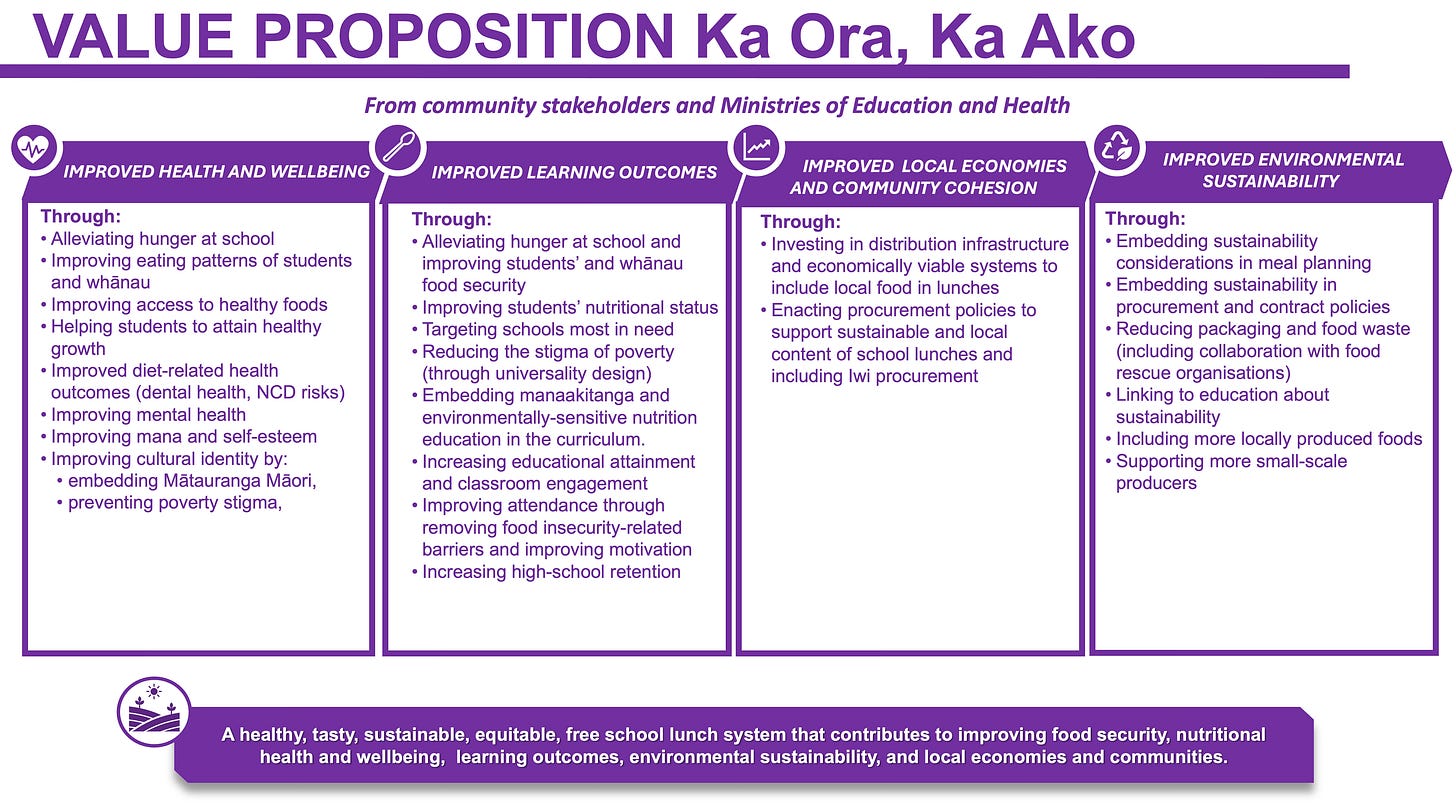

Value for Investment is a mixed-methods, participatory system that assesses how well resources are used and how much value is created. We gathered inputs from community and government stakeholders to identify what value they expect the programme to produce. From this value proposition, we created 21 criteria in five economic domains to measure those values and validated them with stakeholders. Next, we collected Ka Ora, Ka Ako evaluations and monitoring data to create an evidence base for each criterion. Programme performance (excellent, good, adequate, poor) for each criterion was made by the research team but has yet to be validated by stakeholders (Mejia Toro & Swinburn, 2024).

Step-by-step

The team followed the 8 steps of the VfI approach. If you subscribe to my Substack you’ll have seen this diagram before. In this post I zoom in on the value proposition (part of step 1) and the criteria (step 2).

Value proposition

Policies and programs can be regarded as investments in value propositions. When a decision-maker allocates resources to a program, they are investing in “a proposition about the value of a course of action”, as Andrew Hawkins put it. Value propositions are useful constructs because if we can define them, we can evaluate how well they’re met. In business, a value proposition is a declaration of intent that communicates the benefits of a product or service to customers. I think social programs should have clear value propositions too - though there’s extra complexity because the customers who receive the service and the customers paying for them are different groups, so questions of “value to/from whom?” and “who decides?” are critically important.

The evaluation team used a participatory approach to co-define the value proposition. To my mind, involving stakeholders is integral to good evaluation. When we set out to evaluate, we commit to making judgements about merit and worth. The judgements need to be warranted - supported by evidence and reasoning. The reasoning is assisted by explicit criteria and standards. The criteria and standards represent values - an expression of what matters to people. Determining which people - who should have power and who has a right to a voice - and involving them meaningfully in evaluation co-design and sense-making, are therefore fundamental to ethical and valid program evaluation.

To develop the program’s value proposition, the team engaged with community and government stakeholders in a series of workshops, to explore questions such as:

To whom is the investment valuable?

How is it valuable to them?

How is the value created?

The team consolidated and synthesised the feedback from stakeholders and created a draft value proposition. Stakeholders were invited to review and comment on the draft. Here’s the resulting value proposition:

Criteria

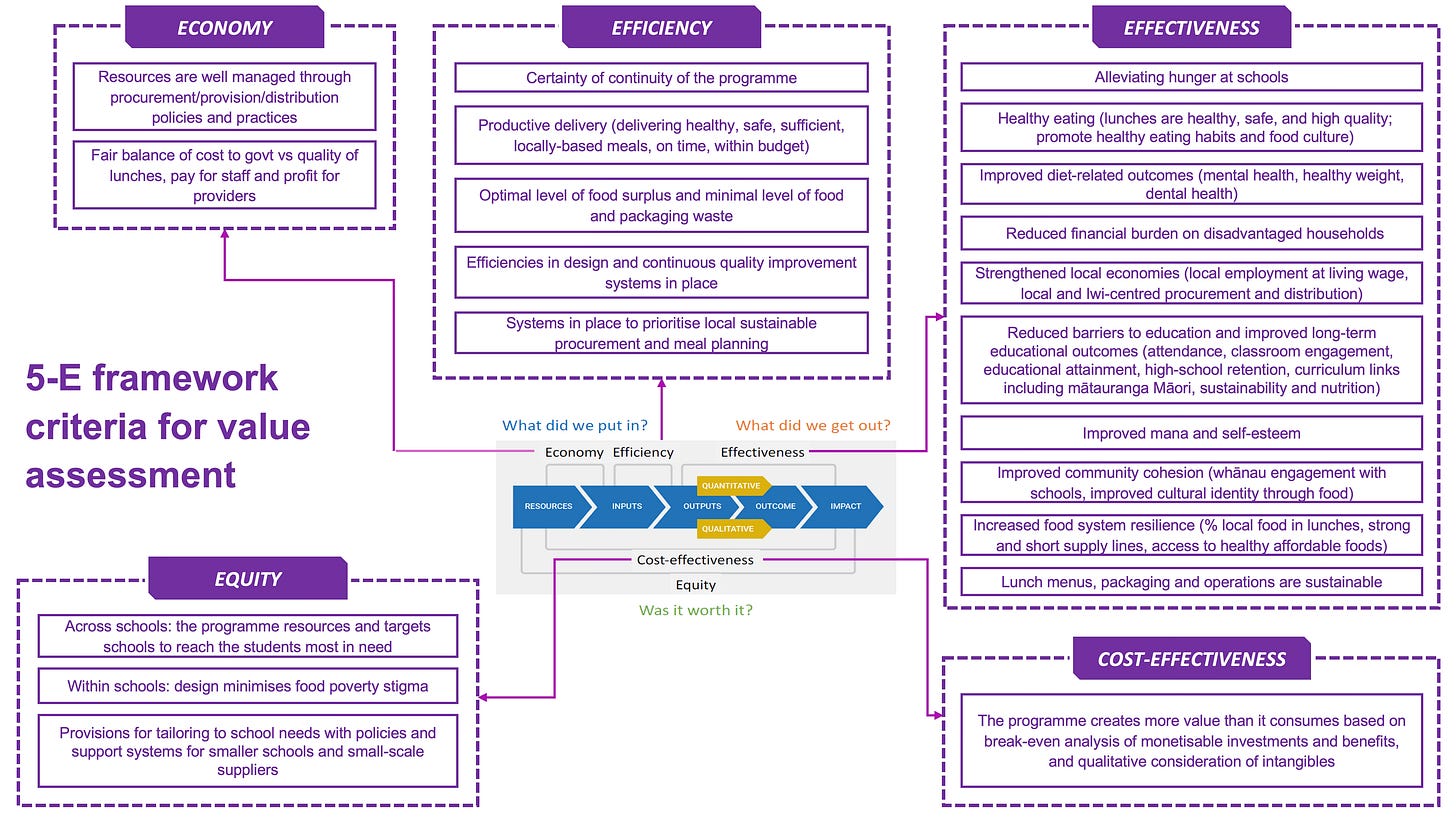

The next step was to identify critical, observable aspects of performance and value that would be the focal points for the evaluation. This involved further unpacking the value proposition to consider:

What resources are invested, and by whom? What does good stewardship of those resources look like?

What ways of working will ensure we get the most value from the resources invested?

What changes should we pay attention to in the short- to medium-term to understand whether the investment is on track to create longer-term value?

What would enough value look like?

Why and for whom is this investment needed? What is an appropriate and fair distribution of resources, actions, impacts and value?

These questions helped to define program-specific criteria, which were grouped under the 5Es: Economy is concerned with stewardship of resources. Efficiency looks at ways of working including the productivity of organisational actions. Effectiveness focuses on the short, medium and long-term impacts of those actions. Cost-effectiveness considers whether the organisational actions and impacts create enough value to justify the resource use. Equity is relevant at every level.

This process surfaced a long list of considerations. To help prioritise the most important aspects of resource use and value creation to focus on, the team considered one more question:

What critical factors affect whether the investment creates a lot of value or a little?

The resulting five criteria and 21 sub-criteria, developed and validated with stakeholders, are summarised as follows:

Standards

Standards are defined levels of value, providing a transparent basis for making evaluative judgements against each criterion. In this instance, the team adopted the following generic standards from King & OPM (2018).

Together, the value proposition, criteria and standards provided an agreed framework for determining what evidence to gather and analyse (from existing evaluation, research and monitoring data and international literature), and how to interpret the evidence to make judgements about the performance and value of Ka Ora, Ka Ako.

Are free school lunches worth investing in?

According to this analysis, yes. Overall, the evaluation found that Ka Ora, Ka Ako:

is currently performing very well against 21 stakeholder-determined criteria. The major improvements identified are getting secure, ongoing funding for the programme; identifying ways to expand the programme so that all children in Aotearoa New Zealand will benefit; undertaking a formal cost-effectiveness study; and building in more environmental sustainability (Mejia Toro & Swinburn, 2024).

The following table shows preliminary findings against each criterion. These provisional ratings were made by the evaluation team on the basis of the agreed criteria and standards and have yet to be validated with stakeholders. The effectiveness criteria (in red) are the primary outcomes, based on the original Cabinet papers for the program.

To find out more

Preliminary evaluation findings are presented in the following two documents:

Mejia Toro, C., Swinburn, B. (2024). Evidence for free school lunches: Are they worth investing in? Public Health Communication Centre Aotearoa.

Swinburn, B., Mejia Toro, C., King, J., Rees, D., Tipene-Leach, D. (2024). Value for Investment analysis of Ka Ora, Ka Ako. Public Health Communication Centre Aotearoa.

Further detail is presented in the following webinar. The whole webinar is well worth watching to understand the benefits of free school lunches, the negative impacts of hunger on learning, and the processes and content of the VfI evaluation. Prof Swinburn’s VfI presentation starts at 33:52.