Value for Investment in a Youth Primary Care Mental Health initiative

A worked example of the VfI approach in action, from Aotearoa New Zealand

A couple of weeks ago, Adrian Field and I shared a new guide, which introduces Value for Investment (VfI) principles and processes, illustrating their use in a real-world evaluation. This is a follow-up post. It unpacks how the evaluation team, led by Dovetail Consulting, used the VfI approach to provide clear answers to ‘value for money’ questions, in this instance without using economic analysis.

The following summary draws on our recent presentations at the Australian Evaluation Society and UK Evaluation Society conferences (copy of slides here), and the guidance document we prepared for Te Whatu Ora. This post is written from my perspective and doesn’t claim to represent the views of Dovetail Consulting or Te Whatu Ora.

The evaluation

The Youth Primary Mental Health and Addictions (Youth PMHA) initiative was established as part of a program called Access and Choice. It aims to meet the needs of rangatahi (young people) aged 12-24 years who are experiencing mild to moderate levels of mental health and/or addiction needs. You can read more about the Youth PMHA initiative here.

The evaluation addressed three key questions:

How does the Youth PMHA create value?

To what extent does the Youth PMHA provide good value for the resources invested?

How could the Youth PMHA provide more value for the resources invested?

A challenging context to assess value for money

Youth PMHA is a good example of a situation where it would be difficult to apply traditional value for money tools, like cost-benefit analysis or cost-utility analysis. For example:

Early days: The evaluation was conducted during early stages of implementation, while 17 services around the country were getting established, building their workforces, starting to work with young people, innovating, adapting and learning by doing. In this context, value was connected to ways of working and early footprints of change rather than longer-term outcomes (which will still be emerging and should be evaluated at the appropriate time).

No quantitative outcome data: Outcome measures were under development but not yet in use. There is some variety in services being used and it will take time to develop and gain buy-in to a consistent validated outcome tool. Early signs of value creation (health system changes and wellbeing outcomes for young people and their families) were assessed qualitatively.

Co-constructing value: The question of ‘value to whom’ came to the fore when assessing Youth PMHA. Rather than using off-the-shelf measures of value, it was important to conceptualise quality and value from the perspectives of young people, including Māori, Pacific, and others with lived experience of mental health and addictions, who have experienced inequities in mental health and wellbeing.

Value of local flexibility and responsiveness: Services were locally designed and delivered, within a national set of guiding principles. Responsiveness to context was an important aspect of good resource use. The variation between services was also important information that could inform learning and spread of good or promising practice.

In short, this evaluation needed to rigorously determine, on the basis of qualitative evidence and administrative data, whether the initiative was on a pathway to deliver longer-term value, based on critical observable features of early performance that matter to people whose lives are affected by the services, and it needed to capture learning that could enhance future value for the resources invested.

The approach

We used an approach called Value for Investment (VfI), an evaluation system designed to bring clarity to answering value for money questions. VfI is underpinned by four principles, detailed in an earlier post:

Inter-disciplinary (combining theory and practice from evaluation and economics)

Mixed methods (combining quantitative and qualitative evidence)

Evaluative reasoning (interpreting evidence through the lens of explicit criteria)

Participatory (involving those whose lives are affected, giving them a voice in evaluation co-design and sense-making).

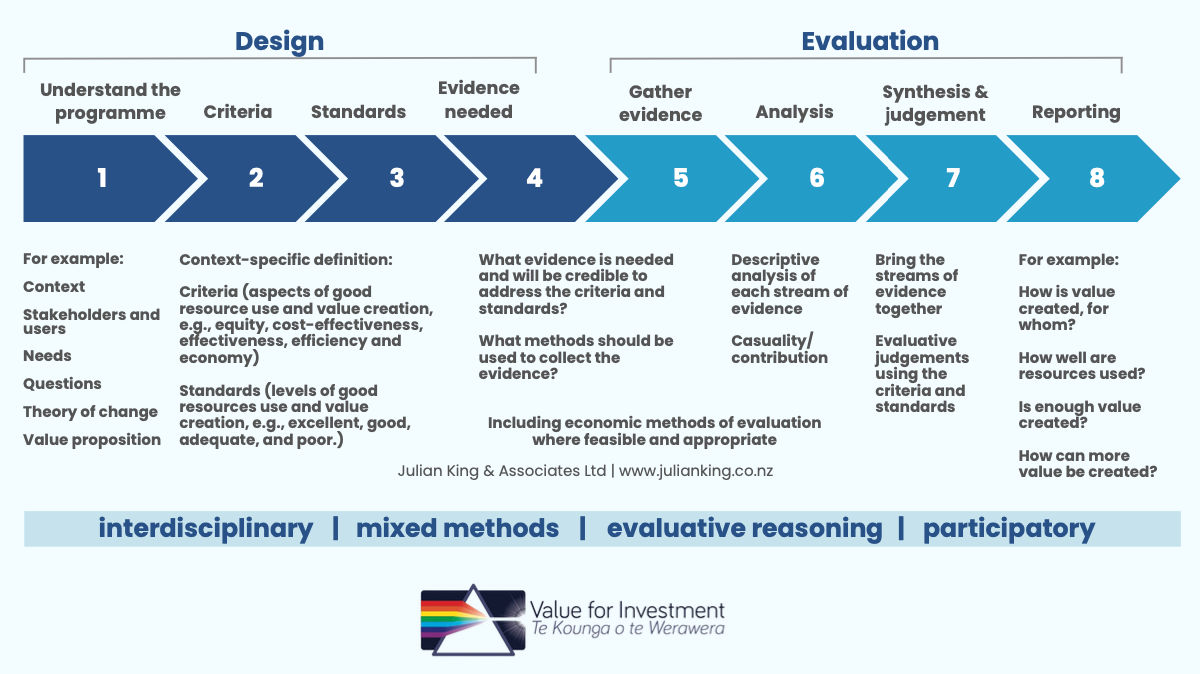

The system is underpinned by a stepped process, summarised in the diagram below. This process makes VfI intuitive to learn, practical to use, and inclusive for people who are not familiar with evaluation.

Stakeholders were involved throughout the process so that the evaluation was informed by their values and lived experiences.

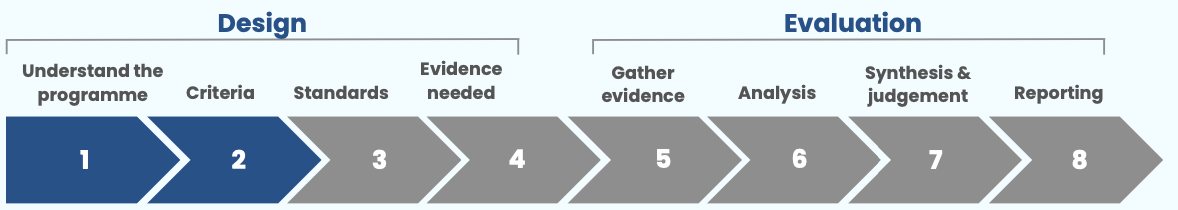

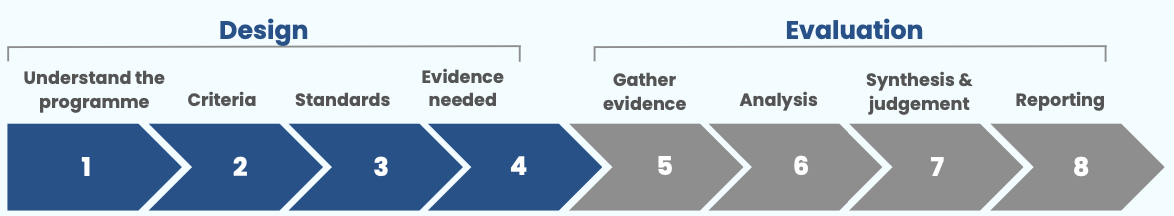

The process includes four design steps (1-4) and four implementation steps (5-8). First, understand the program. Second, develop criteria (aspects of value). The reason we develop criteria second is so that we can align them with the program’s theory and the realities of its context. Third, develop standards (levels of value). We do this third so that we can describe, for each criterion, what the evidence would look like at different levels of value such as excellent, good, or adequate. A matrix of criteria and standards is a rubric - so steps 2 and 3 are the rubric development steps.

Fourth, identify what evidence we need. We do this fourth because rubrics define the focus and scope of the evaluation - so it’s only after we’ve developed rubrics that we can be clear about what evidence is needed and what mix of methods is appropriate. Then we can move to implementing the evaluation: Step 5, gather evidence. Step 6, analyse it. Step 7, synthesise it through the lens of the rubrics. Step 8, communicate findings.

The approach is explicit about distinguishing evaluative reasoning (how we make judgements) from methods (how we gather and analyse evidence). The process is like a sandwich - the reasoning is the bread and butter (steps 2-3 and step 7), and the methods are the filling (steps 4-6).

Following these steps facilitates clear and coherent organisation of key concepts across program theory, rubrics, evidence, judgements, and reporting. Although the steps are characterised as a sequence, a skilled evaluation team in a complex evaluation may iterate between them.

Applying the approach in Youth PMHA

The following sections provide a worked example of each step of the VfI approach, using the Youth PMHA evaluation to illustrate what the VfI process can look like in practice. More detail on what we did at each step is included in the guide.

The example is illustrative; every evaluation is different, and the VfI system encourages evaluators to match methods and tools to context, guided by the principles and the 8-step process.

Evaluation co-design

The first four steps of the VfI process are evaluation design steps: understanding the program, developing criteria and standards, and identifying what evidence is needed. We worked with an advisory group of stakeholders (aka “kaupapa partners”) to address these design steps, resulting in an evaluation framework and plan.

Kaupapa partners included people from the funding agency and young people with lived experience of mental health and/or addiction needs. They came to a series of workshops to share their perspectives on how they thought Youth PMHA should be implemented and what success and value for investment would look like. In these workshops, we facilitated reflection and brainstorming sessions to collaboratively and iteratively design the evaluation.

Here’s a four and a half minute overview of the evaluation design process from the perspective of a key stakeholder, Jane Moloney. This video was part of our presentation at the AES Conference. In it, Jane describes the collaborative approach and nicely sets the scene for the elements of the approach detailed below.

1. Understand the program

In any evaluation it’s a good practice to invest some time in understanding the program and its context. As evaluation consultants we are typically ‘visiting’ a new setting, as outsiders. We need to orient ourselves to the evaluation by asking questions like:

What needs is Youth PMHA intended to meet, and how is it designed to meet them?

Who are the stakeholders, and what’s at stake for them?

Who are the end users of the evaluation, and how will they use it?

What questions does this evaluation need to answer?

For example, one of the early design workshops included developing the three Key Evaluation Questions (KEQs) that guided and structured the evaluation: How does the Youth PMHA create value? To what extent does the Youth PMHA provide good value for the resources invested? How could the Youth PMHA provide more value for the resources invested?

During this step we also worked with kaupapa partners to develop a theory of change. Often in an evaluation, a theory of change is an important point of reference when developing criteria, and there should be a logical coherence between the criteria and the program theory. However, when developing a value for investment framework it can sometimes take a leap of logic to get from a theory of change to a set of criteria describing what good resource use and value creation look like.

To bridge this gap, we added a theory of value creation which sought to elaborate on Youth PMHA processes and outcomes by considering what is valuable about them and what it means in this context to use resources well to create value. The more clearly we can define an initiative’s value proposition, the better-placed we will be to evaluate it.

Developing a theory of value creation involves pondering questions such as:

What is the value proposition of the initiative?

What resources are invested? By whom? (hint: not just money)

What value is created? By whom? For whom?

How is value created (e.g., the activities and mechanisms that create value)

How is value distributed (e.g. the channels through which the initiative works, and who benefits)

What factors might affect the initiative’s ability to create value (e.g. enablers and barriers that determine whether it creates a lot of value or a little value).

A theory of value creation could be part of the theory of change or could be separate. It could be a diagram and/or narrative. In this case we presented the theory of change and theory of value creation side by side, like this:

As you’ll see below, the theory of value creation maps to the criteria that we developed next.

2. Criteria

VfI criteria are the aspects of good resource use that the evaluation focuses on. They can include features of the resource use itself (‘what did we put in?’), consequences of the resource use (‘what did we get out?’) and whether enough value is created to justify the resource use (‘was it worth it?’).

In a VfI evaluation, criteria are contextually determined, in collaboration with stakeholders. In this evaluation, we developed three overarching VfI criteria aligned with the theory of value creation. Under each of the three main headings, we developed sub-criteria which elaborated on the theory of value creation, including definitions of:

Looking after resources equitably and economically including sub-criteria for procurement and funding processes, the initiative’s design and knowledge base, performance management and accountability

Delivering services equitably and efficiently including sub-criteria for equitable and flexible service access, reaching young people and their whānau/family, shifting the locus of control, manaakitanga and cultural fit, system connections, learning and improving

Generating social value equitably and effectively including sub-criteria for wellbeing outcomes for rangatahi and whānau/family, and more efficient and equitable use of health care resources.

You may have noticed that we were riffing off the ‘five Es’ framework, a set of criteria (economy, efficiency, effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and equity) often used in VfM assessments of development programs. But in this case we were putting equity up front at every level, because the purpose of the initiative was fundamentally tied to addressing inequities. ‘Addressing equities efficiently’ is a different objective from simply ‘being efficient’, involving different priorities, strategies, and trade-offs, and the evaluation needed to make this explicit.

3. Standards

VfI standards are defined levels of performance that apply to each criterion. In this evaluation, we developed rubrics (criteria x standards) with four levels of performance:

Excellence

Pathway towards excellence

Meeting minimum requirements

Not meeting requirements.

The rubrics were developed collaboratively, in line with the principles outlined in this earlier post on developing rubrics with stakeholders. Our workshops focused on developing agreed definitions of performance and value at two of the four levels, “meeting minimum requirements” and “excellence”, for all sub-criteria. Having two descriptive levels in the rubric provided enough guidance to make evaluative judgements at four levels, by interpolating. Here’s an example. The full rubric can be seen in the guidance document.

This flexible, developmental framing was important because the standards were set before the service providers were up and running, and because services were working adaptively and in unique ways in each community. An important consideration when developing the rubrics was balancing the need to provide enough guidance to support sound evaluative reasoning while at the same time not over-specifying aspects that are not knowable in advance.

4. Evidence needed

Once the rubrics were developed, we had a clear picture of what the evaluation would focus on and how judgements would be made. The rubrics helped us to determine what kinds of evidence would be needed and credible to address the criteria and standards, and what design and mix of methods should be used.

Evidence used in an evaluation doesn’t necessarily have to be new evidence; in this case, we were able to draw on existing program management reports and administrative data, as well as collecting new evidence. The mix of evidence sources and methods was agreed in discussion with kaupapa partners and included:

Interviews with young people, service providers and the funding agency

Surveys of young people and service providers

Analysis of program documents such as providers’ narrative progress reports

Analysis of service data covering service user demographics, individual and group sessions provided, waiting times, inter-service referrals, and workforce statistics.

Where feasible and appropriate, VfI often includes economic methods of evaluation such as cost-benefit or cost-effectiveness analysis. These methods can contribute important insights. In this evaluation, however, economic evaluation was agreed to be out of scope because the kinds of evidence that would have been needed to undertake a high quality economic analysis were not available at the time of the evaluation. The VfI system, in this instance, provided a viable alternative.

At the end of the evaluation design phase, we prepared a written evaluation framework and plan. This is an important step: once the document is endorsed by the funding agency and stakeholders, we can proceed to implementing the evaluation.

Implementing the evaluation

Implementing the evaluation involves: gathering and analysing evidence; bringing the streams of evidence together, guided by the rubrics, to synthesise and make evaluative judgements; and reporting findings.

5. Gather evidence

Gathering the necessary evidence involved following good practices and ethical standards associated with interviewing, surveys, documents and administrative data analysis. The evaluation team included young people and Māori team members with a view to ensuring a good cultural fit between interviewers and interviewees.

The rubrics provided a ready organising structure to support data collection. In Youth PMHA, we designed our interview guides and surveys to map to the criteria and sub-criteria, making the evidence efficient to analyse. As you’ll see in the diagram and the subsequent steps outlined below, the theory of value creation and VfI criteria provided structure for each step of the evaluation including evidence gathering, analysis, synthesis, and reporting.

6. Analysis

In the analysis step, each stream of evidence is analysed individually to identify findings that are relevant to the evaluation questions, criteria and standards. Each strand of evidence may be analysed by different team members. In this evaluation, different team members took responsibility for analysing and writing up evidence from different sources, producing a series of annexes for the evaluation report.

If you take a look at the annexes in the report, you’ll see how the structure of each annex maps back to the rubrics, with a consistent structure of headings and sub-headings systematically addressing applicable criteria and sub-criteria.

In any evaluation, it’s important to address the question of causality. Here, we considered the contribution of Youth PMHA to the changes identified through stakeholder feedback, using the theory of change for guiding structure to consider whether there were sufficient rationale to convince a reasonable but sceptical observer that the results were consistent with Youth PMHA contributing to reported changes for young people and their families.

7. Synthesis and judgements

Synthesis is a distinct and separate step from analysis. Whereas analysis involves examining pieces of evidence separately, synthesis involves combining all the elements to make sense of the totality of the evidence collected. This is also the step at which we make evaluative judgements using the rubrics.

To keep the synthesis process well organised across quite a large team, we developed a standardised reflection template for collating evidence to address each sub-criterion systematically. These reflection templates were structured to map back to the rubrics. This helped team members to reflect on the evidence in preparation for shared sense-making processes. They provided a consistent structure across the team and helped identify issues for collective team deliberation during the synthesis step.

We held sense-making sessions with the evaluation team to consider the full qualitative and quantitative findings and tentative evaluative judgements.

After that, we presented draft evaluation findings in a workshop with stakeholders, providing the opportunity to validate, contextualise and challenge our preliminary findings, and to share their perspectives about the implications of the findings for generating future value.

Stakeholder engagement is important during this step, because a collaborative sense-making process contributes to evaluation validity by incorporating multiple perspectives. It also promotes stakeholders’ understanding, ownership and use of the findings. Here’s an earlier post on sense-making with stakeholders and rubrics.

This type of inclusive process can be applied without compromising the independence of the evaluation; the evaluation team remained responsible for the final evaluative judgements.

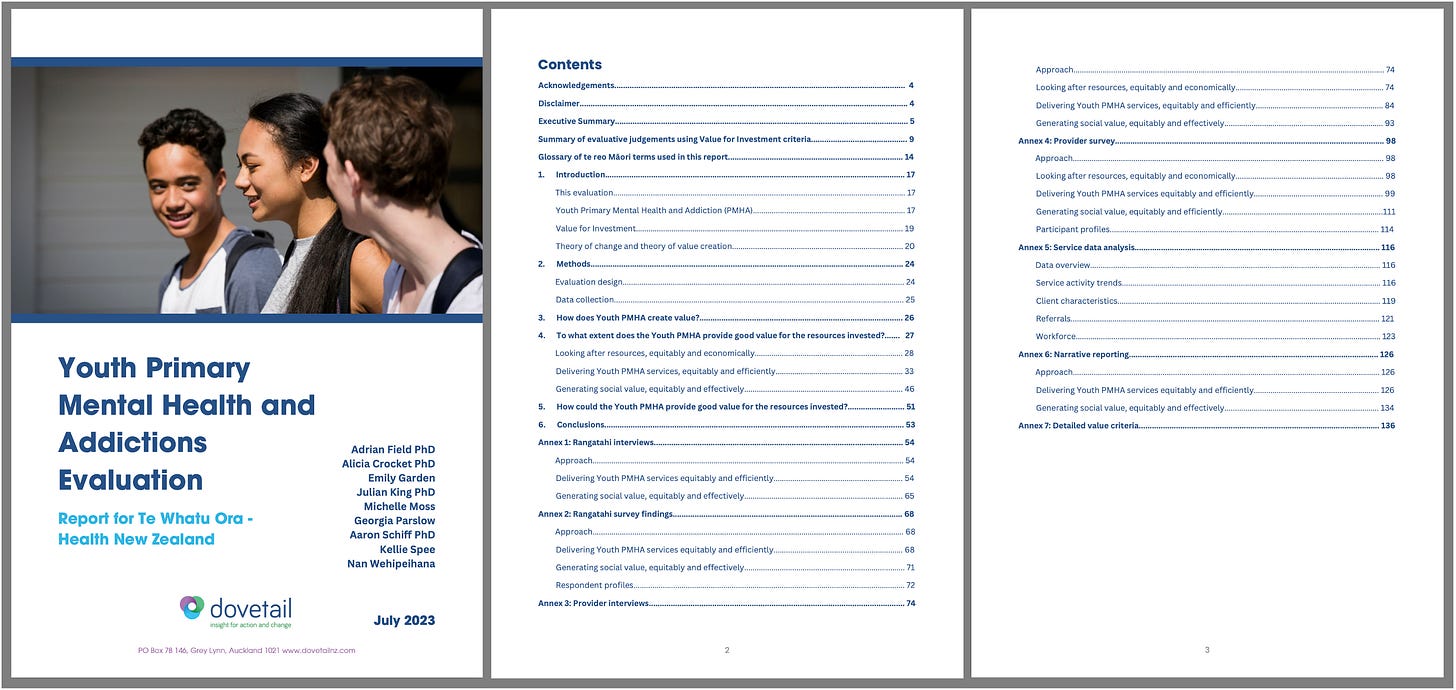

8. Reporting

A good evaluation report gets straight to the point and gives a clear statement of findings, including evaluative judgements. The reader should not have to work hard to find answers to the KEQs. And a good report makes the evaluative reasoning explicit, showing how judgements were made from the evidence.

The Youth PMHA evaluation is a case in point. It provides an Executive Summary in four pages, which succinctly answers each of the three KEQs in turn. Directly after the Executive Summary is a table that systematically presents VfI ratings against each criterion, together with key evidence supporting the ratings. For example:

The subsequent three sections of the report provide more detailed findings for each KEQ in turn – using the criteria as sub-headings within each section and weaving key pieces of mixed methods evidence together to systematically address each criterion.

The main body of the report is relatively compact at 36 pages, while the annexes provide deeper analysis of evidence from each source. This approach to reporting ensures the most important information for decision-makers is presented as early as possible in the report, and that sufficient evidence and reasoning are presented, in a logical manner, to show how conclusions were reached. The transparency of this approach means that the judgements are traceable and challengeable, supporting evaluation credibility and validity.

Links to further information

The new open-access guide is available here. It describes the principles and processes underpinning the VfI system, using the Youth PMHA example to illustrate what they look like in action.

For a reflection on insights gained from the use of the VfI system in this evaluation, see our earlier post.

You can also read a summary of the Youth PMHA evaluation on the Dovetail Consulting website here and download the full evaluation report here.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to all participants in this evaluation, including the young people, whānau, and staff of service providers and Te Whatu Ora who participated and offered their time, thoughts and reflections. Your critical input to this research is gratefully received. Tuku mihi ki a koutou katoa.

Thanks to the Evaluation Advisory Group of Lia Apperley, Sam Austin, Issy Freeman, Bridget Madar, Jane Moloney and Emma Williams for your guidance and reflection. We also wish to acknowledge Roy de Groot for provision of data for analysis.

This Value for Investment evaluation was funded by Te Whatu Ora – Health New Zealand. It was undertaken by a Dovetail Consulting-led team comprising Dr Adrian Field, Dr Alicia Crocket, Emily Garden, Michelle Moss, Georgia Parslow, Dr Aaron Schiff, Kellie Spee, Nan Wehipeihana and Dr Julian King. Aneta Cram and Victoria King worked with the evaluation team in conducting rangatahi interviews. Dr Uvonne Callan-Bartkiw provided psychological response support to the team and internal peer review.

Need wellbeing support?

If you or someone you know needs wellbeing support in New Zealand, you can find out about the services offered through the Access and Choice programme here.

See also: